The plot of a story is the backbone of any narrative, guiding readers through a carefully constructed sequence of events from beginning to end. Storytelling, in its diverse forms, has always relied on the power of plot to captivate and engage audiences. Whether you’re crafting a novel, screenplay, or short story, a solid understanding of plot structure and its various types is crucial for bringing your creative visions to life.

But what exactly is plot? How does it differ from the broader concept of “story”? What are the essential plot devices that writers use to create intrigue and surprise? And fundamentally, how does plot contribute to the overall narrative experience?

This article will delve into the definition of plot, explore different plot structures, examine essential plot elements, and uncover the vast possibilities of narrative organization.

Let’s begin by defining plot in detail.

Plot Definition: Unpacking the Essence of Story Plot

The plot of a story is defined as the intentional sequence of events that form a narrative. It’s not merely a list of happenings, but rather a carefully connected chain where each event is caused by or significantly influences the ones that follow. In essence, a story plot is a series of cause-and-effect relationships that shape the entire narrative arc.

What is plot?: A connected series of events, driven by cause and effect, that gives shape to a story.

It’s crucial to distinguish plot from a simple story summary. Plot necessitates causation. The renowned novelist E.M. Forster eloquently illustrated this distinction:

“’The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief,’ is a plot.” ― E.M. Forster

The addition of “of grief” is what transforms a mere sequence of events into a plot. It introduces causality. Without this element, the queen’s death could be attributed to countless reasons, rendering the sequence a simple chronicle rather than a plot-driven narrative. Furthermore, “grief” introduces a potential theme into the story, adding depth beyond the surface events.

Key Elements of Plot

To construct a compelling plot, certain essential elements must be present:

- Causation: This is the fundamental building block. Each event should logically lead to the next, creating a chain reaction of plot points that drive the story forward. This cause-and-effect relationship provides narrative momentum.

- Characters: Stories are fundamentally about people (or personified entities). A plot must introduce and develop characters, particularly the central figures who will experience and drive the unfolding events. Their actions, motivations, and relationships are integral to plot progression.

- Conflict: Conflict is the engine of plot. It arises from characters with opposing interests or internal struggles. Without conflict, there is no story to tell, no tension to resolve, and no thematic exploration. Conflict can be internal (character vs. self), external (character vs. character, character vs. society, character vs. nature), or a combination of both.

The interplay of these elements—causation, characters, and conflict—forms the very structure of a story. Let’s explore some common plot structures that writers utilize to organize these elements effectively.

Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot. — Leigh Brackett

Exploring Common Plot Structures

Throughout literary history, storytellers have experimented with countless ways to structure plots. Understanding these established plot structures can provide writers with valuable frameworks and solutions when developing their narratives. Consider these structures as potential blueprints for your own storytelling endeavors.

Aristotle’s Story Triangle: The Foundation of Narrative Structure

The earliest formal discussion of plot structure comes from Aristotle’s Poetics (circa 335 B.C.). Aristotle conceptualized plot as a narrative triangle, suggesting a linear progression of events that resolves conflicts in three distinct parts: a beginning, a middle, and an end.

According to Aristotle, the beginning should be self-contained, requiring no prior context to understand. It should establish the initial situation without prompting the reader to ask “why?” or “how?” The middle should logically develop from the beginning, escalating the story’s conflicts and introducing complications. Finally, the end should provide a satisfying resolution, ideally without hinting at further unresolved issues.

While Aristotle’s model provides a basic framework, many stories deviate from this simple triangle, incorporating greater complexity and nuance. Freytag’s Pyramid builds upon Aristotle’s foundation by offering a more detailed structural model.

Freytag’s Pyramid: A Five-Act Structure

Freytag’s Pyramid, developed by Gustav Freytag in the 19th century, expands on Aristotle’s three-part structure, offering a five-part dramatic arc that is widely applicable to storytelling.

- Exposition: This is the story’s opening, where the writer introduces the main characters, setting, initial atmosphere, and underlying themes. It sets the stage for the narrative to unfold and familiarizes the audience with the story’s world.

