The plot is the backbone of any compelling story, the sequence of events that whisks readers from the first page to the satisfying conclusion. From ancient epics to contemporary novels, the art of plot construction has been refined and reimagined across genres and literary traditions. Understanding the architecture of plot, its fundamental components, and the diverse structures it can take is essential for any storyteller seeking to breathe life into their narratives.

But what exactly is in a plot? How does it differ from the broader story? What tools can writers employ to craft plots that surprise and engage? And how does plot intertwine with the very essence of a story?

This article delves deep into the anatomy of plot, exploring its core elements, examining various plot structures that writers can utilize, and uncovering the myriad possibilities of narrative organization.

Let’s begin by defining plot and distinguishing it from the overarching story it serves.

Plot Definition: Unveiling the Core of Narrative

The plot of a story is best understood as the carefully arranged sequence of events that drive a narrative forward. It’s not simply a chronological recounting of what happens; rather, it’s a chain of events where each action is causally linked, influencing and shaping subsequent events. In essence, a story plot is a series of cause-and-effect relationships that build the narrative as a cohesive whole.

What is plot?: A series of interconnected events, driven by cause and effect, that form the structure of a story.

It’s crucial to distinguish plot from a mere story summary. Plot demands causation. The renowned novelist E.M. Forster eloquently captured this distinction:

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.” ― E.M. Forster

The addition of “of grief” transforms a simple sequence of events into a plot by introducing causality. Without it, the queen’s death could be attributed to any number of unrelated reasons. Grief, therefore, not only provides plot structure but also hints at deeper thematic layers within the narrative.

Essential Ingredients: Elements of Plot

A plot isn’t just a random string of occurrences; it’s a purposeful construction built upon essential elements:

- Causation: This is the linchpin of plot. Each event must logically stem from a preceding event, creating a chain reaction that propels the narrative. This cause-and-effect relationship is what gives plot its dynamic energy.

- Characters: Stories are fundamentally human (or character-centric, even with non-human characters). A plot must introduce the key players, the individuals whose actions and decisions drive the events forward. Without characters, there is no agency, no motivation, and consequently, no plot.

- Conflict: Conflict is the engine of plot. It arises from opposing forces, whether they are characters with conflicting desires, internal struggles within a character, or external obstacles. Conflict generates tension, raises stakes, and creates the need for resolution, making it indispensable to plot development.

These elements, when skillfully interwoven, form the very fabric of story structure. Let’s now explore some common plot structures that writers employ to organize these elements effectively.

Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot. ― Leigh Brackett

Navigating Narrative Landscapes: Common Plot Structures

Storytellers throughout history have experimented with diverse plot structures to craft engaging narratives. Understanding these structures can provide a valuable framework for writers, offering solutions to common storytelling challenges and inspiring innovative approaches to plot development.

The Foundational Triangle: Aristotle’s Story Structure

The earliest formal discussion of plot structure can be traced back to Aristotle’s Poetics (circa 335 B.C.). Aristotle conceptualized plot as a narrative triangle, proposing that stories typically unfold in a linear fashion, resolving conflicts in three distinct acts: a beginning, a middle, and an end.

For Aristotle, the beginning should be self-contained, existing independently of prior events and immediately immersing the reader without prompting questions of “why?” or “how?”. The middle should logically extend from the beginning, amplifying the story’s conflicts and complexities. Finally, the end should provide a clear resolution, leaving no loose threads or lingering questions.

