In the realm of ecology, understanding how energy and nutrients flow through an ecosystem is paramount. While food chains offer a simplified linear pathway, the reality of nature is far more complex and interconnected. This is where the concept of a food web comes into play. A food web, also known as a food cycle, is an intricate network illustrating the feeding relationships between various organisms within an ecosystem. It’s a holistic representation that goes beyond the simplicity of a food chain, showcasing how different food chains intertwine and overlap to create a complex web of life.

Unlike a food chain that follows a single, linear sequence of “who eats whom,” a food web demonstrates that most organisms participate in multiple food chains. They may consume, and be consumed by, a variety of species. This interconnectedness is crucial for ecosystem stability and resilience. Think of a forest; a simple food chain might suggest that squirrels eat acorns and are eaten by foxes. However, a food web reveals a more accurate picture: squirrels also eat insects, fruits, and fungi, and they are preyed upon by hawks, owls, and even snakes, in addition to foxes. This intricate web of interactions ensures that if one food source declines or one predator population changes, the ecosystem is less likely to collapse because organisms have alternative food sources and predators.

Decoding the Structure of a Food Web

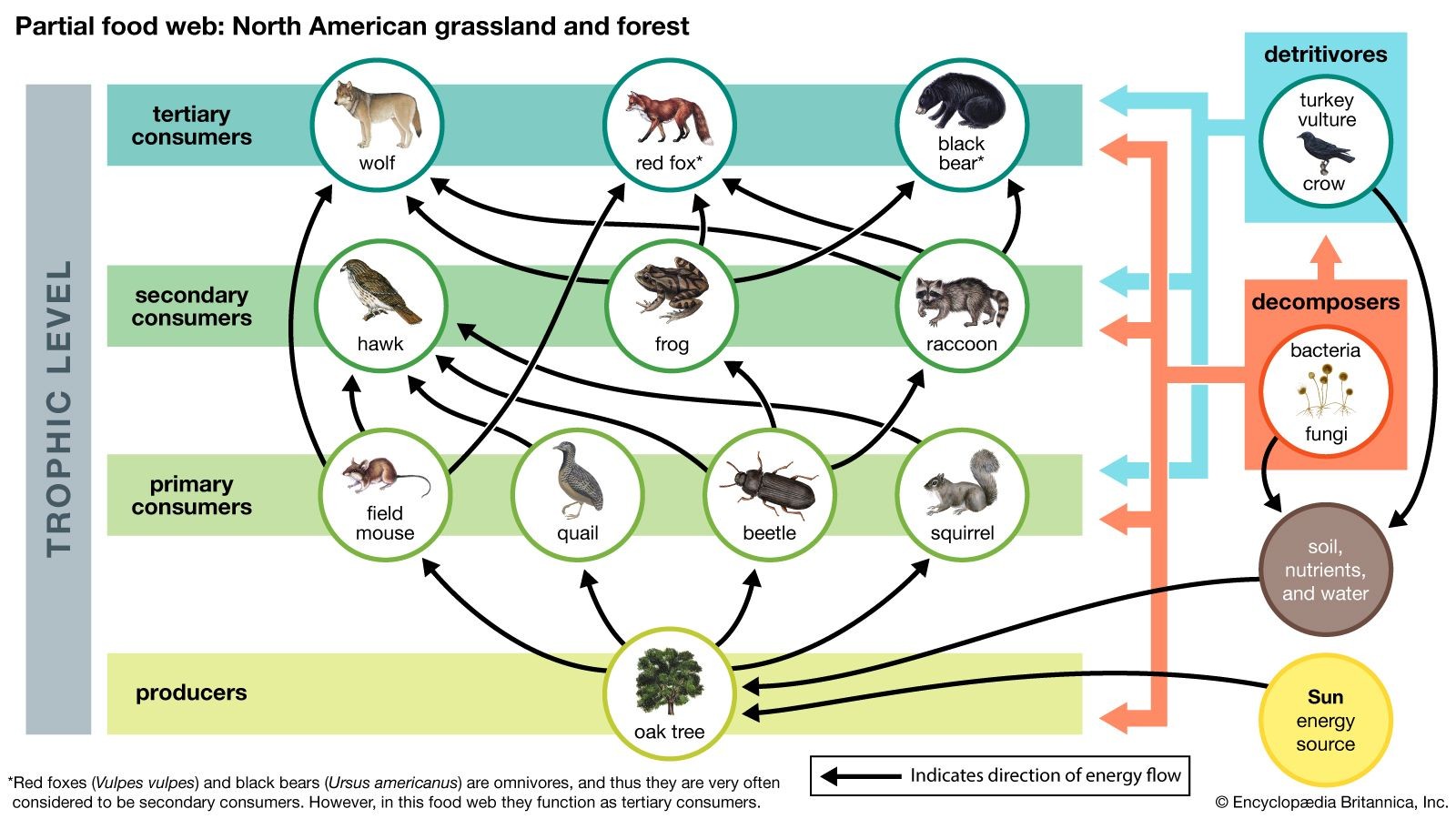

Food webs are structured around trophic levels, which represent an organism’s position in the feeding hierarchy. At the base of nearly all food webs (excluding those in deep caves or hydrothermal vents) is the sun, the ultimate source of energy. Organisms within a food web are broadly categorized into producers and consumers, reflecting their role in energy acquisition.

-

Producers (Autotrophs): These are the foundation of the food web. Producers, also known as autotrophs, are organisms that can produce their own food, typically through photosynthesis. Plants are the most recognizable producers on land, converting sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into energy-rich sugars. However, aquatic ecosystems rely on algae, phytoplankton, and other photosynthetic organisms as primary producers. A towering oak tree, for example, is a producer. Its leaves are consumed by insects and birds, while its acorns are a food source for squirrels and other mammals, initiating multiple pathways within the food web.

-

Consumers (Heterotrophs): Consumers, or heterotrophs, cannot produce their own food and must obtain energy by consuming other organisms. They are categorized into different levels based on their feeding habits:

- Primary Consumers (Herbivores): These organisms feed directly on producers. Herbivores are plant-eaters, such as leaf-eating insects, rabbits grazing on grass, or deer browsing on shrubs. However, omnivores, animals that eat both plants and animals, can also function as primary consumers if they primarily feed on plant matter.

