Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is a crucial coenzyme that powers redox reactions, making it absolutely central to energy metabolism within living organisms. Beyond this foundational role, NAD+ acts as an essential cofactor for a diverse array of non-redox NAD+-dependent enzymes. These include critical proteins like sirtuins, CD38, and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), each playing unique and vital roles in cellular function.

NAD+ exerts both direct and indirect influence over a vast spectrum of essential cellular functions. These encompass fundamental metabolic pathways that extract energy from nutrients, the intricate machinery of DNA repair that safeguards our genetic code, the dynamic process of chromatin remodeling that controls gene expression, the carefully orchestrated process of cellular senescence, and the complex functions of immune cells that defend against disease. These cellular processes and functions are not merely isolated events; they are the cornerstones of maintaining tissue and metabolic homeostasis, the delicate balance that ensures healthy aging and overall well-being.

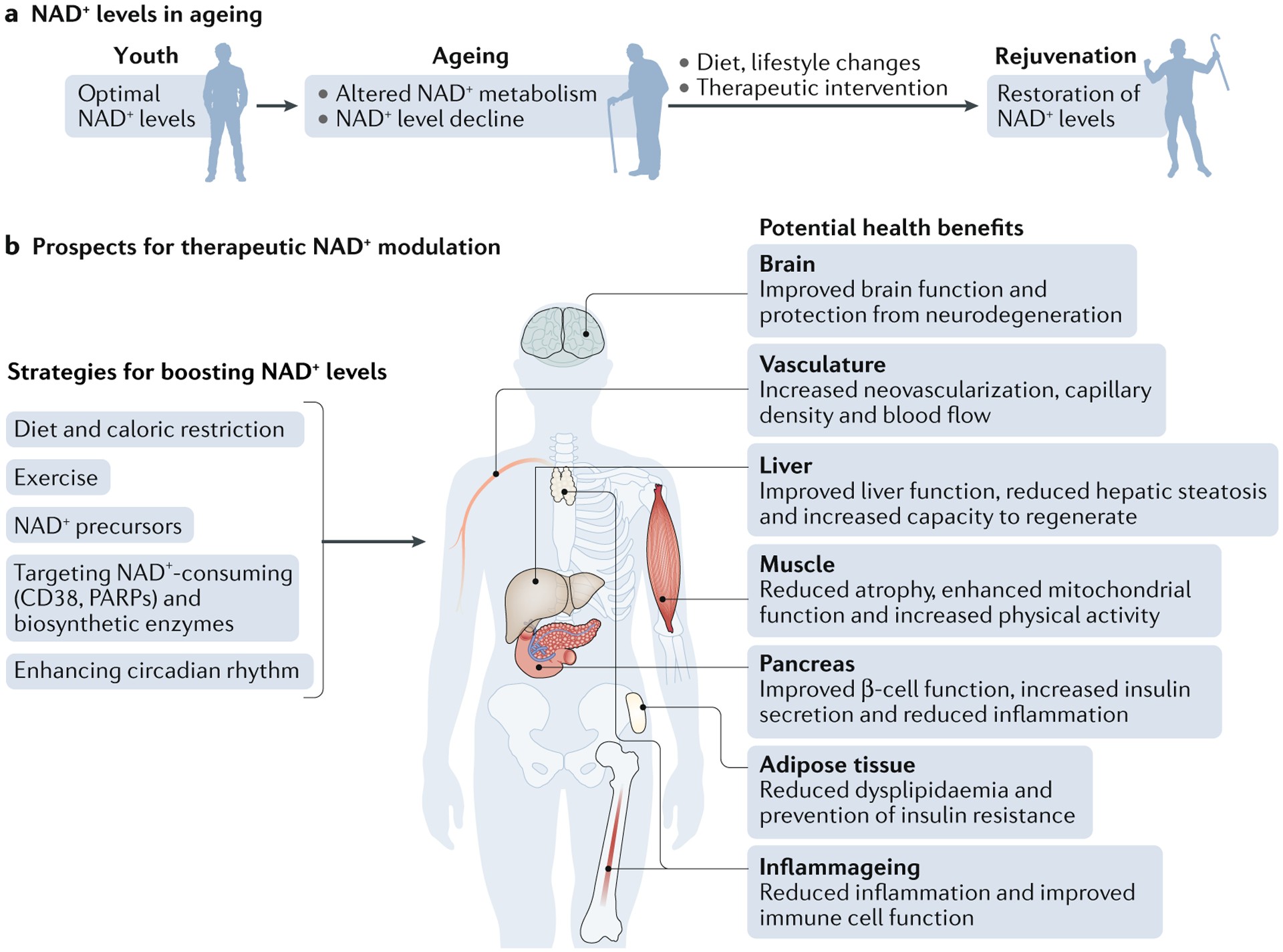

A striking feature of aging, observed across diverse model organisms from rodents to humans, is the gradual decline in tissue and cellular NAD+ levels. This reduction in NAD+ is not just a passive marker of aging; it’s causally linked to a growing list of age-associated diseases. Cognitive decline, the specter of cancer, debilitating metabolic diseases, the muscle wasting of sarcopenia, and the generalized weakness of frailty – all have been connected to dwindling NAD+ levels. Intriguingly, many of these age-related conditions can be slowed, and in some cases even reversed, by interventions that restore NAD+ levels. This remarkable potential has propelled the study of NAD+ metabolism to the forefront of therapeutic research, offering a promising avenue to combat aging-related diseases and extend not just human lifespan, but more importantly, healthspan – the years lived in good health.

However, despite the exciting progress, our understanding of NAD+’s full impact on human health and the biology of aging remains incomplete. We need to delve deeper into the molecular mechanisms that govern NAD+ levels, discover the most effective and safe strategies to restore NAD+ during aging, and rigorously assess whether NAD+ repletion truly delivers the anticipated beneficial effects in aging humans. This article aims to explore the current state of knowledge surrounding NAD+, its critical functions, its decline with age, and the therapeutic potential of targeting NAD+ metabolism to promote healthier aging.

The Central Role of NAD+ in Cellular Metabolism

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide’s (NAD+) primary claim to fame lies in its indispensable role as a coenzyme for redox reactions. This places NAD+ at the very heart of energy metabolism, the process by which cells extract and utilize energy from nutrients to fuel life’s processes. Beyond this, NAD+ is also an essential cofactor for non-redox NAD+-dependent enzymes, including sirtuins and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), expanding its influence far beyond just energy production.

NAD+ was initially recognized for its function in regulating metabolic rates within yeast extracts. Later, its role as the principal hydride acceptor in redox reactions was elucidated. This ability of NAD+ to accept a hydride ion (a proton and two electrons), transforming into its reduced form NADH, is absolutely critical for metabolic reactions across all forms of life. It is the linchpin for the activity of dehydrogenases, enzymes that drive multiple catabolic pathways, including:

- Glycolysis: The breakdown of glucose to pyruvate, a foundational step in energy extraction.

- Glutaminolysis: The breakdown of glutamine, an important energy source, particularly in rapidly dividing cells.

- Fatty acid oxidation (β-oxidation): The process of breaking down fatty acids to generate energy.

The electrons accepted by NAD+ in these catabolic reactions are not simply lost; they are strategically passed on to the electron transport chain, a molecular machine located within mitochondria (in eukaryotes). Here, through a series of carefully orchestrated steps, the energy from these electrons is harnessed to generate ATP (adenosine triphosphate), the primary energy currency of the cell.

NAD+ can also undergo phosphorylation, resulting in the formation of NADP+. Similar to NAD+, NADP+ acts as a hydride acceptor, transforming into NADPH. However, NADPH’s primary roles diverge slightly from NADH. NADPH is crucial for:

- Protection against oxidative stress: NADPH is essential for the regeneration of glutathione, a key antioxidant that neutralizes harmful reactive oxygen species (ROS).

- Anabolic pathways requiring reducing power: NADPH is vital for biosynthetic processes that require electrons for building larger molecules from smaller precursors, such as fatty acid synthesis.

In essence, NAD+ and its phosphorylated cousin NADP+ form a dynamic duo, orchestrating the flow of electrons in cellular metabolism. NAD+ fuels energy production from catabolism, while NADP+ supports biosynthesis and defense against oxidative damage.

NAD+’s Expanding Roles: Beyond Energy Metabolism

While its role in energy metabolism is paramount, NAD+’s influence extends far beyond this core function. It serves as a cofactor or substrate for hundreds of enzymes, participating in a multitude of cellular processes and functions, many of which are still under active investigation. The profound link between NAD+ levels and health was recognized nearly a century ago. In 1937, Conrad Elvehjem made a groundbreaking discovery: pellagra, a debilitating disease characterized by the “3 Ds” – dermatitis, diarrhea, and dementia – was caused by a dietary deficiency of niacin (vitamin B3). This deficiency led to critically low levels of NAD+ and NADP+ in the body, underscoring the vital importance of NAD+ for overall health.

More recently, research has solidified the connection between low NAD+ levels and a range of disease states, including metabolic and neurodegenerative disorders. Furthermore, a consistent finding across studies is that NAD+ levels decline with age in both rodents and humans. This age-related decline in NAD+ has ignited renewed interest in understanding how NAD+ metabolism impacts the origins and progression of diseases, particularly those associated with aging.

In this context, strategies aimed at restoring NAD+ levels have emerged as a promising therapeutic frontier. The use of NAD+ precursors, such as nicotinamide riboside (NR) and nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), has shown remarkable potential in preclinical studies. These precursors effectively boost NAD+ levels and have demonstrated beneficial effects in vivo, at least in rodent models, for treating age-related diseases.

This review will focus on the advancements in the NAD+ field over the past five years. We will delve into the molecular mechanisms by which NAD+ precursors, and ultimately NAD+ levels themselves, influence physiology and healthspan in the contexts of aging and disease. These mechanisms are likely intricate and multifactorial, necessitating a comprehensive exploration.

Our discussion will be structured as follows:

- NAD+ Biosynthesis and Degradation in Aging: We will examine recent discoveries regarding how the primary pathways for NAD+ production and breakdown are altered during the aging process.

- Consequences of Lower NAD+ Levels: We will discuss the potential downstream effects of reduced NAD+ levels on key molecular processes crucial to aging-related diseases. These include DNA repair, epigenetic regulation, gene expression control, cellular metabolism, and redox balance.

- NAD+-Dependent Mechanisms in Aging: We will explore the specific roles of NAD+ in various aspects of aging, including metabolic disorders, immune system dysregulation, cellular senescence, and neurodegeneration.

- Therapeutic Restoration of NAD+ Levels: We will review the wealth of recent preclinical studies investigating strategies to restore NAD+ levels as a therapeutic approach for age-related diseases. This includes studies using NAD+ precursors and small-molecule drugs that stimulate NAD+ biosynthesis.

- Prospects for NAD+-Modulating Therapies: Finally, we will discuss the various therapeutic strategies, analyze the results of recent studies, and outline the future prospects for therapies aimed at modulating NAD+ levels to promote human healthspan and lifespan.

Cellular NAD+ Metabolism: A Compartmentalized and Dynamic System

NAD+ within cells is not uniformly distributed; it exists in distinct pools within different subcellular compartments, primarily the cytoplasm, mitochondria, and nucleus. These compartments function as independent units, with NAD+ levels within each being regulated separately. Reflecting this compartmentalization, the enzymes responsible for NAD+ biosynthesis and degradation are also strategically located within these compartments.