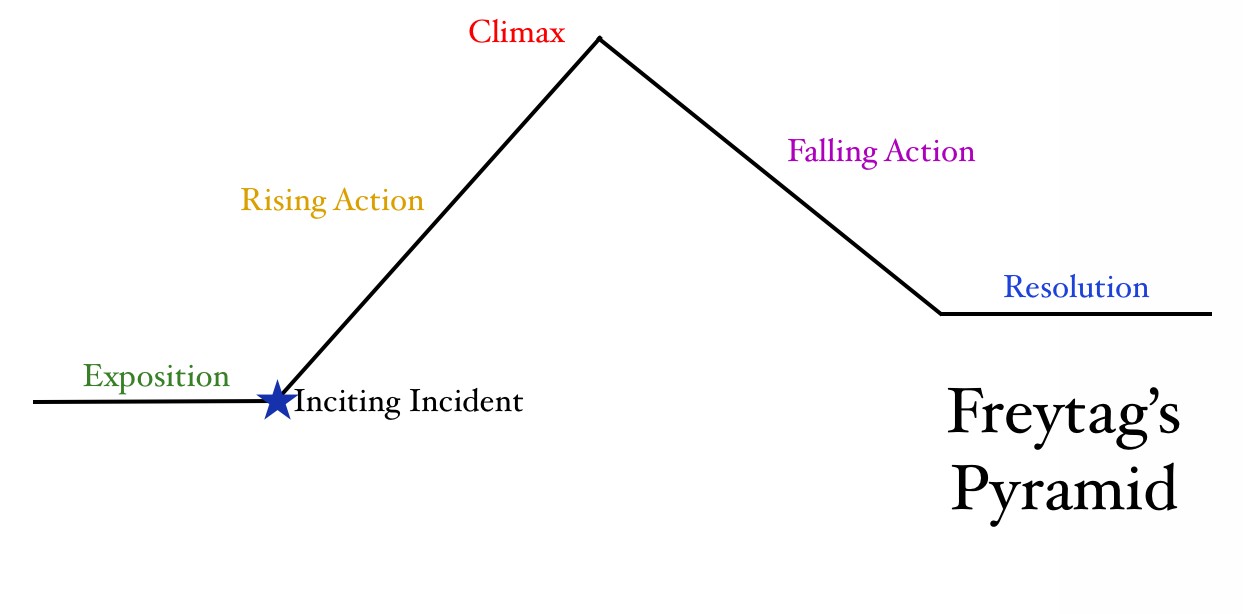

While Aristotle’s model provides a basic blueprint, many stories deviate from this simplicity. Freytag’s Pyramid builds upon Aristotle’s foundation by offering a more nuanced and detailed structural framework.

Expanding the Framework: Freytag’s Pyramid

Freytag’s Pyramid, developed by Gustav Freytag in the 19th century, expands Aristotle’s three-part structure into five key stages, providing a more granular view of plot development:

- Exposition: This is the story’s opening act, where the writer introduces the main characters, establishes the setting, hints at underlying themes, and sets the narrative tone. It lays the groundwork for the unfolding drama.

- Rising Action: Triggered by the inciting incident—the event that sets the story’s central conflict in motion—the rising action is characterized by escalating tension and a series of cause-and-effect events. The conflict intensifies, and the protagonist faces increasing challenges.

- Climax: The pinnacle of the story, the climax is the moment of highest tension where the central conflict reaches its peak. It’s the turning point where the protagonist’s fate is often decided.

- Falling Action: Following the climax, the falling action depicts the immediate consequences and reactions to the climactic events. Characters grapple with the aftermath, and the intensity begins to subside.

- Denouement: The resolution of the story, the denouement (or resolution) ties up loose ends and provides a sense of closure. It may offer a clear resolution or leave the reader with lingering questions, depending on the narrative intent.

For a deeper dive into Freytag’s Pyramid, further resources are readily available online.

The 8-Point Arc: Nigel Watts’ Narrative Progression

Building upon Freytag’s Pyramid, Nigel Watts proposed the 8-Point Arc, a more detailed model that outlines eight essential plot points that contribute to a complete narrative:

- Stasis: The story begins with the protagonist in their ordinary, everyday life, a state of relative equilibrium that is soon to be disrupted.

- Trigger: An event beyond the protagonist’s control acts as the inciting incident, disrupting the stasis and initiating the story’s central conflict.

