Polyethylene (PE), also known as polyethene or polythene, stands as the most globally recognized and utilized plastic. This lightweight yet remarkably versatile synthetic resin belongs to the polyolefin family and is created through the polymerization of ethylene. From the everyday convenience of food wraps and shopping bags to the robust durability required for detergent bottles and even automotive fuel tanks, polyethylene’s applications are vast and varied. It can be transformed into synthetic fibers, lending itself to textiles, or modified to exhibit rubber-like elasticity.

Delving into the Chemistry and Structure of Polyethylene

Ethylene (C2H4), the foundational building block of polyethylene, is a hydrocarbon gas primarily derived from ethane cracking, a significant component of natural gas, or through petroleum distillation. At its core, an ethylene molecule comprises two methylene units (CH2) linked by a double bond (CH2=CH2). The magic of polymerization occurs when catalysts break this double bond, allowing each carbon atom to form a new single bond with a carbon atom from another ethylene molecule. This process repeats, creating long chains of repeating ethylene units – the polymer chain of polyethylene.

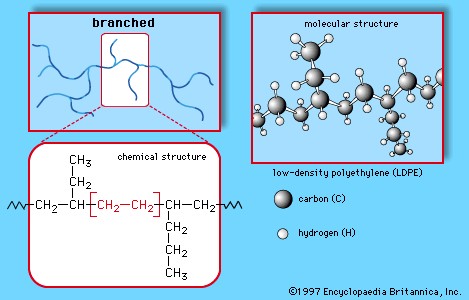

This simple, repeating structure is fundamental to polyethylene’s diverse properties. These long molecular chains, consisting of a carbon backbone with hydrogen atoms attached, can be arranged in linear or branched forms. Branched configurations result in low-density polyethylene (LDPE) and linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE), while linear arrangements lead to high-density polyethylene (HDPE) and ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE). The base polyethylene composition can be further tailored by incorporating other elements or chemical groups, leading to variants like chlorinated and chlorosulfonated polyethylene, and through copolymerization with monomers like vinyl acetate or propylene, resulting in ethylene copolymers.

A Brief History of Polyethylene Innovation

The story of polyethylene began in 1933 in England at Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). Scientists there stumbled upon low-density polyethylene (LDPE) while investigating the effects of extreme pressure on ethylene polymerization. ICI patented this groundbreaking process in 1937 and commenced commercial production in 1939. Initially, LDPE played a crucial role during World War II as insulation for radar cables.

Interestingly, an American chemist, Carl Shipp Marvel, at DuPont, had discovered a high-density polyethylene in 1930. However, its potential went unrecognized at the time. Credit for linear HDPE invention is attributed to Karl Ziegler and Erhard Holzkamp in 1953 at the Max Planck Institute for Coal Research in Germany. They achieved low-pressure catalysis using an organometallic compound. Giulio Natta further refined this process. These catalysts are now known as Ziegler-Natta catalysts, a pivotal innovation for which Ziegler received the 1963 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Since then, advancements in catalysts and polymerization techniques have enabled the creation of polyethylene with a spectrum of properties and structures, including linear low-density polyethylene (LLDPE), introduced by Phillips Petroleum Company in 1968.

Exploring the Major Types of Polyethylene

Low-Density Polyethylene (LDPE)

LDPE is produced by polymerizing gaseous ethylene under extremely high pressure (up to 50,000 psi) and high temperatures (up to 350 °C) with oxide initiators. This process results in a branched polymer structure, featuring both long and short branches. These branches prevent tight molecular packing, making LDPE a highly flexible material with a melting point around 110 °C (230 °F). LDPE is widely used in applications such as packaging films, garbage and grocery bags, agricultural film, wire and cable insulation, flexible bottles, toys, and various household items. Its plastic recycling code is #4.

Linear Low-Density Polyethylene (LLDPE)

LLDPE shares structural similarities with LDPE but is produced by copolymerizing ethylene with butene and small amounts of hexene or octene, utilizing Ziegler-Natta or metallocene catalysts. LLDPE features a linear backbone with short, uniform branches, which, like LDPE’s branches, hinder close chain packing. LLDPE exhibits properties comparable to LDPE and competes in similar markets. Its advantages lie in less energy-intensive polymerization and the ability to tailor polymer properties by adjusting chemical ingredients. LLDPE also carries the plastic recycling code #4.

High-Density Polyethylene (HDPE)

HDPE production occurs at lower temperatures and pressures using Ziegler-Natta, metallocene catalysts, or activated chromium oxide catalysts (Phillips catalysts). The linear structure of HDPE, devoid of branches, allows for tight molecular packing, resulting in a dense, highly crystalline material with significant strength and moderate stiffness. HDPE’s melting point exceeds LDPE by over 20 °C (36 °F), enabling sterilization and resistance to repeated exposure to 120 °C (250 °F). Common HDPE products include blow-molded containers for milk and cleaning fluids, grocery bags, construction and agricultural films, and injection-molded items like pails, caps, appliance housings, and toys. The plastic recycling code for HDPE is #2.

Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE)

Linear polyethylene can be manufactured in ultra-high-molecular-weight versions, boasting molecular weights from 3 to 6 million atomic units, significantly higher than HDPE’s 500,000. UHMWPE polymers can be spun into fibers and drawn or stretched to achieve a highly crystalline state, resulting in exceptional stiffness and tensile strength surpassing that of steel. These fibers are woven into high-performance materials like bulletproof vests.

Ethylene Copolymers: Expanding Polyethylene’s Functionality

Ethylene readily copolymerizes with various compounds, creating materials with enhanced properties. Ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer (EVA), produced by ethylene and vinyl acetate copolymerization under pressure with free-radical catalysts, exemplifies this. EVA copolymers, with vinyl acetate content ranging from 5 to 50%, exhibit greater gas and moisture permeability than polyethylene but are less crystalline, more transparent, and offer improved oil and grease resistance. EVA finds applications in packaging films, adhesives, toys, tubing, gaskets, wire coatings, drum liners, and carpet backing.

Ethylene-acrylic acid and ethylene-methacrylic acid copolymers, synthesized via suspension or emulsion polymerization with free-radical catalysts, incorporate acrylic acid and methacrylic acid repeating units (5-20% content).

Neutralizing the acidic carboxyl (CO2H) groups in these units with bases creates highly polar ionic groups along the polyethylene chains. These ionic groups cluster into “microdomains” due to their electric charge, enhancing stiffness and toughness without compromising moldability. These ionic polymers, known as ionomers, are transparent, semi-crystalline, and moisture-impervious. They are utilized in automotive components, packaging films, footwear, surface coatings, and carpet backing. Surlyn, a well-known ethylene-methacrylic acid copolymer, is used for durable and abrasion-resistant golf ball covers. Ethylene-propylene copolymers represent another significant category of ethylene copolymers.

In Conclusion

Polyethylene’s remarkable versatility, stemming from its simple yet adaptable chemical structure and the variety of forms it can take, has cemented its position as the world’s most indispensable plastic. From packaging to high-performance materials, polyethylene continues to play a crucial role in modern life, and ongoing innovations promise even wider applications in the future.