- Rising Action: The rising action begins after the inciting incident, the event that disrupts the initial equilibrium and sets the story’s central conflict in motion. This phase involves a series of cause-and-effect events that escalate tension, develop character relationships, and deepen the central conflict.

- Climax: The climax is the peak of the story’s tension and conflict. It’s the turning point where the protagonist confronts the central conflict directly. The outcome of the climax often determines the fate of the main characters and the resolution of the story’s core issues.

- Falling Action: Following the climax, the falling action depicts the immediate consequences and aftermath. Characters react to the climax, deal with its repercussions, and begin to process the changes it brings to their lives and futures.

- Denouement: The denouement, or resolution, is the story’s conclusion. It ties up loose ends, resolves remaining conflicts, and provides a sense of closure. Some denouements are open-ended, leaving the reader to ponder the story’s lasting implications.

For a more in-depth exploration of Freytag’s Pyramid, resources are readily available online.

Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc: A Modern Plot Blueprint

Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc further refines Freytag’s Pyramid, offering a more granular breakdown of plot development. Watts posits that a complete narrative arc progresses through eight distinct plot points:

- Stasis: The protagonist’s ordinary, everyday life is presented, establishing the initial status quo before any disruption occurs.

- Trigger: An event beyond the protagonist’s control, the “trigger,” disrupts the stasis and sets the story’s conflict in motion. This is akin to the inciting incident.

- The Quest: Comparable to the rising action, the quest is the protagonist’s journey to confront and resolve the central conflict initiated by the trigger.

- Surprise: Unexpected but plausible events or revelations complicate the protagonist’s quest. These surprises can manifest as obstacles, complications, internal flaws, or unforeseen circumstances.

- Critical Choice: The protagonist reaches a point where they must make a significant, life-altering decision. This choice reveals their true character and dramatically alters the course of the narrative.

- Climax: The direct consequence of the critical choice, the climax is the point of highest tension in the story. It determines the immediate outcome of the protagonist’s decision and the peak of the central conflict.

- Reversal: The reversal represents the protagonist’s reaction to the climax. It signifies a shift in their status—whether social standing, personal outlook, or even life itself. The protagonist is irrevocably changed by the climax.

- Resolution: The resolution marks the return to a new stasis. A new normal emerges from the ashes of the conflict and climax. Life continues, but fundamentally altered by the events of the story.

By structuring a plot through these eight points, Watts argues, writers can create a complete and satisfying narrative arc. Further details can be found in Watts’ book, Write a Novel and Get It Published.

Save the Cat: A Screenwriting-Inspired Structure

The “Save the Cat” plot structure, developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder, originated in screenwriting but offers a highly detailed and versatile framework applicable to various forms of storytelling. It emphasizes specific “beats” or plot points that occur at predictable intervals within a narrative.

Instead of reiterating the entire structure here, a comprehensive breakdown of “Save the Cat,” including a useful worksheet, is available at resources like Reedsy.

The Hero’s Journey: Archetypal Narrative Pattern

The Hero’s Journey, popularized by Joseph Campbell, identifies a recurring pattern in myths and stories across cultures. Campbell argued that stories often follow a three-act structure, representing the transformative journey a hero undertakes.

These three acts are:

- The Departure Act: The hero leaves their ordinary world, embarking on an adventure.

- The Initiation Act: The hero faces trials, encounters allies and enemies, and undergoes significant transformation in a new and unfamiliar world.

- The Return Act: The hero returns to their ordinary world, now changed by their experiences and often bringing a boon or elixir that benefits their community.

Christopher Vogler, in The Writer’s Journey, expanded this three-act structure into a detailed 12-step process, providing a more granular roadmap for the hero’s journey.

The Departure Act

- The Ordinary World: The hero is introduced in their mundane, everyday setting, allowing the audience to understand their starting point.

- Call to Adventure: The hero receives an invitation or challenge that disrupts their ordinary world and compels them to embark on a journey.

- Refusing the Call: Initially, the hero hesitates or refuses the call to adventure, often due to fear or reluctance to leave their comfort zone.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero encounters a mentor figure who provides guidance, encouragement, and often essential tools or knowledge needed for the journey.