- The Quest: Analogous to the rising action, the quest represents the protagonist’s journey and efforts to confront and resolve the conflict.

- Surprise: Unexpected twists, turns, and revelations emerge during the quest, complicating the protagonist’s path and adding layers of intrigue. These surprises can be obstacles, setbacks, or internal realizations.

- Critical Choice: The protagonist faces a pivotal, life-altering decision. This choice reveals their true character and dramatically impacts the subsequent events of the story.

- Climax: The direct consequence of the critical choice, the climax is the peak of tension, where the outcome of the protagonist’s decision is revealed.

- Reversal: The protagonist experiences a significant shift in fortune or status as a result of the climax. This reversal can be positive or negative, affecting their social standing, worldview, or even their life.

- Resolution: The story concludes with a return to a new state of stasis, a changed reality shaped by the events of the narrative. This new equilibrium reflects the protagonist’s transformation and the resolution of the central conflict.

By ensuring that a plot progresses through these eight points in sequence, writers can construct a well-rounded and satisfying narrative arc.

Watts elaborates on this structure in his book Write a Novel and Get It Published.

Save the Cat: A Screenwriter’s Blueprint

Developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder, the Save the Cat plot structure, while originally conceived for screenplays, provides a highly detailed and adaptable framework applicable to various forms of storytelling.

Rather than replicating the detailed breakdown here, resources like Reedsy offer comprehensive guides and worksheets for understanding and applying the Save the Cat structure to your own writing.

The Hero’s Journey: Mythic Structure of Transformation

The Hero’s Journey, popularized by Joseph Campbell, proposes a universal plot structure found in myths and stories across cultures. Campbell identified three primary acts in this journey, representing the transformative stages a hero undergoes:

Act 1: The Departure: The hero leaves their ordinary world, venturing into the unknown.

Act 2: The Initiation: The hero faces trials, encounters allies and enemies, and undergoes a period of transformation in the unfamiliar world.

Act 3: The Return: The hero, now changed, returns to their original world, often bringing a boon or elixir that benefits their community.

Christopher Vogler, in The Writer’s Journey, expands upon Campbell’s three acts, outlining a 12-step process that provides a more granular roadmap for the Hero’s Journey:

The Departure Act:

- The Ordinary World: The hero is introduced in their everyday setting, providing a baseline before the adventure begins.

- The Call to Adventure: A challenge or opportunity arises, beckoning the hero to leave their ordinary world and embark on a journey.

- Refusal of the Call: Initially hesitant or fearful, the hero may resist the call to adventure, recognizing the potential dangers and uncertainties.

- Meeting the Mentor: A wise and experienced mentor figure appears to guide and encourage the hero, providing support and wisdom to overcome their initial reluctance and prepare for the journey.

The Initiation Act:

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero commits to the adventure and enters the unfamiliar world, crossing a point of no return and leaving their ordinary world behind.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero encounters challenges, forms alliances, and confronts adversaries in the new world, learning and growing through these interactions.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: The hero nears the heart of the adventure, the most dangerous and challenging location, requiring preparation and strategic planning.

- Ordeal: The hero faces their greatest trial to date, a moment of intense crisis that tests their limits and forces them to confront their deepest fears. This is often a low point in the hero’s journey.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): Having survived the ordeal, the hero gains a reward, which could be a physical object, knowledge, or a newfound understanding, empowering them for the next stage of the journey.

The Return Act:

- The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, but the return is not without its own challenges and dangers.

- Resurrection: The hero faces a final, decisive confrontation, often with a resurrected antagonist or a symbolic representation of their inner demons. This is the ultimate test of their transformation and growth.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to their ordinary world, transformed by their experiences and bearing the “elixir”—a treasure, wisdom, or ability that benefits their community or world.

The Hero’s Journey: A cyclical plot structure representing the stages of a hero’s transformative adventure, from the ordinary world to the triumphant return.

