When Drake condescendingly told Metro Boomin to “make some drums” during their feud with Kendrick Lamar, the superproducer did just that, but with a twist. The result, a track titled “BBL Drizzy,” not only went viral but also highlighted a significant shift in music production: the rise of AI.

The beat of “BBL Drizzy” features a soulful, vintage-sounding vocal sample layered over hard-hitting 808 drums. Metro Boomin released it on SoundCloud on May 5th, inviting fans to rap over it for a chance to win a free beat. The track quickly gained traction, but the story behind the vocals soon became the real headline.

It turned out that the captivating voice on “BBL Drizzy” wasn’t from a human singer at all. It was generated by artificial intelligence. The entire vocal track, including the melody and the instrumental sample, was created using Udio, an AI music startup founded by former Google DeepMind engineers. While Metro Boomin himself wasn’t initially aware of the AI origin of the track, his playful diss inadvertently became a landmark moment, showcasing the potential of AI-generated sampling in music production. (Representatives for Metro Boomin did not respond to Billboard’s requests for comment).

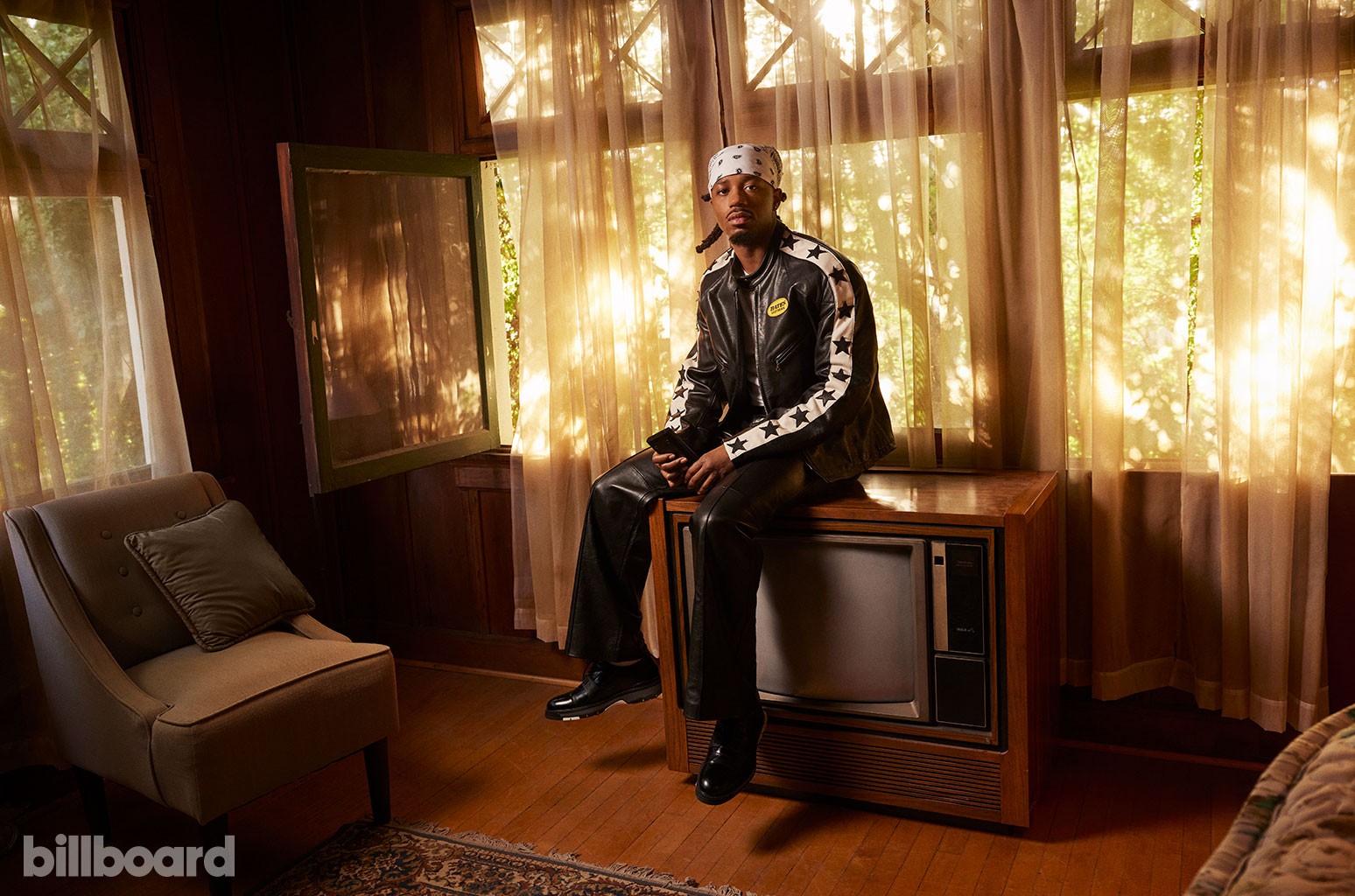

While the “BBL Drizzy” track is AI-generated, it was still prompted by human creativity. King Willonius, a comedian, musician, and content creator, used Udio to create the song on April 14th. His inspiration came from a tweet by Rick Ross, who jokingly suggested that Drake had gotten a Brazilian Butt Lift (BBL). This humorous jab provided the lyrical theme for the AI-generated song. “I think it’s a misconception that people think AI wrote ‘BBL Drizzy’,” Willonius explained to Billboard. “There’s no way AI could write lyrics like ‘I’m thicker than a Snicker and I got the best BBL in history,’” he added with a laugh, emphasizing the human element behind the track’s comedic and viral nature.