NAD+ is a critical metabolite and coenzyme, constantly in demand for a multitude of metabolic pathways and cellular processes. Its crucial functions include:

-

Maintaining Energy Balance and Redox State: NAD+ reduction to NADH is essential for cellular respiration and maintaining the balance of reducing and oxidizing agents within the cell.

-

Substrate for NAD+-Consuming Enzymes: NAD+ is continuously turned over by three major classes of enzymes that utilize it as a substrate or cofactor:

- NAD+ glycohydrolases (NADases): This group includes CD38, CD157, and SARM1.

- Sirtuins: A family of protein deacylases involved in various cellular processes, including aging and metabolism.

- Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs): Enzymes critical for DNA repair and other cellular functions.

These NAD+-consuming enzymes generate nicotinamide (NAM) as a byproduct of their activity. This constant consumption underscores the high demand for NAD+ within the cell.

To maintain stable NAD+ levels, cells employ a critical recycling mechanism: the nicotinamide (NAM) salvage pathway. This pathway efficiently converts NAM back into NAD+, ensuring that this valuable precursor is not wasted. Furthermore, certain cells, notably in the liver, possess the capacity to synthesize NAD+ de novo, starting from dietary sources like tryptophan.

Thus, cellular NAD+ homeostasis is a dynamic equilibrium, a constant cycle of synthesis, catabolism, and recycling. This intricate system ensures that intracellular NAD+ levels remain relatively stable under normal conditions. However, this delicate balance can be disrupted during aging. NAD+ degradation can outpace the cell’s ability to synthesize NAD+ de novo or to effectively recycle NAM through the salvage pathway. Adding to this complexity, excess NAM can be diverted into alternative metabolic pathways, further reducing its availability for NAD+ regeneration and exacerbating the decline in NAD+ levels.

It’s important to note that while NAD+ glycohydrolases, sirtuins, and PARPs all consume NAD+, they have distinct roles in aging and age-related diseases. While activating sirtuins has emerged as a strategy to potentially extend lifespan and healthspan, aberrant activation of PARPs and NAD+ glycohydrolases, such as CD38, may have the opposite effect, potentially accelerating aging phenotypes.

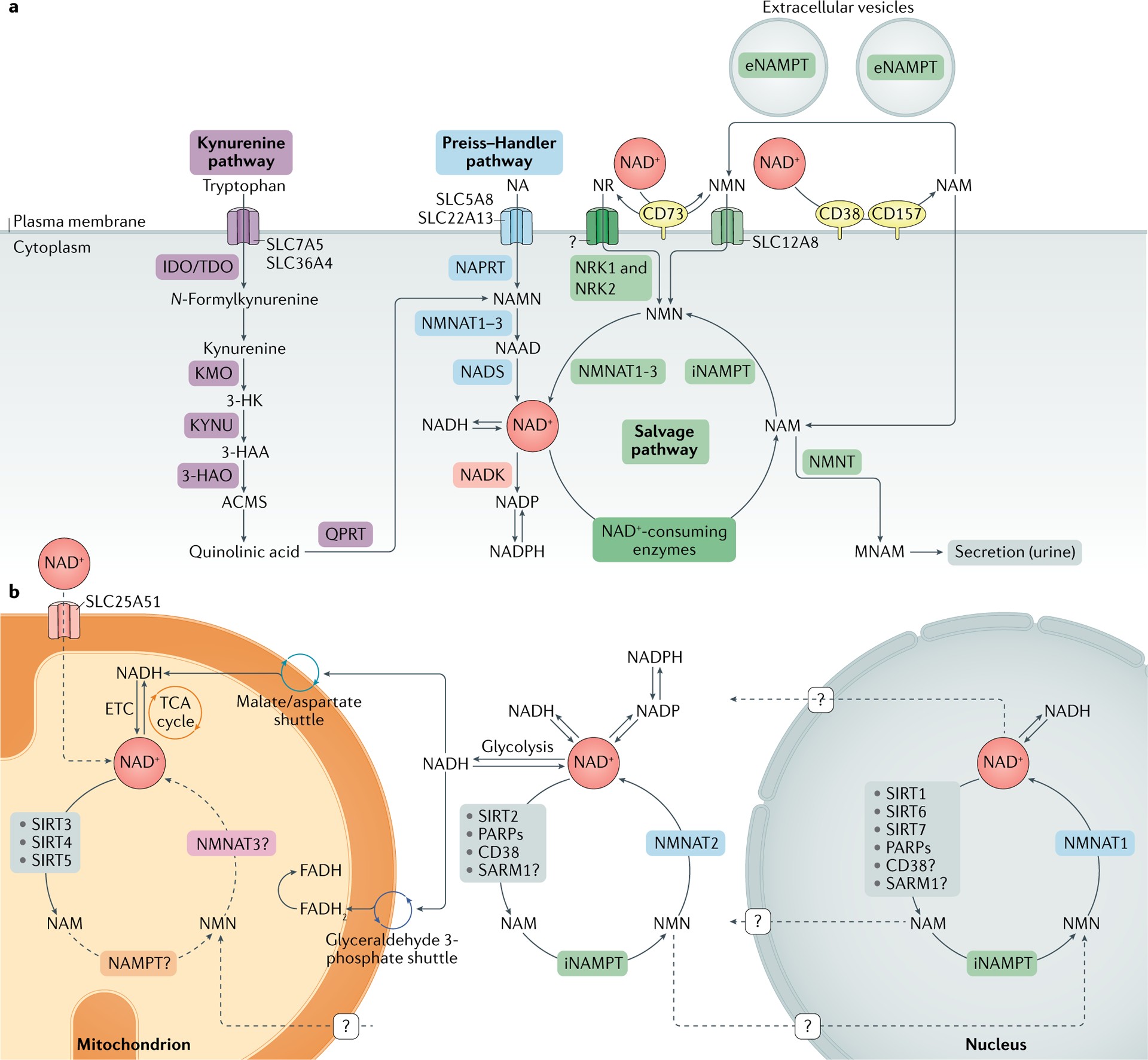

Fig. 1 |. NAD+ metabolism.

a | Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) biosynthetic pathways. NAD+ levels are maintained by three independent biosynthetic pathways. The kynurenine pathway (or de novo synthesis pathway) uses the dietary amino acid tryptophan to generate NAD+. Tryptophan enters the cell via the transporters SLC7A5 and SLC36A4. Within the cell, tryptophan is converted to N-formylkynurenine by the rate-limiting enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or the rate-limiting enzyme tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO). N-Formylkynurenine is transformed into l-kynurenine, which is further converted to 3-hydroxykynurenine (3-HK) by kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (KMO) and to 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid (3-HAA) by tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (KYNU). The next step is performed by 3-hydroxyanthranilic acid oxygenase (3HAO) to generate α-amino-β-carboxymuconate ε-semialdehyde (ACMS). This compound can spontaneously condense and rearrange into quinolinic acid, which is transformed by quinolinate phosphoribosyltransferase (QPRT) into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NAMN), at which point it converges with the Preiss–Handler pathway. The Preiss–Handler pathway uses dietary nicotinic acid (NA), which enters the cell via SLC5A8 or SLC22A13 transporters, and the enzyme nicotinic acid phosphoribosyltransferase (NAPRT) to generate NAMN, which is then transformed into nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (NAAD) by nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNAT1, NMNAT2 and NMNAT3). The process is completed by the transformation of NAAD into NAD+ by NAD+ synthetase (NADS). The NAD+ salvage pathway recycles the nicotinamide (NAM) generated as a by-product of the enzymatic activities of NAD+-consuming enzymes (sirtuins, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) and the NAD+ glycohydrolase and cyclic ADP-ribose synthases CD38, CD157 and SARM1). Initially, the intracellular nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (iNAMPT) recycles NAM into nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN), which is then converted into NAD+ via the different NMNATs. NAM can be alternatively methylated by the enzyme nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT) and secreted via the urine. In the extracellular space, NAM is generated as a by-product of the ectoenzymes CD38 and CD157 and can be converted to NMN by extracellular NAMPT (eNAMPT). NMN is then dephosphorylated by CD73 to nicotinamide riboside (NR), which is transported into the cell via an unknown nucleoside transporter (question mark). NMN can be imported into the cell via an NMN-specific transporter (SLC12A8 in the small intestine). Intracellularly, NR forms NMN via nicotinamide riboside kinases 1 and 2 (NRK1 and NRK2). NMN is then converted to NAD+ by NMNAT1, NMNAT2 and NMNAT3. b | NAD+ metabolism in different subcellular compartments. The NAD+ homeostasis is a balance of synthesis, consumption and regeneration in different subcellular compartments, which are regulated by subcellular-specific NAD+-consuming enzymes, subcellular transporters and redox reactions. NAD+ precursors enter the cell via the three biosynthetic pathways (part a). In the cytoplasm, NAM is converted to NMN by intracellular NAMPT (iNAMPT). NMN is then converted to NAD+ by NMNAT2, which is the cytosol-specific isoform of this enzyme. NAD+ is utilized during glycolysis, generating NADH, which is transferred to the mitochondrial matrix via the malate/aspartate shuttle and the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate shuttle. The mitochondrial NADH imported via the malate/aspartate shuttle is oxidized by complex I in the electron transport chain (ETC), whereas the resulting reduced flavin adenine dinucleotide (FADH2) from the glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate shuttle is oxidized by complex II. Recently the mammalian NAD+ mitochondrial transporter SLC25A51 was identified, and it has been demonstrated to be responsible for intact NAD+ uptake in the organelle. The salvage pathway for NAD+ in mitochondria has not been fully resolved, but the role of a specific NMNAT isoform (NMNAT3) has been proposed. In the mitochondria, NAD+ is consumed by NAD+-dependent mitochondrial SIRT3–SIRT5, generating NAM. It is still unknown whether NAM can be converted back to NMN or can be converted to NAD+ within the mitochondrion, or whether other precursors can be transported through the mitochondrial membrane to fuel NAD+ synthesis. The nuclear NAD+ pool probably equilibrates with the cytosolic one by diffusion through the nuclear pore; however, the full dynamics are still largely unexplored. A nuclear-specific NMNAT isoform (NMNAT1) has been described and is part of the nuclear NAM salvage NAD+ pathway. MNAM, N1-methylnicotinamide; TCA, tricarboxylic acid.

Box 1 |. Generation of NAD+ via the NAM salvage pathway

The nicotinamide (NAM) salvage pathway is a critical route for generating nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) from NAM itself, or from its upstream NAD+ vitamin precursors, nicotinamide riboside (NR) or nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN). These precursors are readily available in common foods like milk, fruits, vegetables, and meat. While NAD+ itself is not readily permeable to cell membranes, it was traditionally thought that its dietary precursors – nicotinic acid, NAM, NR, and tryptophan – could directly enter cells and be utilized for NAD+ biosynthesis, with NMN being the exception. Supporting this, extracellular NMN was believed to require conversion to NR by the enzyme 5′-nucleotidase CD73 before cellular uptake. This conversion step was considered rate-limiting, necessitating intracellular reconversion back to NMN by nicotinamide riboside kinase 1 (NRK1).

