Wolves are renowned for their adaptability and resilience, traits that are particularly evident in their feeding habits. Their diet is far from fixed, changing significantly based on their environment and the availability of prey. This flexibility is crucial for their survival, especially in regions where their primary food sources become scarce. Understanding What Do Wolves Eat reveals fascinating insights into their ecological role and survival strategies.

Wolf eating prey in a natural habitat, illustrating the flexibility of wolf diets in diverse environments.

Wolf eating prey in a natural habitat, illustrating the flexibility of wolf diets in diverse environments.

Wolves and Ungulate Prey: The Traditional View

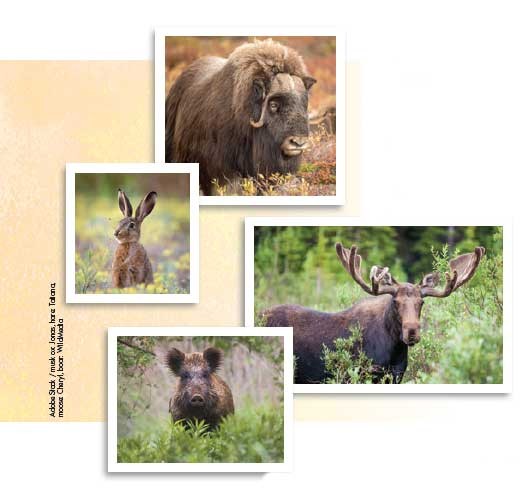

For a long time, the relationship between wolves and their prey has been studied extensively, with ungulates like moose and deer often considered their primary food source. The classic study on Isle Royale, spanning over half a century, provides a compelling example of this predator-prey dynamic. From 1959 to 1980, researchers observed a cyclical pattern between moose and wolf populations. Abundant moose meant more food for wolves, leading to better nutrition, increased pup survival, and a growing wolf population. However, a larger wolf population eventually caused a decline in moose numbers, reducing the food available for wolves and subsequently decreasing their population. As wolf numbers fell, the pressure on moose lessened, allowing their population to rebound, restarting the cycle. This long-term study highlights how prey availability can directly influence wolf populations. Yet, it’s important to remember that even in seemingly simple ecosystems, other factors like diseases, parasites, and genetic factors can complicate these predator-prey relationships.

Prey Switching: Adapting to Changing Prey Availability

The dynamics of what wolves eat become even more complex in environments where multiple prey species are present. In these diverse ecosystems, when a primary prey species declines, wolves exhibit a behavior known as “prey switching.” This means they adapt by shifting their diet to other available prey. This adaptation allows wolf populations to persist even when their preferred food source becomes scarce.

A study in the east-central Superior National Forest in northeastern Minnesota illustrates this prey switching behavior effectively. This region is home to white-tailed deer, moose, and beavers, all of which are important food sources for wolves. Between 2006 and 2016, the moose population in this area experienced a significant decline, dropping by more than half. To investigate the impact on wolves, researchers compared wolf populations before and after this moose decline. They tracked radio-collared wolves and analyzed wolf scat to understand their dietary changes. Surprisingly, instead of declining with the moose population, the wolf population nearly doubled. The analysis of wolf scat revealed that wolves had compensated for the lack of moose by increasing their hunting of white-tailed deer. Interestingly, they continued to prey on moose calves, which unfortunately contributed to the ongoing decline of the moose population. It was only when the white-tailed deer population also began to decrease that the wolf population finally started to decline, demonstrating the wolves’ reliance on available prey and their ability to switch food sources when necessary.

The Surprising Diet of Alaskan Wolves: Beyond Ungulates

Further research into what do wolves eat in different geographical locations reveals even greater dietary flexibility. A recent study focused on wolves inhabiting the Alexander Archipelago and the southeastern mainland of Alaska, regions where ungulates can be scarce or absent. From 2012 to 2018, researchers collected a large number of wolf scats – 860 in total – from twelve different study sites to analyze their diet. DNA analysis of these scats identified an astonishing 55 different food sources. While the study confirmed that ungulates, such as moose and deer, constituted a significant portion of their diet (approximately 65% regionally), it also highlighted considerable variation in the type and proportion of ungulates consumed depending on the specific location. For example, mainland wolves primarily preyed on moose and mountain goats, while island wolves relied more heavily on Sitka black-tailed deer. Crucially, the study demonstrated that when these primary ungulate prey species became less available, Alaskan wolves didn’t just switch to one or two alternative prey types, but broadened their dietary niche considerably. They incorporated a wide variety of species, including land mammals like beaver, black bear, and rodents, marine life including marine mammals and fish, and even birds, showcasing an exceptional level of dietary adaptability.

Coastal Wolves of Gustavus: An Exceptionally Varied Menu

In some locations, ungulates are not even the primary component of a wolf’s diet. The wolves living near Gustavus, on the Alaskan mainland coast, exhibit perhaps the most diverse diet studied. In this area, moose made up only 28% of their diet. Remarkably, sea mammals, predominantly sea otters, constituted 22% of their food intake. Black bears represented another 11%, and seasonally available salmon made up 10% of their diet. Researchers suggest that these wolves opt for these diverse prey sources because they are often safer and easier to hunt than larger ungulates like moose. Furthermore, the mild coastal climate in Gustavus allows for year-round hunting and scavenging of marine mammals along the shoreline, providing a consistent alternative food supply.

In conclusion, what wolves eat is far from a simple question with a straightforward answer. Wolves are opportunistic and adaptable predators whose diets are shaped by their environment and the availability of prey. From the cyclical relationship with ungulates in some regions to the diverse and surprising diets of Alaskan coastal wolves, their feeding habits demonstrate a remarkable flexibility that is key to their survival in a wide range of ecosystems.