- Secondary Consumers (Carnivores and Omnivores): Secondary consumers prey on primary consumers. This level includes carnivores, animals that primarily eat meat, and omnivores that incorporate both plants and animals into their diet. Examples include snakes that eat mice (primary consumers), spiders that trap insects, and predatory fish that consume smaller herbivorous fish.

- Tertiary Consumers (Apex Predators): At the top of the food web are tertiary consumers, often apex predators. These are carnivores that prey on secondary consumers and are not preyed upon by other animals in their ecosystem. Examples include wolves, lions, birds of prey like eagles, and sharks. They play a crucial role in regulating populations at lower trophic levels.

Beyond producers and consumers, food webs also include essential roles for detritivores and decomposers.

-

Detritivores: These are organisms that consume dead organic matter, known as detritus. Scavengers like vultures and beetles are detritivores, feeding on carcasses and decaying matter. They break down large pieces of organic material into smaller pieces.

-

Decomposers: Decomposers, primarily fungi and bacteria, complete the process of breaking down organic matter. They decompose dead organisms and waste into simpler inorganic compounds, such as nitrogen, carbon, calcium, and phosphorus. These nutrients are then returned to the soil and atmosphere, becoming available for producers to use, thus closing the nutrient cycle within the ecosystem.

These trophic levels can be visualized as an energy pyramid. Energy flows upwards through the food web, starting with the producers at the base. Each trophic level represents a step in the energy transfer. However, energy transfer is not efficient; a significant amount of energy is lost at each level, primarily as heat. This energy loss explains why food webs typically have fewer trophic levels at the top and why there are fewer apex predators compared to producers.

The Dynamic Interactions Within Food Webs

Food webs are not static representations; they are dynamic systems constantly changing due to various factors such as seasonal changes, population fluctuations, and environmental events. The beauty of a food web lies in its depiction of the complex and often overlapping feeding relationships.

Unlike simplified food chains, food webs illustrate that many organisms have diverse diets and play multiple roles. Omnivores, by their nature, occupy various trophic levels depending on what they are consuming. Even carnivores might occasionally consume plant matter or scavenge, adding to the complexity. The interconnectedness within a food web provides resilience to the ecosystem. If a particular species declines, other organisms have alternative food sources, preventing cascading effects that could destabilize the entire system.

Understanding food webs is crucial for comprehending the intricate balance of nature. They highlight the interdependence of species and the flow of energy and nutrients that sustain ecosystems. By studying food webs, ecologists can gain insights into ecosystem dynamics, predict the impacts of environmental changes, and develop effective conservation strategies to protect these vital networks of life.