However, recent research has challenged this dogma with the discovery of a specific NMN transporter, SLC12A8. This transporter exhibits high expression in the small intestine, suggesting that NMN can indeed serve as a direct entry point into the NAD+ biosynthetic pathway. Further research is crucial to fully understand the physiological relevance of this transporter in various diseases, the precise kinetics and mechanisms of NMN uptake, and the uptake mechanisms of other NAD+ precursors. We also need to elucidate the tissue- and cell-specific expression patterns of these transporters and their differential effects across mammalian systems.

NAD+ recycling via the NAM salvage pathway is fundamental for restoring NAD+ levels after its irreversible degradation by NAD+-consuming enzymes. These enzymes, including glycohydrolases (CD38, CD157, and SARM1), protein deacylases (sirtuins), and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), all produce NAM as a byproduct of NAD+ breakdown. The NAM salvage pathway, driven by the enzyme nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), then converts this NAM back into NMN. NMN can also be generated from NR through the action of NRK1 and NRK2. In the final step of the salvage pathway, nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNAT1, NMNAT2, and NMNAT3) convert NMN into NAD+.

The three NMNAT isoforms exhibit distinct subcellular localizations: NMNAT1 in the nucleus, NMNAT2 on the cytosolic face of the Golgi apparatus, and NMNAT3 in mitochondria. These isoforms are believed to regulate NAD+ levels within their respective cellular compartments, but they also influence NAD+ stores in other intracellular locations.

NAMPT is widely expressed throughout the body and is often upregulated in processes that demand high NAD+ levels, such as immune cell activation and responses to genotoxic stress. NAMPT-mediated NAD+ biosynthesis plays a crucial role in cellular metabolism and responses to inflammatory, oxidative, and genotoxic stress by modulating the activities of sirtuins and PARPs. Furthermore, NAMPT expression is regulated by the circadian clock machinery (CLOCK–BMAL1) in a feedback loop involving SIRT1. This intricate interplay contributes to the circadian oscillation of NAD+ levels observed in vivo.

NAMPT exists in two forms in mammals: intracellular NAMPT (iNAMPT) and extracellular NAMPT (eNAMPT). To function as an NAD+ biosynthetic enzyme, NAMPT forms homodimers. Many cell types produce eNAMPT, and its secretion is actively regulated by SIRT1 or SIRT6-mediated deacetylation in adipose tissue and cancer cell lines, respectively. Intriguingly, eNAMPT is carried within extracellular vesicles in the bloodstream of both mice and humans. It enhances intracellular NAD+ biosynthesis in primary hypothalamic neurons and is believed to maintain NAD+ levels in distant cells in an autocrine fashion, and even act as an endocrine signal to influence NAD+ levels and inflammation in remote tissues.

Beyond its role in NAM salvage, eNAMPT was previously identified as a presumptive cytokine, also known as pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF). Serum levels of eNAMPT monomer are elevated in various immunological and metabolic disorders. However, it remains unclear whether NAMPT’s enzymatic activity is essential for its cytokine-like function. Distinguishing between monomeric and dimeric forms of eNAMPT may resolve the ongoing debate surrounding its enzymatic activity and broader functions. Collectively, these studies suggest that eNAMPT plays a multifaceted role, maintaining NAD+ homeostasis both locally and systemically, and acting as a signaling molecule influencing inflammation and NAD+ levels across tissues.

Box 2 |. Metabolic catabolism of NAD+ via NNMT and NADK

Nicotinamide N-methyltransferase (NNMT) is an enzyme that diverts nicotinamide (NAM) away from the NAD+ salvage pathway. It uses S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) as a methyl donor to methylate NAM, converting it into N1-methylnicotinamide (MNAM). MNAM can be further metabolized by aldehyde oxidase into N1-methyl-2-pyridone-5-carboxamide and N1-methyl-4-pyridone-3-carboxamide, which are then excreted in urine along with MNAM. This NNMT-mediated conversion of NAM to MNAM effectively prevents NAM from being recycled back into nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) via the salvage pathway, thereby impacting overall NAD+ levels. Consequently, there’s growing interest in NNMT’s role as a key regulator of NAD+ levels in disease states such as obesity, cancer, and aging.

For example, NNMT expression increases in visceral white adipose tissue and liver during obesity, often with detrimental consequences. These include depletion of the methyl donor SAM and NAD+ in white adipose tissue and liver in response to high-fat diets. Increased NNMT activity leads to reduced methylation of gene promoters involved in fibrosis and aberrant gene expression of metabolic and inflammatory genes. Thus, NNMT appears to be a critical metabolic enzyme linking NAD+ metabolism to gene expression control through its regulation of bioactive molecules like NAD+ and SAM and the production of MNAM.

NNMT’s role in regulating NAD+ suggests its potential involvement in aging. Supporting this, the Caenorhabditis elegans homolog of NNMT, ANMT-1, regulates MNAM production. In worms, MNAM serves as a substrate for aldehyde oxidase GAD-3, which produces hydrogen peroxide. Hydrogen peroxide, in turn, acts as a hormesis signal, promoting longevity. Worms lacking anmt-1 lose the lifespan extension benefit associated with sir-2.1 activity. These findings suggest that NAD+ consumption via NNMT might be beneficial for lifespan extension, at least in C. elegans.

However, NNMT’s role in mammalian aging is less clear. While NNMT expression and activity seem to increase with age in rodents, early evidence suggests that NNMT may promote aging-related diseases in mammals, contrasting with its potential beneficial role in C. elegans. For instance, studies have shown increased NNMT gene expression in hepatocytes of aging mice and older mice fed high-protein diets. Furthermore, inhibiting NNMT in old mice activated senescent muscle stem cells and promoted muscle regeneration during aging. This suggests that targeting NNMT could be a therapeutic approach for aging-related diseases in mammals.

Another metabolic fate of NAD+ is direct phosphorylation by NAD+ kinase (NADK) to produce NADP(H). NADP(H) is crucial as a major source of reducing power, regulating intracellular redox balance and anabolic processes like lipogenesis. Isotopic tracing studies indicate that NADK accounts for approximately 10% of NAD+ consumption. However, the total NADP+ pool is significantly smaller than the NAD+ pool (about 20 times less). Moreover, NADP+ levels tend to decline in parallel with NAD+ levels in conditions of NAD+ depletion, such as aging. This suggests that NADP+ levels are directly linked to NAD+ levels and that NADK is unlikely to be a major NAD+ sink in most scenarios.

However, recent research has shown that NADK is a direct target of AKT kinase. AKT phosphorylation of NADK at residues Ser44, Ser46, and Ser48 enhances NADK activation. Given that AKT signaling is often abnormally increased during aging, aberrant activation of NADK might contribute to the age-related decline in NAD+ levels. Further studies are needed to fully elucidate the role of NADK in regulating NAD+ and NADP+ pools during aging and in aging-related diseases.

NAD+ Biosynthetic Pathways: De Novo Synthesis and Salvage

NAD+ can be synthesized through two primary routes:

- De novo synthesis (Kynurenine pathway): This pathway starts from the amino acid l-tryptophan.

- Preiss–Handler pathway: This pathway utilizes vitamin precursors, such as nicotinic acid (NA).

FIG. 1a illustrates these pathways in detail. In addition to NAD+, the kynurenine pathway also produces other bioactive molecules from l-tryptophan, including kynurenic acid, serotonin, and picolinic acid. However, the relative contribution of de novo synthesis to overall NAD+ levels is still not fully understood.

Outside the liver, most cells lack the complete set of enzymes needed to convert tryptophan to NAD+ via the kynurenine pathway. Instead, the liver plays a central role in de novo NAD+ synthesis. Most tryptophan is metabolized to NAM in the liver, which is then released into the bloodstream. Peripheral cells can then take up this NAM and convert it to NAD+ through the NAM salvage pathway. In certain circumstances, immune cells, such as macrophages, can also synthesize NAD+ from tryptophan.

Therefore, while the de novo biosynthetic pathway exists in most cells, it appears to be a more indirect contributor to system-wide NAD+ levels. The majority of NAD+ is thought to originate from the NAM salvage pathway, highlighting its critical importance in maintaining cellular NAD+ homeostasis. BOX 1 provides further details on the NAM salvage pathway.

NAD+ Consumption Routes: Sirtuins, PARPs, CD38, and SARM1

NAD+ levels are not simply determined by synthesis; they are also significantly influenced by consumption. Several enzyme families utilize NAD+ as a substrate, leading to its breakdown. Understanding these consumption routes is crucial for comprehending NAD+ dynamics and developing strategies to modulate its levels. The major NAD+-consuming enzyme families include:

Consumption by Sirtuins

Sirtuins have garnered significant attention since their discovery due to their roles in regulating key metabolic processes, stress responses, and aging biology. The mammalian sirtuin family comprises seven proteins (SIRT1–SIRT7), each with distinct subcellular localizations, enzymatic activities, and downstream targets.

- Nuclear sirtuins: SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7 (SIRT1 also found in the cytosol).

- Nucleolar sirtuin: SIRT7.

- Mitochondrial sirtuins: SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5.

- Cytosolic sirtuins: SIRT1, SIRT2, and SIRT5.

FIG. 1b illustrates the subcellular distribution of sirtuins. This compartmentalization underscores how localized fluctuations in intracellular NAD+ pools can selectively impact organelle-specific sirtuin functions and cellular metabolism.

Sirtuins are constitutively active in cells. SIRT1 and SIRT2 are estimated to account for about one-third of total NAD+ consumption under basal conditions. Furthermore, NAD+ levels are strongly correlated with sirtuin activation during fasting and caloric restriction. Sirtuin activity is also linked to the circadian clock. SIRT1 and SIRT6 regulate the activity of core clock transcription factors and downstream circadian gene expression. Moreover, SIRT1 and NAMPT, a key enzyme in the NAD+ salvage pathway, are central to the circadian regulation of NAD+ levels. NAMPT itself is regulated by the circadian clock, creating a feedback loop that results in circadian oscillations of NAD+ levels.