Fichtean Curve: Escalating Action and Climax

The Fichtean Curve, articulated by John Gardner in The Art of Fiction, is particularly well-suited for pulp fiction and mystery stories, though its principles can be applied across genres. This structure emphasizes a rising action that dominates the narrative, leading to a singular climax followed by a brief falling action.

In the Fichtean Curve, the rising action constitutes approximately two-thirds of the story’s length. Crucially, this rising action is not a linear ascent but rather a series of escalating and de-escalating conflicts that progressively build tension towards the climax.

Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Orient Express exemplifies the Fichtean Curve. Hercule Poirot meticulously investigates each suspect, uncovering flaws and secrets, each revelation adding another layer of conflict and suspense, steadily narrowing down the possibilities until the dramatic climax reveals the collective guilt of the passengers.

Conflict: The Indispensable Engine of Plot

Before exploring plot devices, it’s essential to address the role of conflict in plot. Is conflict always necessary? What happens to plot in its absence?

Conflict, in narrative terms, encompasses the opposing forces that impede a character’s goals and desires. This conflict can manifest externally—as antagonists, societal structures, or external obstacles—or internally—as a character’s inner struggles, flaws, or psychological barriers.

Conflict is often considered the driving force of plot. It instigates the inciting incident, fuels the rising action, culminates in the climax, and is ultimately resolved (or not) in the denouement. Plot relies on conflict to maintain reader engagement and propel the narrative forward.

If you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict.

When plot progression stalls, revisiting and intensifying the story’s central conflict can often reignite momentum and provide new directions for the narrative.

It’s important to note that the centrality of conflict in plot is largely a Western narrative tradition. Eastern storytelling structures, such as Kishōtenketsu, may prioritize character development and reactions to external situations over conflict-driven narratives. While conflict may be present, the focus shifts to character complexity and navigating a world beyond their control.

For a more in-depth exploration of conflict in plot, resources like “What is Conflict in a Story? Definition and Examples” offer further insights.

Tools of the Trade: Common Plot Devices

Plot devices are techniques that writers employ to shape and manipulate plot, keeping stories engaging, surprising, and thematically rich. While plot structures provide the framework, plot devices are the tools that bring that framework to life.

Aristotle’s Trio: Essential Plot Devices

Aristotle, in Poetics, identified three plot devices he considered fundamental to effective storytelling:

1. Anagnorisis (Recognition)

“Luke, I am your father!” Anagnorisis is the moment of crucial realization, when the protagonist transitions from ignorance to knowledge. Often occurring near the climax, anagnorisis is the pivotal piece of information that empowers the protagonist to resolve the central conflict.

2. Pathos (Suffering)

Aristotle defined pathos as “a destructive or painful action,” encompassing physical pain, such as death or injury, as well as emotional and existential suffering. He argued that stories often confront extreme pain, and this confrontation is vital for plot progression and emotional impact. (Note: This is distinct from the rhetorical device of pathos, which aims to evoke audience emotions.)

3. Peripeteia (Reversal)

Peripeteia signifies a sudden reversal of fortune, a shift from good to bad or bad to good. Often intertwined with anagnorisis, peripeteia frequently arises from the climax, determining whether the story concludes in triumph or tragedy.

Plot Devices for Structuring Narrative

These devices are particularly useful for shaping the overall structure and flow of a story:

Backstory

Backstory refers to events that precede the main narrative, occurring before the exposition. While backstory can sometimes alter the immediate course of the story, it more often serves to provide context, establish character motivations, and create thematic resonance. Flashbacks are a common technique for revealing backstory within the narrative.

Deus Ex Machina

Deus ex machina, meaning “god from the machine,” is a plot device where a seemingly insurmountable problem is resolved by an unexpected and improbable intervention, often from an external source beyond the protagonist’s control. While sometimes criticized as a convenient or contrived resolution, deus ex machina can be effective in certain genres, particularly comedy or absurdism, or when used ironically.