The Initiation Act

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero commits to the adventure, leaving their ordinary world and entering a new, unfamiliar realm. This is a point of no return.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero faces various challenges, tests, and trials in the new world. They also encounter allies who aid them and enemies who oppose them, shaping the conflict and relationships within the narrative.

- Approach to the Inmost Cave: The “inmost cave” represents the heart of the hero’s challenge, the most dangerous and central location of their journey. The hero prepares to confront their greatest fear or obstacle.

- Ordeal: The hero faces a major crisis, often a life-or-death situation. This is a crucial turning point where they confront their deepest fears and undergo a significant transformation.

- Reward (Seizing the Sword): Having survived the ordeal, the hero gains a reward, which could be tangible (treasure, a weapon) or intangible (knowledge, self-realization).

The Return Act

- The Road Back: The hero begins the journey back to their ordinary world, but the return is not without its own challenges and dangers.

- Resurrection: The hero faces a final, climactic test, often mirroring the ordeal but on a higher level. This tests whether they have truly learned and transformed throughout their journey.

- Return with the Elixir: The hero returns to their ordinary world, transformed by their journey and bringing with them an “elixir” – a boon, treasure, or wisdom that benefits their community or world. They have become a changed person.

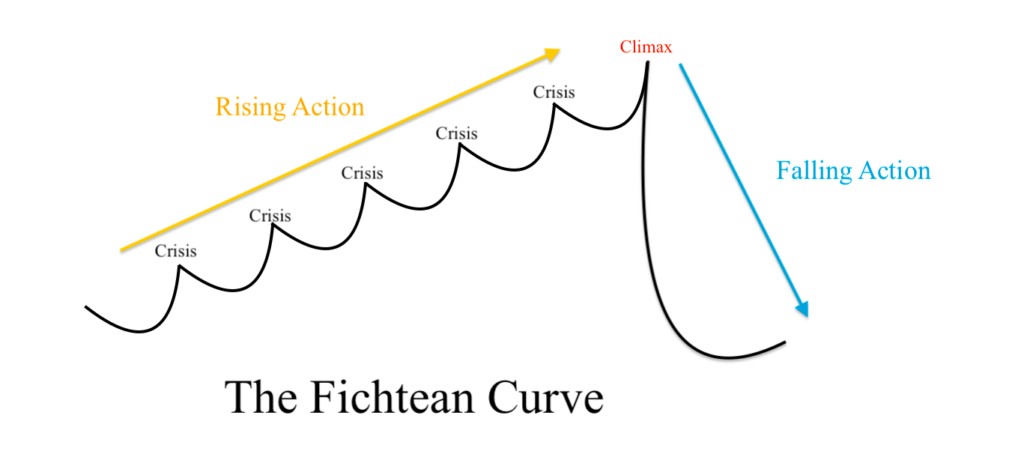

Fichtean Curve: Escalating Action and Climax

The Fichtean Curve, described by John Gardner in The Art of Fiction, is particularly suited to pulp fiction and mystery stories, but applicable to various genres. It emphasizes a plot structure driven by escalating conflict leading to a single climax, followed by a rapid resolution.

The Fichtean Curve consists of three main parts:

- Rising Action: This constitutes the majority of the story (roughly two-thirds). It’s characterized by a series of escalating conflicts and mini-climaxes that build tension and propel the narrative forward. The rising action is not a smooth upward slope but involves peaks and valleys of conflict, keeping the reader engaged.

- Climax: A single, decisive climax is the culmination of the rising action. It’s the point of highest tension and the resolution of the central conflict.

- Falling Action: Following the climax, the falling action is brief and swift. Loose ends are quickly tied up, and the story moves rapidly toward its conclusion.

Agatha Christie’s mystery novels, such as Murder on the Orient Express, exemplify the Fichtean Curve. Detective Hercule Poirot systematically investigates suspects, uncovering secrets and raising tensions through a series of mini-conflicts, all leading to the dramatic reveal of the murderer in the climax.

The Role of Conflict in Plot

Conflict is often considered the lifeblood of plot. But is it always essential? What is plot without conflict?

Conflict, in narrative terms, is the opposition or struggle that characters face. It’s not always overt arguments or physical battles. Conflict encompasses any force working against a character’s goals and desires. This can be:

- External Conflict: Conflict arising from outside forces, such as antagonists, societal structures, natural disasters, or specific situations.