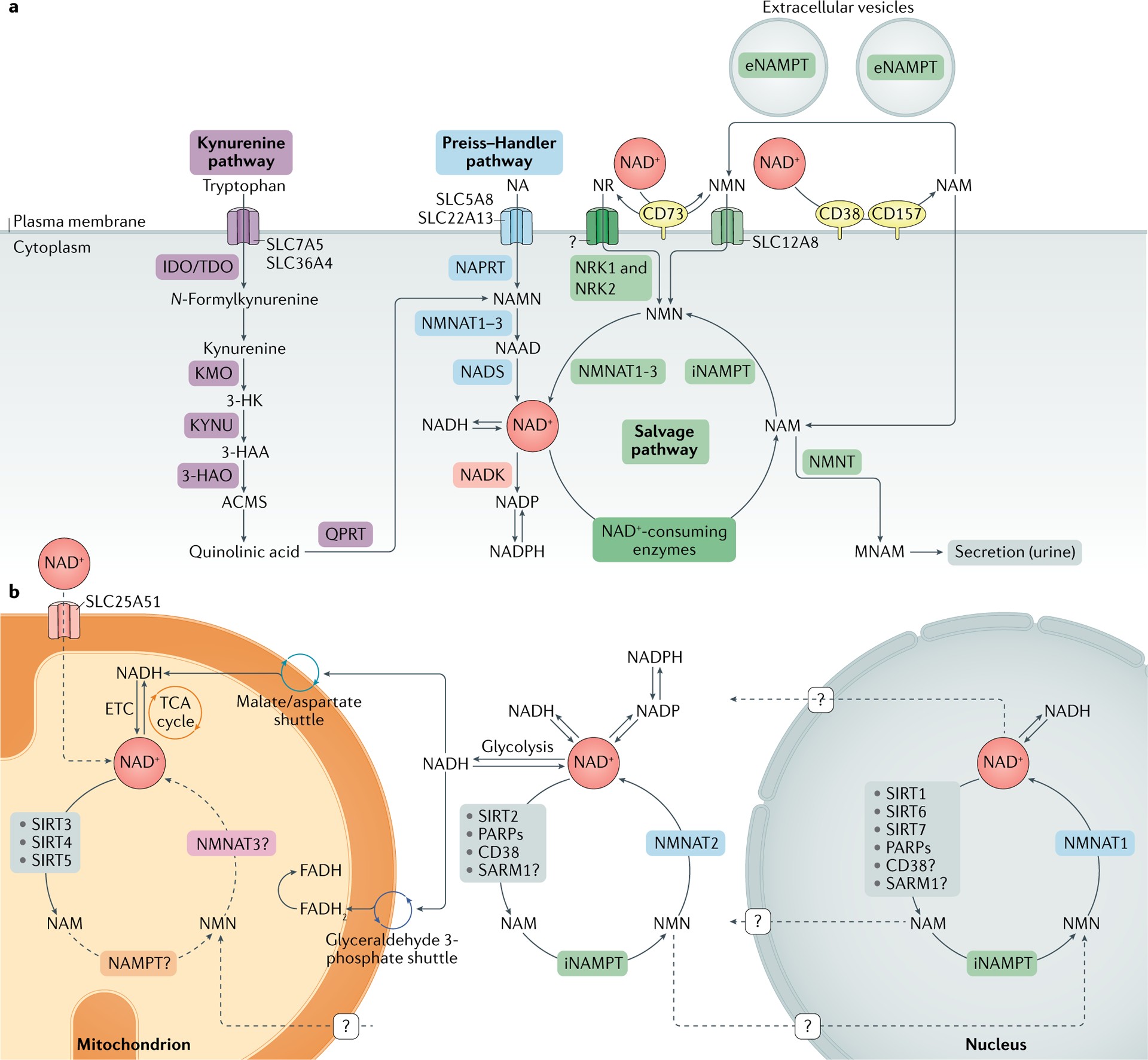

Early research in yeast revealed sirtuins’ roles in gene silencing, which was later attributed to their NAD+-dependent deacetylase activity. Sirtuins primarily remove acetyl groups from lysine residues on target proteins. This deacetylation reaction involves a two-step process:

- NAD+ is cleaved to NAM and ADP-ribose.

- The acetyl group from the target protein is transferred to ADP-ribose, forming a peptidyl-ADP-ribose intermediate. Acetyl-ADP-ribose is subsequently released. FIG. 2a illustrates this mechanism.

In addition to deacetylase activity, some sirtuins mediate non-acetyl lysine deacylations, such as the removal of succinyl, malonyl, and fatty acyl groups. The cellular functions of these non-deacetylase activities are still being investigated. SIRT4 and SIRT6 also function as ADP-ribosyltransferases, suggesting that sirtuins contribute to cell regulation through mechanisms beyond protein deacetylation. These alternative functions require further exploration.

Recent technological advancements have provided insights into the distinct cellular roles of sirtuins. Nuclear sirtuins (SIRT1, SIRT6, and SIRT7) are critical regulators of DNA repair and genome stability. Mitochondrial sirtuins (SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5) and nuclear SIRT1 regulate mitochondrial homeostasis and metabolism. SIRT1 has been implicated in both mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy (the removal of damaged mitochondria), suggesting its central role in maintaining mitochondrial quality.

Overall, sirtuins have emerged as key players in understanding how NAD+ levels influence cellular homeostasis across a wide range of processes impacting aging. Boosting sirtuin activity is a major focus of therapies aimed at counteracting aging.

Consumption by PARPs

The human PARP protein family consists of 17 members, characterized by poly(ADP-ribosyl) polymerase or mono(ADP-ribosyl) polymerase activity. PARPs cleave NAD+ to produce NAM and ADP-ribose. ADP-ribose is then added as single units or covalently linked polymers to PARP itself and other acceptor proteins, a process called poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation (PARylation). FIG. 2b depicts PARP activity.

Among PARPs, only PARP1, PARP2, and PARP3 localize to the nucleus FIG. 1b and play a key role in DNA damage repair. PARP1 is the most well-characterized PARP, responsible for approximately 90% of total PARP activity, particularly in response to DNA damage. Upon activation by DNA damage, PARP1 PARylates itself, histones, and other proteins, creating a scaffold to recruit and activate other DNA repair enzymes. High PARP1 activity associated with DNA damage leads to substantial NAD+ consumption.

PARP1, as an NAD+-responsive signaling molecule, is strongly linked to the aging process. It is a major NAD+ consumer not only during acute DNA damage but also under normal and pathophysiological conditions, highlighting its role in NAD+ homeostasis. For example, mice on a high-fat diet treated with PARP inhibitors or lacking PARP1 and PARP2 exhibit increased NAD+ levels, enhanced SIRT1 activity, improved mitochondrial function, and protection from insulin resistance.

The correlation between PARP1 activation, NAD+ decline, and SIRT1 inhibition is observed in patients with xeroderma pigmentosum group A, progeroid diseases, ataxia telangiectasia, and Cockayne syndrome. Treating mice with Cockayne syndrome with PARP1 inhibitors or NAD+ supplements extended lifespan and ameliorated disease phenotypes, suggesting that the negative consequences of PARP1 hyperactivation are mediated by NAD+ dysregulation in response to extensive DNA damage and genotoxic stress.

PARP1 and SIRT1 likely compete for the same nuclear NAD+ pool. PARP1’s higher affinity for NAD+ (lower Km) and faster reaction rate (Vmax) likely allow it to outcompete SIRT1 for NAD+, especially when PARP1 is highly activated.

PARP2 is structurally similar to PARP1 and shares a catalytic domain. It accounts for about 10% of PARP activity and also influences NAD+ bioavailability. Similar to Parp1-knockout mice, Parp2-knockout mice show enhanced SIRT1 activity, improved metabolic function, and protection against high-fat diet-induced obesity. PARP3 also plays a role in DNA repair, suggesting overlap and redundancy among PARP1, PARP2, and PARP3. The functions of other PARPs (PARP4–PARP17) in NAD+ homeostasis and metabolism are less well-defined, but they are thought to have a smaller impact on intracellular NAD+ levels.

Targeting PARPs, particularly PARP1, is a promising therapeutic strategy in the aging field. However, further research is needed to fully understand the contribution of PARPs to the age-related decline in NAD+ levels.

Consumption by CD38 and CD157

CD38 and CD157 are multifunctional ectoenzymes with both glycohydrolase and ADP-ribosyl cyclase activities. Their primary catalytic activity is NAD+ glycohydrolysis, cleaving NAD+ into NAM and ADP-ribose. They also exhibit ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity, generating cyclic ADP-ribose from NAD+. CD38 can also perform a base-exchange reaction under acidic conditions, swapping NAM for nicotinic acid (NA) in NAD(P)+, producing nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (NAAD(P)). FIG. 2c illustrates these reactions.

Cyclic ADP-ribose, NAAD(P), and ADP-ribose are all key Ca2+-mobilizing second messengers. This highlights CD38’s pivotal role in Ca2+ signaling and modulating essential cell processes like immune cell activation, survival, and metabolism. Beyond NAD+ and NADP+, CD38 can also use NMN as a substrate, while CD157 can utilize NR. Thus, inhibiting CD38 and CD157 could enhance the efficiency of NAD+ precursor metabolites in restoring NAD+ levels, particularly in aging individuals. The enzymatic functions of CD157 in cellular biology and aging are less well-understood than those of CD38, but recent evidence suggests that CD157, like CD38, is upregulated in aging tissues and may contribute to age-related diseases like rheumatoid arthritis and cancer.

While CD38 and CD157 are homologous and belong to the same enzyme family, they differ in structure, localization, and disease roles. CD38 is a transmembrane protein expressed ubiquitously, especially during inflammation. CD157 is a glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored protein, initially identified in myeloid cells but also expressed by other cell types.

In addition to their enzymatic functions, CD38 and CD157 act as cell receptors. For example, CD38 interacts with CD31 as an adhesion receptor, mediating immune cell trafficking and extravasation through the endothelium. The CD38–CD31 axis may promote proliferation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia lymphocytes, suggesting a detrimental role of CD38 in blood cancers. However, the functional consequences of CD38–CD31 interaction are still largely unknown. CD38 also appears to mediate immunity through antimicrobial functions, as Cd38-knockout mice exhibit impaired immune responses to bacteria. It is plausible that CD38’s role in antimicrobial resistance involves sequestering NAD+ or NAD+-related metabolites from bacteria that require NAD+ for survival.

CD157’s receptor functions are less explored. Evidence suggests that CD157 activation by monoclonal antibodies promotes neutrophil and monocyte trafficking. CD157 also interacts with integrins, forming a receptor for scrapie-responsive gene 1 protein (SCRG1), promoting self-renewal, migration, and osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. However, the relevance of these receptor functions to NAD+ metabolism remains unclear.

Consumption by SARM1

SARM1 was recently classified into the NAD+ glycohydrolase and cyclase family alongside CD38 and CD157. SARM1’s enzymatic activity relies on its Toll/interleukin receptor (TIR) domain, previously not known to have catalytic activity and primarily associated with protein-protein interactions. The extent to which SARM1 regulates NAD+ under physiological conditions is still being investigated. However, SARM1-mediated NAD+ degradation plays a key role in axonal degeneration following axonal injury.

SARM1 is primarily expressed in neurons and promotes neuronal morphogenesis and inflammation. It is also expressed by immune cells like macrophages and T lymphocytes, regulating their functions. SARM1 was initially identified as a negative regulator of innate immunity by interacting with TRIF, downstream of Toll-like receptor signaling. However, its immunoregulatory role is still largely uncharacterized and somewhat controversial. Despite initial reports, recent evidence suggests SARM1 is not significantly expressed in macrophages, and earlier chemokine phenotype observations in Sarm1-knockout mice may have been due to background effects.

Despite its debated role in immune cells, SARM1’s key role in axonal degeneration is undisputed, making it a therapeutic target for neurodegenerative diseases and traumatic brain injuries, as discussed further in the Neurodegeneration section.

Fig. 2 |. Three main classes of NAD+-consuming enzymes.

a | Sirtuins remove acyl groups from lysine residues on target proteins using nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) as a co-substrate. NAD+ is cleaved, generating nicotinamide (NAM) and ADP-ribose, where ADP-ribose serves as an acyl group acceptor, generating acetyl-ADP-ribose (acetyl-ADPR). b | Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARP1–PARP3) use NAD+ as a co-substrate to mono(ADP-ribosyl)ate or poly(ADP-ribosyl)ate target proteins, generating NAM as a by-product. c | Reactions of NAD+ glycohydrolases and cyclic ADP-ribose (cADPR) synthases (CD38, CD157 and SARM1). The main catalytic activity of this group of proteins is the hydrolysis of NAD+ to NAM and ADP-ribose. To a lesser extent, CD38, CD157 and SARM1 have ADP-ribosyl cyclase activity, generating NAM and cADPR from NAD+. In acidic conditions, CD38 can also perform a base-exchange reaction, swapping the NAM of NAD(P)+ for nicotinic acid (NA), generating nicotinic acid adenine dinucleotide (phosphate) (NAAD(P)). CD38 and CD157 are reported to be able to use alternative substrates in their catalytic reactions. CD38 can degrade NMN to NAM and ribose monophosphate (RMP), while CD157 can degrade NR, generating NAM and ribose (R). NR, nicotinamide riboside.