In Media Res

From the Latin phrase “in the midst of things,” in media res describes a narrative that begins abruptly in the middle of the action, plunging the reader directly into the story without extensive exposition. This technique can create immediate intrigue and suspense, drawing the reader in to piece together the context as the story unfolds.

Plot Voucher

A plot voucher is an element introduced early in the story that seems insignificant at the time but becomes crucial later in the plot. This “voucher” might be an object, a piece of information, or an alliance with another character. The Resurrection Stone hidden within Harry Potter’s first Golden Snitch serves as a plot voucher, its significance revealed much later in the series.

Plot Devices for Heightening Tension

These devices are designed to create suspense, mystery, and reader engagement:

Cliffhanger

A cliffhanger occurs when a story ends abruptly at a moment of high tension, typically just before the climax is resolved. This leaves the reader in suspense, eager to know the outcome. Cliffhangers are commonly used in serialized narratives but can also be employed for literary effect, as seen in One Thousand and One Nights, where Scheherazade uses cliffhangers to prolong her life.

MacGuffin

A MacGuffin is a plot device where an object, event, or goal drives the plot forward, but its intrinsic value is secondary or even nonexistent. The protagonist’s desire for the MacGuffin sets the plot in motion, but the MacGuffin itself is often less important than the journey and the lessons learned. The falcon statuette in The Maltese Falcon is a classic MacGuffin; its actual value is irrelevant to the intricate web of intrigue it sets in motion.

Red Herring

A red herring is a deliberate distraction, misleading the reader (or characters) with seemingly relevant but ultimately false clues or information. Primarily used in mystery and suspense genres, red herrings create misdirection and heighten suspense. While effective in creating twists and turns, overuse of red herrings can risk frustrating or alienating the reader. (This is distinct from the logical fallacy “red herring,” which is an irrelevant argument used to distract from a flawed premise.)

For a broader exploration of plot devices and storytelling techniques, resources like “The Art of Storytelling” offer further insights.

Archetypal Narratives: 8 Types of Plot in Literature

Certain plot patterns recur throughout literature, particularly in genre fiction. These archetypal plots build upon the plot devices discussed earlier and often feature familiar tropes and character archetypes.

While not all of these plot types were originally defined by Christopher Booker in The Seven Basic Plots (some less common plots have been omitted), they represent frequently encountered narrative structures:

1. Quest

The Quest plot is characterized by a protagonist embarking on a journey from their home in search of something specific—treasure, love, truth, a new home, or a solution to a problem. Often accompanied by companions and initially hesitant, the protagonist undergoes significant transformation during the quest, returning home wiser, stronger, and irrevocably changed (if they survive).

Examples: The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, the Harry Potter series.

2. Tragedy

Tragedy centers on a well-intentioned protagonist who, due to inherent flaws (hamartia) or unfortunate circumstances, fails to overcome the central conflict. Tragedies often explore themes of fate, free will, and the limitations of human nature. Readers connect with tragic heroes despite (and sometimes because of) their flaws, and their downfall often evokes a sense of profound loss.

Examples: Romeo & Juliet by William Shakespeare, The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald, Oedipus Rex by Sophocles, Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, Of Mice and Men by John Steinbeck, Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë.

3. Rags to Riches

Rags to Riches narratives chart the protagonist’s journey from poverty to wealth. These stories often explore themes of social class, identity, and the transformative power of wealth. The plot typically focuses on the protagonist’s adaptation to their new circumstances and their evolving relationship with wealth.

Examples: Great Expectations by Charles Dickens, The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas, Q & A by Vikas Swarup.

4. Story Within a Story (Embedded Narrative)

The Story Within a Story, or embedded narrative, is a less structured plot type where a secondary story is interwoven into the main narrative. This embedded story, with its own plot and conflict, serves to amplify or comment on the themes of the primary narrative. It should not be confused with parallel plot, as the embedded story is subservient to the main plot.