- Internal Conflict: Conflict originating within a character, such as moral dilemmas, psychological struggles, conflicting desires, or personal flaws.

Conflict typically serves as the driving force of the plot. It’s the catalyst for the inciting incident, fuels the rising action, culminates in the climax, and is resolved (or not) in the denouement. Plot relies on conflict to maintain reader engagement and create narrative drive.

If you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict.

However, it’s important to note that the centrality of conflict in plot is a predominantly Western narrative tradition. Eastern storytelling traditions, such as Kishōtenketsu, may prioritize character development and reactions to external situations over conflict-driven plots. Kishōtenketsu emphasizes character complexities and dilemmas within a world they cannot fully control, where conflict may be present but not the primary engine of the narrative.

For a deeper understanding of conflict in storytelling, explore resources that delve into the nuances of narrative conflict.

Essential Plot Devices

Plot devices are techniques writers employ to shape the narrative, maintain reader interest, and add layers of meaning to their stories. While plot structures provide the overall framework, plot devices are the tools used to manipulate and enhance the story’s progression.

Aristotle’s Core Plot Devices

In Poetics, Aristotle identified three key plot devices fundamental to many stories:

1. Anagnorisis (Recognition)

“Luke, I am your father!” Anagnorisis is the moment of critical realization or discovery where the protagonist transitions from ignorance to knowledge. Often preceding the climax, anagnorisis is the crucial piece of information that empowers the protagonist to resolve the central conflict. It’s a moment of revelation that shifts the character’s understanding and drives the plot forward.

2. Pathos (Suffering)

Aristotle defines pathos as “a destructive or painful action.” This encompasses physical suffering, such as death or injury, but also emotional and existential pain. Aristotle argued that stories often confront extreme suffering, and this element is crucial for plot propulsion and emotional impact. (This is distinct from the rhetorical device of “pathos,” which aims to evoke audience emotions.)

3. Peripeteia (Reversal)

Peripeteia is a sudden reversal of fortune, where circumstances shift from good to bad or vice versa. Often occurring in conjunction with anagnorisis, peripeteia is frequently the outcome of the climax. The climax determines whether the protagonist’s story arc will ultimately lead to a positive or tragic resolution.

Devices for Structuring Plot

These devices contribute to the overall shape and flow of the plot:

Backstory

Backstory refers to events that occurred before the main narrative begins. It provides context, character motivation, and historical parallels that enrich the present story. While backstory events precede the exposition, they are often revealed strategically throughout the narrative, sometimes through flashbacks.

Deus Ex Machina

Deus ex machina (Latin for “god from the machine”) is a plot device where a seemingly insurmountable problem is suddenly resolved by an unexpected and improbable intervention, often from an outside force or coincidence. While it can provide a quick resolution, deus ex machina is often criticized as a weak or contrived plot device, especially in serious narratives, as it can undermine character agency and thematic depth. However, it can be used effectively in comedy or absurdist works.

In Media Res

In media res (Latin for “in the midst of things”) is a narrative technique where the story begins in the middle of the action, rather than with traditional exposition. The reader is immediately thrown into a scene of conflict or intrigue, lacking initial context. This technique can create immediate reader engagement and suspense. The story then gradually reveals necessary background information through flashbacks or exposition as the narrative progresses.

Plot Voucher

A plot voucher is an element introduced early in the story that seems insignificant at the time but becomes crucial later in the plot. It’s often an object, piece of information, or a seemingly chance encounter that pays off unexpectedly. The protagonist (and often the reader) may not initially realize the voucher’s importance. In the Harry Potter series, the Golden Snitch containing the Resurrection Stone serves as a plot voucher, its significance revealed much later in the narrative.

Devices for Plot Complication and Intrigue

These devices enhance suspense, create twists, and keep readers guessing:

Cliffhanger

A cliffhanger is a narrative device where a chapter, episode, or story ends abruptly at a moment of high tension or suspense, typically just before a crucial event or revelation. The resolution is withheld, leaving the audience in suspense and eager to know what happens next. Cliffhangers are common in serialized narratives but can also be used for literary effect, as in One Thousand and One Nights, where Scheherazade uses cliffhangers to postpone her execution.