Cellular Roles of NAD+: Beyond the Major Consumers

Beyond the primary NAD+-consuming enzyme families discussed, NAD+ serves as a cofactor or substrate for over 300 enzymes, highlighting its widespread involvement in cellular biochemistry. It mediates crucial cellular functions and adaptations to metabolic demands. These critical processes include:

- Metabolic pathways: NAD+ is fundamental for glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, fatty acid oxidation, and other core metabolic processes.

- Redox homeostasis: NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH ratios play vital roles in maintaining cellular redox balance.

- DNA maintenance and repair: NAD+-dependent enzymes like sirtuins and PARPs are crucial for genome stability.

- Epigenetic regulation and chromatin remodeling: Sirtuins, as deacetylases, influence chromatin structure and gene expression.

- Autophagy: NAD+ and sirtuins regulate autophagy, the cellular self-cleaning process.

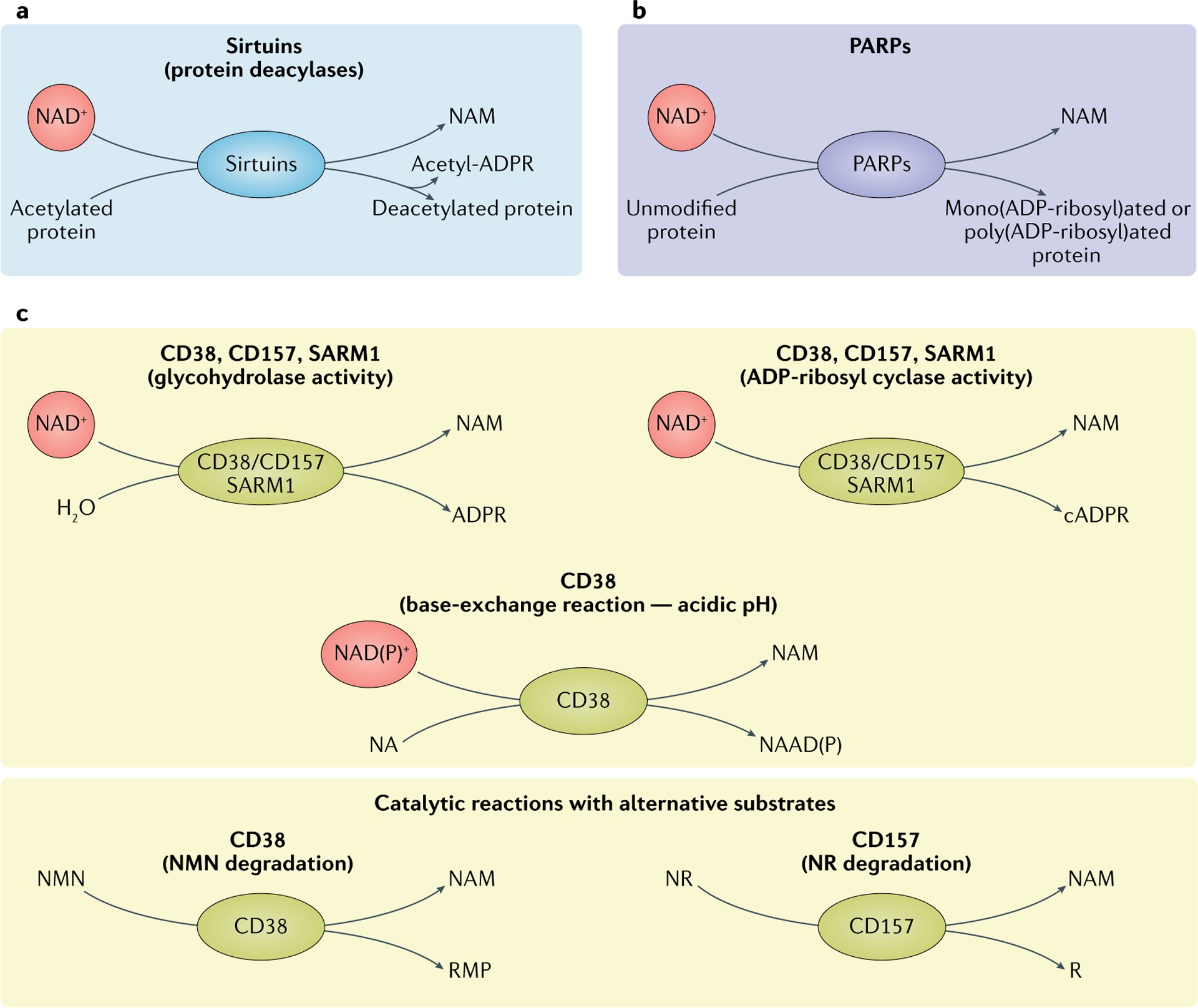

Collectively, these functions are essential for maintaining systemic health and homeostasis. However, during aging, declining NAD+ levels can compromise these processes, exacerbating age-related diseases. FIG. 3 and Supplementary Box 2 further detail the impact of NAD+ decline on aging.

NAD+-Dependent Mechanisms in Aging: Metabolic Dysfunction, Immune Deregulation, Senescence, and Neurodegeneration

As we age, NAD+ levels consistently decline, and alterations occur in the enzymes involved in NAD+ degradation and biosynthesis. The relationship between NAD+ and the ten hallmarks of aging has been extensively reviewed. This age-related NAD+ decline is linked to the development and progression of various age-related diseases, including atherosclerosis, arthritis, hypertension, cognitive decline, diabetes, and cancer.

This section focuses on key cellular processes influenced by or influencing aging, such as metabolic dysfunction, DNA repair failure, genomic instability, inflammaging, cellular senescence, and neurodegeneration, and their regulation by NAD+ levels. These processes and associated age-related disorders are potential targets for NAD+ repletion therapies. Restoring NAD+ levels through dietary precursors or inhibiting NAD+ degradation enzymes offers a promising therapeutic strategy to mitigate age-related decline and diseases. FIG. 4 illustrates these therapeutic approaches.

Metabolic Dysfunction and NAD+

Obesity is a global health crisis, increasing the risk of metabolic diseases characterized by increased adiposity, insulin resistance, high blood glucose, hypertension, and dyslipidemia. These conditions elevate the risk of type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, atherosclerosis, stroke, and cancer. Obesity accelerates aging and is associated with reduced lifespan. Targeting NAD+ metabolism has emerged as a promising therapeutic avenue for metabolic disease and aging.

NAD+’s role in regulating metabolic rates has been known for nearly a century. It is central to metabolic flux in multiple pathways. NAD+ homeostasis is essential for proper function of metabolic tissues like fat, muscle, intestines, kidneys, and liver. The discovery that Sir2 (yeast sirtuin) promotes longevity in an NAD+-dependent manner highlighted the link between NAD+ and lifespan.

Lifespan-extending interventions like exercise, caloric restriction, time-restricted feeding, ketogenic diets, and healthy circadian rhythms partially work by increasing NAD+ levels and activating sirtuins. Conversely, metabolic disruptions like high-fat diets, postpartum weight loss, and circadian rhythm disruption can lower NAD+ levels, reducing sirtuin activity and other NAD+-dependent processes. Increasing NAD+ levels can reduce reductive stress and enhance the activity of SIRT1 and SIRT3, which regulate mitochondrial function and protect against high-fat diet-induced metabolic disease.

Studies in Parp1-knockout, Cd38-knockout mice, and mice treated with PARP or CD38 inhibitors, which have elevated NAD+ levels, show protection from obesity, increased metabolic rates, and improved glucose metabolism during high-fat diets and aging. High-fat diets induce inflammation, reducing NAMPT expression and NAD+ salvage pathway activity, potentially explaining NAD+ decline in obesity. Adipocyte-specific NAMPT deletion in mice leads to lower fat tissue NAD+, insulin resistance, and metabolic dysfunction, rescued by NMN supplementation. NAD+ supplements (NR and NMN) also protect against obesity in rodent models.

Clinical trials are investigating NAD+ precursors in humans with obesity to improve metabolic health. While early trials in healthy individuals have established safe doses for boosting NAD+ levels, recent randomized, double-blind studies in overweight and obese patients using NR for 6 and 12 weeks showed effective NAD+ level increases but no significant improvements in weight loss, insulin sensitivity, mitochondrial function, or other metabolic parameters. Therefore, the efficacy of targeting NAD+ metabolism for metabolic disease in obese or aging humans remains unclear.

Table 1 |.

Preclinical studies in mouse models of human diseases using NAD+-boosting strategies

| Mechanism of action | Compound | Model | Outcome | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NAD+ precursors | Nicotinamide | High-fat diet-fed and standard diet-fed male C57BL/6J wild-type mice | Prevents diet-induced hepatosteatosis and improves glucose metabolism and redox status in liver. Increases pentose phosphate pathway and reduces protein carbonylation. No change in lifespan | 200 |

| Alzheimer disease-relevant 3xTgAD mice | Increases of antioxidant levels, autophagy-lysosome clearance and oxidative stress resistance/mitochondrial function/integrity. Decreases of Aβ peptide and phosphorylated tau levels. Improvements in neuronal plasticity/cognitive function | 233 | ||

| NMN | Male C57BL/6N wild-type mice | Inhibits age-induced weight gain, increases insulin sensitivity, plasma lipid levels, physical activity and energy expenditure and improves muscle mitochondrial function | 199 | |

| C57BL/6J wild-type mice | Enhances skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative metabolism in aged mice | 201 | ||

| Male Long-Evans ratsIschaemia-reperfusion or cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury in *Sirt1*+/− mice, C57BL/6 mice and 129S2/Sv mice | Improves mitochondrial function, decreases inflammation, improves physiologic reserve and decreases mortality, despite having no major effect on blood pressure or oxidative damageProtects renal function from cisplatin-induced injury in wild-type mice but not in *Sirt1*+/− mice | 202,204 | ||

| High-fat diet-induced obese female mice | Improves glucose tolerance and increases liver citrate synthase activity and triglyceride accumulation | 203 | ||

| Transverse aortic constriction-stressed mice, male conditional knockout miceMale cardiac-specific Fxn-knockout mice (Friedreich ataxia cardiomyopathy model) and male Sirt3-knockout/Fkn-knockout mice | Improves mitochondrial function and protects mice from heart failureImproves cardiac functions and reduces energy waste and improve energy utilization in Fxn-knockout mice but not in Sirt3-knockout/Fkn-knockout mice | 205,207 | ||

| Rod-specific Namp-knockout mice, light-induced retinal dysfunction (129S1/SvlmJ) | Rescues retinal degeneration and protects the retina from light-induced injury | 206 | ||

| Alzheimer disease-relevant (AD-Tg) male and female mice | Decreases APP levels and increases mitochondrial function | 161 | ||

