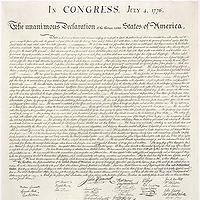

1776 stands as a monumental year in American history, primarily recognized for the adoption of the Declaration of Independence. This landmark document, endorsed by the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, officially declared that the 13 American colonies were severing their political ties with Great Britain. This bold move was not just a statement of separation; it was a comprehensive articulation of the colonists’ reasons for seeking autonomy. By proclaiming themselves an independent nation, the American colonists strategically positioned themselves to secure a formal alliance with France, a crucial step that would provide them with much-needed French assistance in their fight against Great Britain.

Background to Independence: Growing Tensions

The seeds of the events of 1776 were sown in the preceding decades. Throughout the 1760s and early 1770s, a palpable discord grew between the North American colonists and British imperial policies. Friction points were numerous, but prominently featured were issues of taxation and frontier policy. The colonists felt increasingly aggrieved by what they considered unjust taxation measures imposed by the British Parliament without colonial representation, and they also clashed with British frontier policies that restricted westward expansion.

Repeated appeals and protests from the colonists aimed at influencing British policies proved futile. Instead of yielding to colonial concerns, the British government responded with increasingly stringent measures, including the closure of the port of Boston and the imposition of martial law in Massachusetts. In response to these escalating tensions, the colonial governments convened the Continental Congress. Initially, the Congress aimed to coordinate a unified colonial boycott of British goods as a means of economic pressure. However, as confrontations between American colonists and British forces erupted in Massachusetts, the Continental Congress broadened its role. Leveraging local groups, originally formed to enforce the boycott, the Congress began to coordinate broader resistance efforts against the British military presence. Across the colonies, British officials witnessed their authority progressively challenged by burgeoning informal local governments, even as pockets of loyalist sentiment persisted in certain regions.

The Path to Declaration: From Reconciliation to Independence

Despite the escalating conflict and the shift towards organized resistance, the prevailing sentiment among colonial leaders initially favored reconciliation with the British Government. Independence was not a universally embraced goal, and most members of the Continental Congress were hesitant to declare a complete break from Britain. However, by late 1775, a subtle but significant shift began to occur. Benjamin Franklin, serving on the Secret Committee of Correspondence, started to subtly suggest to French agents and other European sympathizers that the colonies were increasingly considering independence. While this may have reflected a growing reality, Franklin’s hints were also strategically intended to persuade the French to provide aid to the colonists. It was becoming clear that a declaration of independence would be a prerequisite for France to formally consider an alliance.

The winter of 1775–1776 proved to be a turning point. Members of the Continental Congress increasingly came to the realization that reconciliation with Britain was improbable, and that independence was the only viable path forward. A decisive moment arrived on December 22, 1775, when the British Parliament enacted a prohibition on trade with the colonies. The Continental Congress responded in April 1776 by opening colonial ports to trade—a clear act of defiance and a significant stride towards severing ties with Britain. Adding momentum to the cause of independence was the January 1776 publication of Thomas Paine’s influential pamphlet, Common Sense. Paine’s compelling arguments in favor of colonial independence resonated widely and were disseminated throughout the colonies, galvanizing public support for separation. By February 1776, colonial leaders were actively exploring the formation of foreign alliances and initiated the drafting of the Model Treaty, which would later form the foundation for the pivotal 1778 alliance with France. Advocates for independence understood the necessity of securing broad congressional support before formally bringing the momentous issue to a vote. On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee introduced a motion in Congress to declare independence. While some members felt certain colonies were not yet prepared for such a declaration, Congress acknowledged the gravity of the situation and formed a committee tasked with drafting a declaration of independence. This crucial responsibility was entrusted to Thomas Jefferson.

Drafting and Adoption of the Declaration

Thomas Jefferson undertook the drafting process, and his initial document was then reviewed by Benjamin Franklin and John Adams. While respecting Jefferson’s original composition, Franklin and Adams made strategic revisions. They removed passages that they anticipated would be contentious or meet with skepticism. Notably, these included sections that directly blamed King George III for the transatlantic slave trade and those that placed blame on the British people, rather than specifically on their government. The revised draft was presented to Congress by the committee on June 28, 1776. After further debate and refinement, the Continental Congress officially adopted the final text of the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776.

Immediate Aftermath and International Impact

The British Government initially attempted to downplay the significance of the Declaration, dismissing it as an inconsequential document produced by disgruntled colonists. British officials commissioned propagandists to publicly criticize the Declaration, highlighting perceived weaknesses and refuting the colonists’ grievances. Domestically, the Declaration created divisions within British opposition circles, with some American sympathizers believing it was too extreme. However, in British-ruled Ireland, the Declaration garnered considerable support.

Diplomatically, the Declaration of Independence had a profound and immediate effect, paving the way for the United States to be recognized by friendly foreign governments. The Sultan of Morocco made reference to American ships in a consular document in 1777, indicating early, informal recognition. However, formal recognition from a major European power came with the 1778 Treaty of Alliance with France, a direct consequence of the Declaration. The Netherlands formally acknowledged U.S. independence in 1782. Although Spain joined the war against Great Britain in 1779, they did not officially recognize U.S. independence until the 1783 Treaty of Paris. This treaty, which formally concluded the War of the American Revolution, included Great Britain’s official acknowledgment of the United States as a sovereign and independent nation, solidifying the declaration made in 1776.

In conclusion, 1776 was a transformative year defined by the bold step of declaring independence. The Declaration of Independence was not merely a statement of separation, but a catalyst that reshaped the political landscape, enabled crucial foreign alliances, and ultimately laid the foundation for the birth of a new nation.