The emergence of AI sampling, as exemplified by “BBL Drizzy,” opens up a Pandora’s Box of questions concerning the music industry. Legal, philosophical, cultural, and technical challenges need to be addressed before AI sampling becomes mainstream. However, it’s easy to envision a future where producers routinely use AI to create vintage-sounding samples, especially given the notoriously complex and time-consuming process of clearing traditional samples. Even for established producers like Metro Boomin, sample clearance can be a hurdle.

“If people on the other side [of sample clearance negotiations] know they’re probably going to make money on the new song, like with a Metro Boomin-level artist, they will make it a priority to clear a sample quickly, but that’s not how it is for everyone,” notes Todd Rubenstein, a music attorney and founder of Todd Rubenstein Law. Grammy-winning writer/producer Oak Felder echoes this sentiment, stating, “I’ll be honest, I’m dealing with a tough clearance right now, and I’ve dealt with it before. I had trouble clearing an Annie Lennox sample for a Nicki Minaj record once… It’s hard.”

For smaller producers, sampling established songs often feels legally prohibitive. While some proceed without permission, risking legal repercussions, others avoid sampling altogether. The case of bedroom producer Young Kio, who sampled an undisclosed Nine Inch Nails song in a beat that became Lil Nas X’s massive hit “Old Town Road,” illustrates the potential legal pitfalls. The discovery of the sample forced Lil Nas X to concede a significant portion of publishing and master royalties.

David Ding, co-founder of Udio, believes AI samples could offer a solution to these rights management complexities. He explains that Udio’s AI model excels at creating realistic songs reminiscent of “Motown ‘70s soul,” a genre frequently sampled in hip-hop, as well as classical and electronic music. “It’s a wide-ranging model,” Ding states.

King Willonius sees AI samples as a tool for musicians to react quickly in today’s fast-paced news cycle. While he has created original songs before, AI enabled him to respond in real-time to the Drake-Kendrick Lamar feud. “I never could’ve done that without AI tools,” he says. Evan Bogart, a Grammy-winning songwriter and founder of Seeker Music, compares AI sampling to digital crate digging. “I think it’s super cool to use AI in this way,” he says. “It’s good for when you dig and can’t find the right fit. Now, you can also try to just generate new ideas that sound like old soul samples.”

AI sampling also presents a potential way to avoid the substantial financial burdens associated with traditional sampling. Ariana Grande, for example, reportedly ceded 90% of her publishing income for “7 Rings” to the writers of “My Favorite Things” due to the interpolation of the melody. This highlights the significant costs, even for interpolations, let alone full samples.

“It certainly could help you having to avoid paying other people and avoid the hassle,” says Rubenstein regarding AI sampling’s financial benefits. However, he cautions users to carefully review the terms of service of AI models, emphasizing the need to understand how these AI systems are trained.

Many AI music models are trained on copyrighted material without the consent or compensation of rights holders, a practice widely criticized within the music industry. While AI companies argue “fair use,” the legality is still under legal scrutiny. Lawsuits, such as The New York Times v. OpenAI and UMG et al. v. Anthropic, challenge the use of copyrighted material in AI training. Rep. Adam Schiff has even introduced the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act to promote transparency in AI training data.

Udio’s terms of service place the onus on users regarding copyright infringement, requiring them to indemnify the company against any claims arising from the use of AI-generated works. When questioned about the training data, Udio co-founder Ding remained vague, stating, “We can’t reveal the exact source of our training data. We train our model on publicly available data that we obtained from the internet. It’s basically, like, we train the model on good music just like how human musicians would listen to music.” He declined to comment further on copyright issues.

Diaa El All, CEO/founder of Soundful, another AI music company, believes AI can simplify rights management if implemented ethically. Soundful is certified by Fairly Trained, ensuring no copyrighted material is used in training without consent. El All highlights that developing novel AI sampling methods is a key focus for Soundful, and they are collaborating with an artist to create AI models inspired by specific pre-existing works, with proper clearances obtained.

Despite the potential of AI sampling, Oak Felder and Evan Bogart believe it won’t entirely replace traditional sampling. The nostalgia and familiarity that samples evoke hold significant appeal. AI-generated originals cannot replicate this specific emotional connection.

“BBL Drizzy,” though initially conceived as a joke, has significant implications. Felder considers it a pivotal moment, stating, “I think this is very important. This is one of the first successful uses [AI sampling] on a commercial level, but in a year’s time, there’s going to be 1,000 of these. Well, I bet there’s already a thousand of these now.” The track serves as a potent example of AI’s growing influence on music creation and the complex questions it raises for the future of the industry.