| Male C57BL/6 miceMale C57BL/6 male | Improves carotid artery endothelium-dependent dilationRescues neurovascular coupling responses by increasing endothelial NO-mediated vasodilation and improves spatial working memory and gait coordination | 208,209 | ||

| Intracerebroventricular infusion of Aβ1–42 oligomer in male Wister ratsAPPswe/PS1dE9 transgenic mice (Alzheimer disease model) and wild-type mice | Improves learning and memory Improves cognitive function | 176,177 | ||

| Cerebral ischaemia in male C57BL/6 miceCollagen-induced intracerebral haemorrhage in male CD1 miceMale tissue plasminogen activator-treated cerebral ischaemia CD1 mice | Reduces cell death of neurons and improves neurologica outcomeReduces brain oedema and cell death and promotes the recovery of body weight and neurological functionDecreases mortality, brain infarction, oedema, apoptosis and haemorrhage and protects blood-brain-barrier integrity | 234–236 | ||

| Male and female *Tg(SIRT2);Bubr1*H/+ mice | Increases NAD+ levels and restores BubR1 levels | 237 | ||

| Nicotinamide riboside | C57BL/6 wild-type or muscle-specific Nampt-knockout (male or female) miceWild-type or mdx mice, and Mdx/Utrn-knockout miceMale C57BL/6 muscle stem cell-specific Sirt1– knockout mice and mdx mice70–80-year-old men | Restores muscle mass, force generation, endurance and mitochondrial respiratory capacity in Nampt-knockout miceImproves muscle function and reduces heart diseaseImproves endurance, grip strength and recovery from cardiotoxin-induced muscle injury in aged mice, induces the mitochondria unfolded protein response and delayed senescence in stem cells, and increases lifespanSuppresses specific circulating inflammatory cytokine levels; no change in mitochondrial biogenesis and metabolism | 188,197,198,238 | |

| Male high- fat diet- fed C57BL/6 wild- type, high- fat diet- fed liver- specific Sirt1– knockout and high- fat diet- fed Apoe– knockout KK/HIJ miceMale C57BL/6 wild- type or liver- specific Nampt– knockout mice | Prevents fatty liver and induces the mitochondrial unfolded protein response with diminished effects in Sirt1– knockout miceImproves glucose homeostasis, increases adiponectin level, and lowers hepatic cholesterol level. Improves liver regeneration, reduces hepatic steatosis and reverses the poor regeneration phenotype in liver- specific Nampt– knockout mice | 239–241 | ||

| Female Sprague Dawley ratsMale high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6 wild-type mice | Prevents or reverses paclitaxel-induced hypersensitivity to pain, no change in locomotor activityImproves glucose tolerance, reduces weight gain and hepatic, steatosis and protects against diabetic neuropathy | 242,243 | ||

| C57BL/6 wild- type or Xpa−/−/Csa−/− miceMale C57BL/6 wild- type and Atm−/− miceMale C57BL/6 wild- type and Csbm/m mice | Lowers mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species productionImproves motor coordination and behaviour and increases the number of Purkinje cells and Atm−/− mouse LifespanImproves the function of mitochondria isolated from cerebellum | 33,135,244 | ||

| 3xTgAD and 3xTgAD/Polb+/− miceiPS cell- derived dopaminergic neurons from patients with GBA- related PD | Decreases phosphorylated tau levels, no effect on Aβ levels, increases neurogenesis, LTP and cognitive function, and reduces neuroinflammation (NLRP3, caspase 3)Ameliorates mitochondrial function by increasing the mitochondrial unfolded protein response (HSP60) and increases autophagy and lysosomal function | 137,175 | ||

| Cisplatin- induced acute kidney failure in C57Bl/6NTac mice | Decreases blood urea nitrogen levels and levels of markers od glomerular dysfunction | 211 | ||

| NAD+ biosynthesis modulators | P7C3 | Osteosarcoma cell line U2OS and lung cancer cell line H2122 cells | Protects cultured cells from doxorubicin-mediated toxicity by enhancing NAMPT activity | 214 |

| SBI-797812 | Lung carcinoma A549 cells and male C57BL/6J mice | Increases NMN and NAD+ levels by increasing NAMPT activity and modest increase of hepatic NAD+ levels in mice | 214,215 | |

| TES-991 and TES-102524 | MCD diet- induced non- alcoholic fatty liver disease and ischaemia–reperfusion- induced acute kidney injury in male C57BL/6J wild- type mice | Boosts de novo NAD+ synthesis by inhibiting ACMSD and increases mitochondrial functions in liver, kidney and brain | 216 | |

| CD38 inhibitors | Apigenin | High-fat diet-fed C57BL/6 wild-type mice | Decreases global protein acetylation and improves glucose and lipid homeostasis | 226 |

| Luteolinidin | Heart ischaemia-reperfusion model in male Sprague Dawley rats | Improves vascular and cardiac contractile function by restoring NADP(H) and NAD(H) pools | 228 | |

| 78c | Diet- induced obese C57Bl6 wild- type miceC57BL/6 wild-type miceHeart ischaemia–reperfusion model in male C57Bl/6J wild- type mice | Elevates NAD+ levels in liver and muscleImproves glucose tolerance, muscle function, exercise capacity and cardiac function by mitigating mTOR– p70S6K/ERK and telomere- associated DNA damage PathwaysProtects against both postischaemic endothelial and cardiac myocyte injury. Enhances preservation of contractile function and coronary flow, and decreases infarction | 91,230,231 |

Aβ, amyloid-β ; ACMSD, α-amino-β-carboxymuconate ε-semialdehyde decarboxylase; APP, amyloid precursor protein; GBA, β-glucocerebrosidase; iPS cell; induced pluripotent stem cell; LTP, long-term potentiation; MCD diet, methionine–choline-deficient diet; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NAMPT, nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase; PD, Parkinson disease.

Immune Cell Dysfunction and Inflammaging

Inflammaging, chronic low-grade inflammation associated with aging, is recognized as a key driver of age-related diseases and a significant risk factor for morbidity and mortality. Chronic inflammation profoundly affects systemic metabolism through complex interactions between immune and metabolic cells, impacting glucose and lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity. However, the role of NAD+ in chronic inflammation and immune cell function is still emerging.

Innate Immunity and NAD+

Chronic low-grade inflammation, driven by aberrant innate immune system activation, increased proinflammatory cytokines (TNF, IL-6, IL-1β), and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, is a hallmark of aging and metabolic diseases. Altered macrophage activation and polarization are key sources of this inflammation. In obese tissues, proinflammatory M1-like macrophages infiltrate, displacing anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages, leading to increased proinflammatory cytokines, insulin resistance, and reduced lipolysis. Aging is associated with increased macrophage abundance and altered polarization and function, contributing to inflammaging.

Early studies showed that inhibiting NAMPT and depleting NAD+ in macrophages reduced proinflammatory cytokine secretion and altered cell morphology. Recent studies confirm that NAD+ regulates macrophage function, with macrophage activation linked to upregulation of NAD+ biosynthetic or degradative pathways, depending on the acquired phenotype. Proinflammatory (M1) macrophage polarization is associated with increased CD38 expression and NAD+ consumption. Anti-inflammatory (M2) polarization is linked to increased NAD+ levels dependent on NAMPT. Blocking the NAM salvage pathway reduced gene expression associated with both M1 and M2 phenotypes, rescued by NMN and NR supplementation. M2 macrophages required more NR/NMN for rescue, suggesting NAD+ is crucial for general macrophage activation, with differentially regulated metabolism controlling distinct functions in M1 and M2 macrophages.

Consistent with these findings, M1 polarization is associated with enhanced NAD+ degradation, and NAMPT inhibition blocks glycolytic shifts in M1 macrophages, limiting proinflammatory responses in vitro and reducing systemic inflammation in sepsis. This NAD+ turnover in early M1 polarization has been attributed to reactive oxygen species-induced DNA damage and PARP1 activation in some studies. However, other research suggests CD38 is the primary NAD+-consuming enzyme in M1 macrophages, with no evidence of DNA damage or PARP1 activation during M1 polarization. These conflicting observations highlight the need to further investigate the major NAD+ consumers during macrophage polarization and the molecular mechanisms by which NAD+ levels influence macrophage function and gene expression.

In aging, declining NAD+ levels are associated with increased accumulation of proinflammatory M1-like resident macrophages in the liver and fat, characterized by increased CD38 expression and NADase activity. These CD38-overexpressing M1-like macrophages are activated by inflammatory cytokines secreted by senescent cells. Aging macrophages also exhibit impaired de novo NAD+ synthesis, further impacting their function.

Proinflammatory M1-like macrophages, along with senescent cells, may be major sources of proinflammatory cytokines in aging tissues, contributing to inflammaging. Aging is associated with increased NLRP3 inflammasome activation and IL-1β expression, driving a vicious cycle of inflammaging, tissue and DNA damage, activation of NAD+ consumers like CD38 and PARPs, and accelerated age-related decline.

Targeting macrophage immunometabolism, particularly NAD+ pathways, could be a therapeutic strategy to regulate macrophage function and polarization, relevant to inflammaging, neurodegenerative and autoinflammatory diseases, and cancer.

Adaptive Immunity and NAD+

Aging impairs adaptive immunity, termed immunosenescence, reducing the ability to mount effective immune responses due to altered adaptive immune cell function. Aging leads to immune cell population imbalances, including decreased naive T and B cells, loss of T cell antigen receptor diversity, and increased virtual memory T cells. NAD+ and NAD+-consuming enzymes regulate T cell biology, but their contribution to adaptive immunity aging is largely uncharacterized. Extracellular NAD+ may act as a danger signal, inducing cell death in regulatory T cell subpopulations. NAD+ also exhibits immunomodulatory properties, influencing T cell polarization. However, whether NAD+ promotes specific T cell phenotypes and whether NAD+ precursor manipulation can modulate immunity remains unclear.

A hallmark of adaptive immune aging is the expansion of highly cytotoxic CD8+CD28− memory T cells, characterized by high granzyme B secretion. This population exhibits decreased SIRT1 and FOXO1 levels, leading to enhanced glycolysis and granzyme B production. This highlights the potential of metabolic reprogramming via NAD+-associated pathways in age-related adaptive immune dysfunction. Upregulation of the NAD+–SIRT1–FOXO1 axis via CD38 inhibition increases effector functions in T helper 1 and 17 hybrid cells, suggesting potential therapeutic applications of CD38 inhibitors or NAD+ precursors in aging adaptive immunity.

Another feature of adaptive immune aging is the increase in exhausted T cells, expressing inhibitory receptors (PD1, TIM3), with decreased proliferation and effector functions. PD1 blockade, used in cancer immunotherapy, has been proposed to restore aged T cell effector function. CD38 overexpression is linked to dysfunctional and exhausted CD8 T cells in PD1 blockade-resistant cancers, suggesting potential benefits of CD38 inhibition for age-related T cell exhaustion. However, this hypothesis requires further investigation to determine the preclinical efficacy and safety of manipulating NAD+ levels to reverse age-related immunological dysfunction in adaptive immunity.

