“The word ‘love’ is most often defined as a noun, yet all the more astute theorists of love acknowledge that we would all love better if we used it as a verb.” —bell hooks, All About Love

This powerful quote by bell hooks sets the stage for a deeper exploration into the essence of verbs. Often confined to grammar textbooks, verbs are so much more than just words that describe actions. They are the driving force of language, and perhaps, life itself. But What Are Verbs truly, beyond their grammatical definition? Let’s delve into this question and discover why understanding verbs in a broader sense can be transformative.

Verbs, in their most basic sense, are the engine of sentences. They are the words that express action, occurrence, or state of being. Think of words like run, jump, think, exist, become. These are all verbs, and they give sentences their dynamism and meaning. Without verbs, language would be static, a mere collection of nouns and adjectives, lacking the vital element of motion and existence.

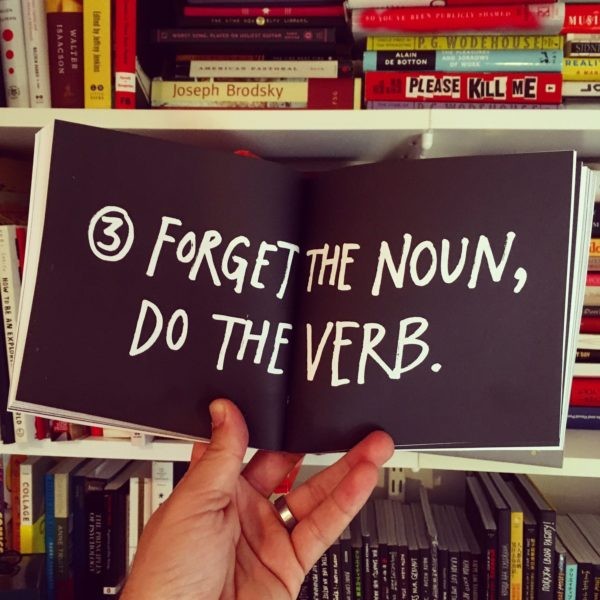

But the significance of verbs extends far beyond grammar. In his book Keep Going, Austin Kleon encapsulates this broader meaning in a chapter titled, “Forget the noun, do the verb.” This simple yet profound statement encourages us to shift our focus from static identities (nouns) to dynamic actions (verbs). This concept resonates deeply with thinkers and creators across various fields.

Stephen Fry, in a 2010 interview, eloquently articulated this idea when speaking to a young interviewer. He warned against the limiting nature of nouns, suggesting that defining oneself by a single noun – “an actor,” “a writer” – can be imprisoning. Fry stated, “We are not nouns, we are verbs. I am not a thing – an actor, a writer – I am a person who does things – I write, I act – and I never know what I am going to do next. I think you can be imprisoned if you think of yourself as a noun.” This perspective encourages us to embrace a fluid identity, defined not by labels but by the actions we undertake. It’s about focusing on doing rather than being in a fixed sense.

This philosophy is further echoed in R. Buckminster Fuller’s work, most notably in the title of his book, I Seem To Be A Verb. Fuller, a visionary thinker and inventor, saw himself not as a static entity but as a continuous process of action and engagement with the world. His very being was defined by his contributions, his creations, his doing. This title encapsulates the idea that life is not a state of being but a state of becoming, constantly shaped by our verbs – our actions.

Karen Armstrong, in her essay “What Atheists Can Learn from Believers,” offers another compelling perspective on verbs, this time in the context of religion. She emphasizes that historically, religion was primarily a verb, a practice, a set of actions, rather than a set of beliefs. Armstrong points out that the modern Western world often prioritizes belief over action, turning faith into an intellectual exercise. However, she argues that true faith, in its original sense, is about commitment and practice. “Usually religion is about doing things and it is hard work,” she writes. This “doing” aspect of religion, the practical discipline and commitment, is where the real understanding and meaning emerge. She quotes Saint Anselm, “Credo ut intellegam – I commit myself in order that I may understand,” highlighting that understanding comes through action and commitment, through doing the verb of faith.

Armstrong draws a parallel between religious practice and understanding. She asserts, “If you don’t do religion, you don’t get it.” Religion, in this sense, becomes a “practical discipline in which we learn new capacities of mind and heart.” This concept can be readily applied to creativity and art. Many aspiring artists believe they must first identify as an “artist” (noun) before they can begin creating art. However, the reality is often the reverse.

As writer Mary Karr eloquently puts it when discussing her own faith, “It’s a practice. It’s not something you believe. It’s not doctrine. Doctrine has nothing to do with it. It’s a set of actions.” Karr emphasizes the experiential nature of faith, highlighting that it is through the actions, the practices, that one truly engages with and understands faith, just as with any craft or discipline. Her advice is simple yet profound: “Why don’t you just pray for 30 days and see if your life gets better?” This is an invitation to do the verb, to engage in the practice, and to discover the understanding and benefits through action itself.

Therefore, when we ask, “what are verbs?”, the answer transcends grammatical definitions. Verbs are about action, practice, commitment, and dynamism. They are about defining ourselves not by static labels but by the continuous flow of our actions. Forget rigidly defining yourself as a noun; instead, embrace the power of verbs. Start doing. Start creating. Start living actively. The understanding of who you are and what you are meant to be will emerge from the verbs you choose to enact. Embrace the verb – and watch your world, and your understanding of yourself, unfold.