Examples: The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoevsky, Hamlet by William Shakespeare, Moby-Dick by Herman Melville, Afterworlds by Scott Westerfeld, Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes.

5. Parallel Plot

Parallel Plot stories feature two or more distinct storylines unfolding simultaneously. These plots are interconnected, influencing each other thematically or through shared characters or events, with each narrative thread holding equal importance to the overall story.

Examples: Kafka on the Shore by Haruki Murakami, A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens, Break the Bodies, Haunt the Bones by Micah Dean Hicks, The Testaments by Margaret Atwood, In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez.

6. Rebellion Against “The One”

Rebellion narratives depict a protagonist who actively resists an oppressive, all-powerful antagonist (“The One”). Despite their efforts, the protagonist, often outmatched and isolated, may ultimately fail to overthrow the antagonist, leading to submission or even death.

Examples: 1984 by George Orwell, The Hunger Games series by Suzanne Collins, “Harrison Bergeron” by Kurt Vonnegut, The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood.

7. Anticlimax

Anticlimax plots deviate from conventional structure by focusing on the falling action after a major climax that has already occurred (often off-page or in backstory). The narrative explores the aftermath and consequences of this prior climax, rather than building towards a new one. This is distinct from the plot device of anticlimax, which refers to a disappointing or underwhelming resolution.

Examples: The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner, Encircling by Carl Frode Tiller, Oryx & Crake by Margaret Atwood.

8. Voyage and Return

Voyage and Return stories involve protagonists who journey to unfamiliar worlds and then return home, transformed by their experiences. While often overlapping with the Quest plot, Voyage and Return narratives emphasize the contrast between the familiar and the unfamiliar, and the protagonist’s adaptation to both. The return journey and the protagonist’s reintegration into their original world are key elements.

Examples: The Iliad and the Odyssey by Homer, Coraline by Neil Gaiman, The Lord of the Flies by William Golding, Gulliver’s Travels by Jonathan Swift, Candide by Voltaire, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by L. Frank Baum.

Plot-Driven vs. Character-Driven Narratives

A common distinction in fiction categorizes stories as either “plot-driven” or “character-driven.” This distinction highlights the primary engine of the narrative: is the plot shaping the characters, or are the characters’ actions and motivations driving the plot?

This distinction is often used to differentiate between literary fiction and genre fiction. Literary fiction often prioritizes character development and psychological depth, with plot emerging organically from character decisions and internal conflicts. Genre fiction, on the other hand, often adheres to established plot structures and tropes, with characters sometimes serving to fulfill plot requirements.

However, this distinction is not absolute. Literary fiction can utilize genre plot devices, and genre fiction can be deeply character-driven. Effective storytelling often involves a dynamic interplay between plot and character, where each element enriches and informs the other.

Your story should build a working relationship between the characters and the plot, as both are essential elements of the storyteller’s toolkit.

Plot vs. Story: Defining the Nuances

Finally, let’s clarify the distinction between plot and story. While often used interchangeably, these terms have distinct, though related, meanings.

Plot Definition: The sequence of events in a story, emphasizing cause and effect. Plot answers the What, When, and Where of the narrative. It is the structural framework upon which the story is built.

Story Definition: The complete narrative, encompassing plot, characters, themes, and underlying meaning. Story answers the Who, Why, and How of the narrative. It is the full, immersive experience that the writer creates for the reader.

For a deeper understanding of crafting compelling stories from well-developed plots, explore resources like “Stories vs. Situations: How to Know Your Story Will Work in Any Genre.”

Mastering Plot at Writers.com

Storytellers approach plot creation in diverse ways. “Pantsers” write organically, making plot decisions as they go, while “plotters” meticulously outline every plot point in advance.

Whether you are a pantser, a plotter, or somewhere in between, Writers.com offers resources to enhance your storytelling skills. Explore courses like Plot Your Novel or delve into various writing aspects in their upcoming writing classes.