Cellular Senescence and NAD+

During aging, cells exposed to stress undergo cellular senescence, an essentially irreversible cell cycle arrest. A major feature of senescent cells is the senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP), characterized by increased inflammatory mediators (cytokines, chemokines). SASP contributes to impaired tissue homeostasis, stem cell regeneration, tissue repair, and inflammaging. Senescent cell accumulation with age is linked to age-associated diseases, and senolytic drugs that clear senescent cells may be effective treatments for conditions like Alzheimer’s disease. Boosting cellular NAD+ levels is also a promising target for extending healthspan, but NAD+’s impact on cellular senescence is complex. Senescent cells upregulate NAMPT expression, and SASP depends on NAD+ levels. NMN treatment can heighten SASP, potentially increasing chronic inflammation and promoting inflammation-driven cancers. This suggests NAD+-boosting supplements like NR and NMN may have long-term side effects, such as exacerbating chronic inflammation and cancer development. Further research is needed to understand the benefits and side effects of boosting NAD+ levels and how NAD+ metabolism impacts inflammatory immune and senescent cell biology.

Despite senescent cell accumulation in aging tissues and NAD+ decline, direct links between inflammatory senescent cell accumulation and NAD+ levels during aging were lacking. Recent findings show CD38 levels increase in aging mammalian tissues, potentially being a major NAD+-consuming enzyme responsible for age-related NAD+ decline. However, the mechanisms driving increased CD38 expression in aged tissues and the cells expressing CD38 were unclear. Recent observations suggest innate immune cells, especially macrophages, may respond to SASP with NAD+ degradation, contributing to organism-wide NAD+ decline. Macrophages co-cultured with or exposed to conditioned media from senescent cells exhibit enhanced CD38 expression and increased proliferation. Senescent cells and SASP activate CD38 expression and promote CD38-dependent NADase activity in macrophages. Aging mouse models and doxorubicin-treated mice show senescent cell accumulation in metabolic tissues (visceral fat, liver) directly activating CD38 expression in tissue-resident macrophages. Further supporting the link between inflammaging, senescent cell burden, and NAD+, mitochondrial dysfunction in cells initiates a proinflammatory program with cytokine secretion, associated with increased senescent cell burden, metabolic and physical dysfunction, and premature aging. NR supplementation partially rescued this multimorbidity syndrome by reducing inflammation and senescent cell burden, contrasting with findings that NAD+ precursors can increase SASP expression. Thus, NAD+’s regulation of senescence is complex and context-dependent.

These findings suggest targeting immune cells like T cells, macrophages, and senescent cells should be considered in strategies to restore NAD+ levels during aging. However, caution is warranted until more is known about the long-term side effects of enhancing NAD+ levels.

Neurodegeneration and NAD+

Aging is strongly associated with most neurodegenerative diseases and decreased brain NAD+ levels. NAD+ depletion is observed in accelerated aging models with neurodegeneration and neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and ALS. The causes and mechanisms of NAD+ loss in the aging brain are largely unknown, but evidence supports a neuroprotective role for NAD+.

Axonal degeneration, a precursor to many age-related neuronal disorders, is characterized by rapid NAD+ depletion. NMNAT2, an NAD+ biosynthetic enzyme, is a survival factor in axons, requiring constant replenishment via axonal transport. During axonal degeneration, NMNAT2 transport is blocked, and axonal NMNAT2 is degraded, leading to critical NAD+ depletion. SARM1, an NAD+-consuming enzyme, is activated by axonal injury and mediates axonal degeneration by promoting NAD+ degradation. *Wld*s mice, protected from axonal degeneration, lack SARM1 expression and have higher neuronal NAD+ levels due to NMNAT1 overexpression and redistribution to axons. Sarm1-knockout mice are also protected from axonal degeneration and rescue axon growth defects caused by NMNAT2 deficiency. Overexpressing a dominant negative SARM1 in neurons delays axon degeneration, suggesting therapeutic potential for targeting SARM1 in neuropathies.

*Wld*s mouse studies highlight the neuroprotective function of NMNAT1, NMNAT2, and NMNAT3 and their protective role in neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s disease. However, the precise mechanisms remain unclear. Besides SARM1-dependent NAD+ degradation, NMNATs may protect axons by degrading their substrate, the NAD+ precursor NMN. NMN itself has been reported to be neurotoxic, promoting SARM1 activation and axonal destruction. However, this evidence is controversial and requires validation. This raises questions about the therapeutic potential of increasing NAD+ synthesis via NMN supplementation.

Further evidence for NAD+’s neuroprotective role comes from studies using P7C3, a NAMPT activator. P7C3 is neuroprotective in mouse models of Parkinson’s, Alzheimer’s, and ALS. Other NAD+-consuming enzymes besides SARM1 contribute to intracellular NAD+ depletion in neurodegenerative diseases. CD38 expression increases in Alzheimer’s disease progression, and Cd38-knockout Alzheimer’s mice with elevated brain NAD+ exhibit milder disease phenotypes. Cd38-knockout mice are also protected from neuronal cell death after ischemic brain injury. Brain cells, including microglia, astrocytes, neurons, and endothelial cells, express CD38, and inflammatory cytokines induce CD38 expression in microglia and astrocytes. CD38 expression is associated with neuroinflammation and increased proinflammatory macrophages/microglia in mouse brains. CD38 also affects social behavior, as does its homolog CD157, substantiating NAD+’s functional impact on neuronal function. While direct causal roles for CD38 in neurodegenerative diseases are still being investigated, CD38 is emerging as a key enzyme in inflammaging and senescence, strongly linked to neurodegenerative diseases. PARP1 activation is also associated with Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s pathogenesis. PARP1 loss protects against brain dysfunction and cognitive decline in Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s models. However, PARP1 activation’s contribution to NAD+ depletion during neurodegeneration is largely unexplored.

Growing evidence indicates NAD+ is central to maintaining a healthy nervous system and impacts multiple brain cell types. Counteracting age-related NAD+ decline may be a viable therapeutic approach for neurodegenerative diseases. Restoring NAD+ levels via NAD+ supplements and NAMPT/NMNAT1 overexpression prevents axon degeneration. NAD+ precursors NR and NMN improve neuronal cell health, memory, and cognitive function in Alzheimer’s rat and mouse models and show neuroprotective properties in Drosophila Parkinson’s models and mouse ALS models. Several clinical trials are underway using NAD+ precursors, especially NR, to treat neurological disorders and promote healthy aging. These trials will expand our understanding of NAD+ metabolism in human neurodegenerative processes.

Table 2 |.

Human clinical trials focusing on ageing

| NAD+ precursor | Description | Design | Dose and duration | NCT/UMIN no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NMN | Study of efficacy against insulin sensitivity and β- cell functions in elderly women | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studyPostmenopausal and prediabetic womenAge 55–75 years | Oral administrationLong-term NMN administration: 250 mg daily for 8 weeks | NCT03151239 |

| Study of pharmacokinetics and safety in healthy volunteer | Non-randomized, open-label, non-placebo-controlled studyMale healthy volunteersAge from 40 to 60 years | Oral administrationSingle administration of 100, 250 or 500 mg NMN | UMIN000021309 | |

| Study of pharmacokinetics, safety and effects with regard to various hormonal levels in healthy volunteers | Randomized, dose-comparison, double-blinded studyHealthy volunteersAge from 50 to 70 years | Oral administrationLong-term NMN administration: 100 mg or 200 mg for 24 weeks | UMIN000025739 | |

| Study of pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy with regard to glucose metabolism in healthy volunteers | Non-randomized, open-label, non-placebo controlled studyMale healthy volunteersAge from 40 to 60 years | Oral administrationLong-term NMN administration for 8 weeks. Dose is not described | UMIN000030609 | |

| Study of pharmacokinetics, safety and efficacy with regard to blood pressure and physical endurance in healthy volunteers | Multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyHealthy volunteers Age from 40 to 65 years | Oral administrationLong term NMN administration; 300 mg daily for 60 days | NCT04228640 | |

| Nicotinamide riboside | Study of safety and efficacy with regard to physical activities in elderly people | Non-randomized, open-label, crossover studyHealthy volunteersAge from 55 to 79 years | Oral administrationCrossover of placebo for 6 weeks and NR 500 mg twice daily for 6 weeks | NCT02921659 |

| Study of efficacy with regard to bone, skeletal muscle and metabolic functions in ageing | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyFemale healthy volunteersAge from 65 to 80 years | Oral administration1,000 mg NR daily in a regimen of 500 mg every 12 hours for 4.5 months After 4.5 months, advanced individual training will be implemented with administration of 1,000 mg daily (500 mg every 12 hours) for a further 6 weeks. Total of 6 months | NCT03818802 | |

| Study of efficacy with regard to elevated systolic blood pressure and arterial stiffness in middle-aged and older adults | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studyHealthy volunteersAge from 50 to 79 years | Oral administrationLong-term NR administration: 1,000 mg daily for 3 months | NCT03821623 | |

| Study of recovery phase and improved outcome after acute illness | Randomized studyHospitalized patients with tissue damageAge from 18 years | Oral administrationLong-term NR administration: 250, 500 or 1,000 mg daily for 3 months | NCT04110028 | |

| Study of pharmacokinetics and efficacy with regard to brain function, including cognition and blood flow in people with MCI | Randomized study Patients with MCI Age from 65 years | Oral administrationNR dosage increased from 250 mg daily to 1 g daily as tolerated | NCT02942888 | |

| Study of cognitive performance in subjective cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment in ageing | Crossover, randomized block sequence, double-blind, placebo-controlled studyPatients with MCIAge from 60 years | Oral administrationLong-term NR administration: 1,200 mg for 8 weeks | NCT04078178 | |

| Study of safety and efficacy with regard to NAD+ sustainability in elderly people | Randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind studyHealthy volunteersAge from 60 to 80 years | Oral administration1XNRPT (250 mg NR and 50 mg pterostilbene) once daily or 2XNRPT (500 mg NR and 100 mg pterostilbene) twice daily for 8 weeks | NCT02678611 | |

| NAM | Study of the efficacy a mixture of the NAD+ precursors NA, NAM and tryptophan with regard to physical function and skeletal muscle mitochondrial function in physically compromised, elderly humans | Randomized, double-blind, crossover trialHealthy volunteersAge from 65 to 75 years | Oral administrationLong-term administration of NAD+ precursors: total of 204 NE per serving in a whey protein source for 31 days | NCT03310034 |

| Exploratory study on phosphorylated tau protein changes in CSF in mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease and mild Alzheimer disease dementia | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled studyPatients with Alzheimer diseaseAge from 50 years | Oral administrationLong-term administration of NAM: 1,500 mg daily for 48 weeks | NCT03061474 | |

| Study of efficacy with regard to the severity of Parkinson disease symptoms | Double-blind, randomized study Patients with Parkinson disease Age from 35 years | Oral administrationLong-term administration of NAM: 200 mg daily for 18 months | NCT03808961 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; NA, nicotinic acid; NAD+, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; NAM, nicotinamide; NE, niacin equivalents; NMN, nicotinamide mononucleotide; NR, nicotinamide riboside.

Fig. 3 |. NAD+ metabolism in ageing.

