Emerson Romero, a name perhaps not widely known, yet incredibly significant in the history of film accessibility for the deaf and hard of hearing. Born on August 19, 1900, and passing away on October 16, 1972, Romero, also known by his stage name Tommy Albert, was more than just a silent film actor. He was a visionary who pioneered techniques that laid the groundwork for modern movie captioning. While his life’s work is well-documented and celebrated, the specific details surrounding what Emerson Romero died from remain less discussed. This article aims to explore his remarkable contributions and shed light on his passing, within the context of his impactful life.

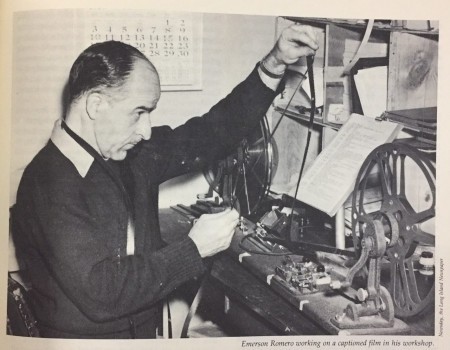

Emerson Romero checking 16mm film frames against a caption list, highlighting his pioneering work in captioned films for the deaf.

Emerson Romero checking 16mm film frames against a caption list, highlighting his pioneering work in captioned films for the deaf.

Romero’s journey began in the world of silent films in the 1920s. Under the moniker Tommy Albert, he graced the silver screen in over two dozen two-reel comedies between 1926 and 1928. Titles like Beachnuts and The Cat’s Meow showcase his foray into slapstick and physical comedy, common in the silent era. He even shared sets with legendary figures like W.C. Fields, undertaking his own makeup and stunts, demonstrating a hands-on approach to filmmaking. The transition to “talkies” in 1927, however, dramatically altered the landscape for deaf actors and audiences alike. The disappearance of intertitles meant films became inaccessible to the deaf community, effectively silencing their cinematic experience.

This shift spurred Romero into action. Deeply involved in New York City’s deaf community, he co-founded the Theatre Guild of the Deaf in 1934 with John Funk and Sam Block. For two decades, this theater company thrived, providing Romero a platform to act and direct, keeping the performing arts alive within the deaf community. But Romero’s ambition extended beyond the stage. He sought to bring movies back to deaf audiences.

In 1947, Romero embarked on a groundbreaking experiment: captioning sound films. His method, though rudimentary by today’s standards, was revolutionary. He physically cut film strips and inserted frames with captions between the picture frames. This innovative, albeit visually imperfect, technique effectively created subtitles, reminiscent of the intertitles from the silent film era. He rented these captioned films to deaf schools and clubs, making cinema accessible once again. Although the visual quality was compromised, and the soundtrack was unfortunately destroyed for hearing viewers, Romero’s pioneering efforts were noticed.

His work caught the attention of figures like Edmund Burke Boatner, superintendent of the American School for the Deaf. Boatner, inspired by Romero’s initiative, went on to develop more refined captioning methods and co-founded the Captioned Films for the Deaf program, a US government-funded initiative that significantly advanced film accessibility.

Romero’s inventive spirit wasn’t confined to film. In 1959, he invented the Vibralarm, a vibrating alarm clock designed for the deaf and hard of hearing. This invention expanded into a product line featuring vibrating doorbells, smoke detectors, and baby alarms, showcasing his dedication to improving daily life for the deaf community through technology.

While Emerson Romero’s life is well-documented in terms of his professional achievements and contributions to the deaf community, information regarding the specific cause of Emerson Romero’s death is not readily available in the provided sources or general biographical summaries. Publicly accessible records primarily state his date of death as October 16, 1972. He passed away at the age of 72, leaving behind a legacy of innovation and advocacy.

In conclusion, while the exact details of what Emerson Romero died from might remain unknown to the general public, his impact is undeniable. Emerson Romero’s tireless efforts to bridge the gap between the hearing and deaf worlds, particularly in film and technology, cemented his place as a true pioneer. His legacy continues to inspire advancements in accessibility and serves as a powerful reminder of the importance of inclusive innovation.