A | Decreased nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) levels have been implicated in various processes associated with ageing (see also Supplementary Box 2). Aa | Ageing is associated with aberrant proinflammatory immune cell activation or ‘inflammageing’, leading to sustained low-grade inflammation. This is caused in part by the accumulation of senescent cells, which via a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP) promote the phenotypic polarization of macrophages towards a proinflammatory M1 state, thereby driving inflammation. There is evidence that in response to the SASP in these macrophages expression of the NAD+-consuming enzymes CD38 and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs) increases, leading to NAD+ level decline, and that these mechanisms importantly contribute to the decrease of NAD+ levels in ageing. In addition, it has been shown that in aged T cells mitochondrial function declines, and this leads to increased secretion of proinflammatory cytokines that promote the state of inflammation and also induce senescence. Ab | Axonal degeneration, which is a precursor to many age-related neuronal disorders, is characterized by rapid NAD+ depletion. During normal physiological conditions, NAD+ biosynthetic enzymes, nicotinamide mononucleotide adenylyltransferases (NMNATs), are protective against axonal degeneration, and their expression supports maintenance of axons and prevents neurodegeneration. In particular, NMNAT2 is an important survival factor in axons, to which it needs to be constantly delivered from the soma — where it is synthesized — to account for its rapid turnover, and these transport processes are disturbed during axonal degeneration. Moreover, the NAD+-consuming enzyme SARM1 is activated by axonal injury and mediates axonal degeneration by promoting NAD+ degradation. Ac | Autophagy is a key cellular catabolic process that allows cells to adapt to variable nutrient availability and serves in cellular quality control, allowing removal of defective organelles and proteins. Autophagy is regulated downstream of NAD+ levels via sirtuins (mostly SIRT1). Decline of NAD+ levels reduces overall autophagic flux as well as selective removal of mitochondria via mitophagy, suggesting that defective autophagy can be a consequence of NAD+ depletion during ageing, contributing to cell dysfunction. B | Because NAD+ is a cofactor for various enzymes, loss of NAD+ impacts a plethora of cellular processes. For example, NAD+ is required for the activity of epigenetic regulators such as SIRT1, and decline in its level causes changes in histone modifications, thereby affecting chromatin organization and function in gene expression. There is evidence that the ageing-associated loss of NAD+ is related to increased expression of PARPs, which can be caused by increased levels of DNA damage and the need for DNA repair during ageing (panel Ba). NAD+ also affects transcriptional activity of the core clock components CLOCK and BMAL, thereby regulating circadian expression of important metabolic genes as well as nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), which in turn is required for circadian oscillation in NAD+ levels (panel Bb). Decreased NAD+ levels also interfere with the activity of PARPs and sirtuins in DNA repair, leading to genomic instability: a hallmark of ageing and cancer (panel Bc). ADPR, ADP-ribose; ATG, autophagy-related protein; FOXO, forkhead box protein O; ROS, reactive oxygen species.

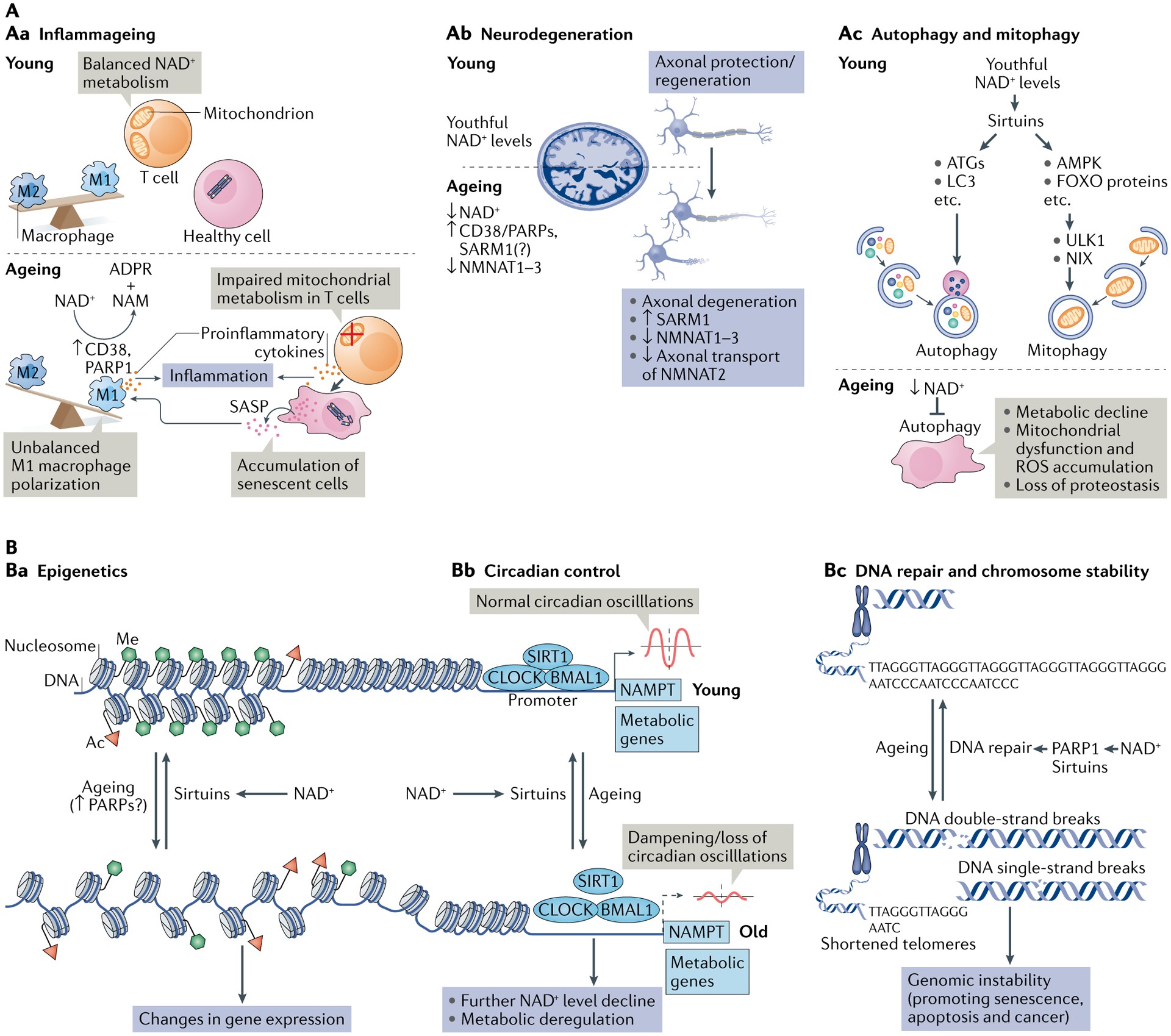

Therapeutic Targeting of NAD+ Level Decline: Dietary Supplementation, Biosynthesis Modulation, and Consumption Inhibition

Over the past two decades, NAD+’s crucial role in healthy aging and longevity has become increasingly evident. Preclinical studies across various models, from C. elegans and Drosophila to rodents and human cells, have firmly established an age-dependent decline in NAD+ levels, ranging from 10% to 65% depending on the organ and age. NAD+ levels can be influenced by dietary and lifestyle choices FIG. 4 and modulated pharmacologically. Three main therapeutic approaches to increase NAD+ levels are being explored:

- Dietary supplementation with NAD+ precursors: Utilizing precursors involved in NAD+ salvage pathways.

- Modulation of NAD+ biosynthetic enzymes: Targeting enzymes regulating rate-limiting steps in de novo synthesis and salvage pathways (ACMSD and NAMPT, respectively).

- Inhibition of NAD+ degradation enzymes: Blocking enzymes like PARPs and CD38.

Augmenting NAD+ levels has shown efficacy in various mouse models of human diseases TABLE 1, leading to numerous clinical trials of NAD+ boosters in humans during aging TABLE 2. While this review will not detail these clinical trials extensively, readers are directed to comprehensive reviews on this topic.

Preclinical rodent studies suggest strong translational potential for NAD+-boosting therapies. Human studies are less advanced, with initial clinical trials primarily demonstrating the safety and pharmacokinetic properties of NAD+ precursors. NMN and NR administration has been shown to be safe and effectively increase NAD+ levels in healthy volunteers TABLE 2. Phase I clinical trials have been more prevalent for NR than NMN, with mixed results. Some trials show short-term NR benefits in healthy elderly individuals and positive outcomes in ALS patients. However, NR has shown limited efficacy in aged obese men. Further human clinical studies are needed to determine optimal doses, treatment durations, long-term toxicity, and to consider participant diversity for better translation of NAD+-boosting strategies.

Dietary Supplementation with NAD+ Precursors

The effects of different NAD+ precursors on lifespan and healthspan have been extensively studied in yeast and C. elegans. Low micromolar concentrations of NR extend lifespan in both wild-type yeast and C. elegans in a sirtuin-dependent manner. NAM administration also extended lifespan in wild-type C. elegans. However, supraphysiologic NAM doses (1–5 mM) have been associated with reduced lifespan in yeast and C. elegans. The beneficial or detrimental effects of NAM in aging remain unclear. This discrepancy may be due to NAM’s direct and indirect influences on NAD+ function. Besides being an NAD+ precursor, NAM is a byproduct of NAD+ catabolism, and high millimolar concentrations can act as a feedback inhibitor of NAD+-dependent enzymes like PARPs and sirtuins in vitro. However, the inhibitory effects of high-dose NAM were inconclusive in some animal studies. Another potential inhibitory mechanism involves increased NAM methylation at high doses, affecting methyl group availability for DNA methylation and gene expression. High levels of methylated NAM have been linked to type 2 diabetes, Parkinson’s, and cardiac diseases. Further studies are needed to determine safe NAM doses and treatment durations.

NAD+-boosting strategies using NR and/or NMN have also been effective in delaying progeroid phenotypes and extending lifespan in C. elegans models of xeroderma pigmentosum group A, ataxia telangiectasia, Cockayne syndrome, and Werner syndrome. NMN treatment significantly increased NAD+ levels and maximum lifespan in a mouse model of ataxia telangiectasia. NR treatment improved muscle stem cell function by regulating mitochondrial metabolism in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy.

Few studies have investigated the effects of NMN, NAM, and NR on prolonging healthspan and/or lifespan in wild-type mice. Long-term (1-year) NMN feeding in mice starting at 5 months increased insulin sensitivity, energy metabolism, physical activity, and improved lipid profiles without obvious toxicity. Long-term NAM administration prevented high-fat diet-related disease and promoted healthspan but did not significantly extend lifespan. NR administration in old mice showed a small but significant (5%) lifespan increase. Most preclinical studies using NAD+ precursors have focused on extending healthspan by counteracting age-related diseases characterized by NAD+ decline TABLE 1. NMN enhances mitochondrial function in various organs, including skeletal muscle, kidney, liver, heart, eyes, brain, and the cardiovascular system, and mitigates oxidative stress in the vasculature, including improvements in neurovascular coupling in the aged cortex. These NMN effects may be mediated by sirtuins, for example, SIRT3 mediates NMN-induced improvements in cardiac and metabolic function in cardiomyopathy models. NMN supplementation also increased endothelial cell number and improved endothelial function, blood flow, and endurance in elderly mice via a SIRT1-dependent mechanism.

Reduced NR (NRH) is more stable and potent than NR in increasing intracellular NAD+ content, acting through a new metabolic pathway where adenosine kinase converts NRH to NMNH, which is oxidized to NMN or further metabolized to NADH and NAD+. Future studies are needed to compare the efficacy of NRH relative to NAM, NR, and NMN and assess potential side effects.