MacGuffin

A MacGuffin is a plot device defined by its lack of intrinsic value. It’s an object, person, or goal that the protagonist is highly motivated to pursue, and this pursuit drives the plot forward. However, the MacGuffin itself is ultimately unimportant or even meaningless. Its primary function is to motivate characters and generate conflict. The falcon statuette in The Maltese Falcon is a classic example – its actual value is irrelevant; it’s the chase for it that propels the narrative.

Red Herring

A red herring is a misleading clue or piece of information designed to distract the reader (or characters within the story) from the actual truth or solution. It creates false trails and misdirection, often used in mystery and suspense genres to heighten intrigue and create surprise reveals. While effective in creating twists, overuse of red herrings can frustrate readers or undermine their trust in the narrative. (This is distinct from the logical fallacy “red herring,” which is an irrelevant distraction in argumentation.)

For a wider array of plot devices and storytelling techniques, resources on the art of storytelling offer further exploration.

8 Common Types of Plot in Literature

Certain plot patterns recur throughout literature, particularly within genre fiction. These plot types build upon the devices discussed and often utilize specific tropes and archetypes to deliver familiar yet engaging narrative experiences.

Some of the following plot types were initially categorized by Christopher Booker in The Seven Basic Plots. (Less frequently encountered plots have been omitted for brevity).

The plot of a story can often be categorized into these common types:

1. Quest Plot

The quest plot, often mirroring the Hero’s Journey, centers on a protagonist who embarks on a journey from their home in search of something specific. This could be a physical object (treasure), a person (love), knowledge (truth), a new location (home), or a solution to a problem. The protagonist often gathers allies and faces obstacles during their journey. The quest plot typically results in the protagonist’s transformation—they return (if they survive) wiser, stronger, and fundamentally changed by their experiences.

Examples: The Lord of the Rings, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, The Harry Potter Series.

2. Tragedy Plot

A tragedy plot focuses on a protagonist who, despite good intentions and often noble qualities, ultimately fails to achieve their goals or resolve the central conflict. This failure is often attributed to their own flaws (hamartia or tragic flaw), external circumstances, or impossible moral dilemmas. Tragedies evoke empathy for the protagonist, even in their downfall. The protagonist’s demise, often resulting in death or significant loss, serves as a powerful exploration of human limitations and fate.

Examples: Romeo & Juliet, The Great Gatsby, Oedipus Rex, Frankenstein, Of Mice and Men, Wuthering Heights.

3. Rags to Riches Plot

The rags to riches plot traces the protagonist’s journey from poverty and hardship to wealth and success. These narratives often explore themes of social class, identity, and the impact of sudden wealth on an individual’s character and relationships. The plot focuses on the protagonist’s adaptation to their new circumstances, the challenges of wealth, and what they ultimately value in life.

Examples: Great Expectations, The Count of Monte Cristo, Q & A (adapted as Slumdog Millionaire).

4. Story Within a Story Plot (Embedded Narrative)

The story within a story, or embedded narrative, is a less structured plot type where a secondary story is woven into the main narrative. This embedded story, with its own conflict and resolution, serves to enhance or comment on the main plot. Embedded narratives can reflect or contrast the themes of the primary story, adding layers of meaning and complexity. It differs from parallel plot in that the embedded story serves to support the main narrative, not exist as an equally weighted storyline.

Examples: The Brothers Karamazov, Hamlet, Moby-Dick, Afterworlds, Don Quixote.

5. Parallel Plot

A parallel plot involves two or more distinct storylines that unfold concurrently within the narrative. These storylines are often interconnected thematically or through character relationships, and they influence each other throughout the story. Each plotline in a parallel plot is considered equally important to the overall narrative structure and meaning.

Examples: Kafka on the Shore, A Tale of Two Cities, Break the Bodies, Haunt the Bones, The Testaments, In the Time of the Butterflies.

6. Rebellion Against “The One” Plot

The rebellion plot centers on a protagonist who actively resists a powerful, oppressive, and often totalitarian antagonist or system (“The One”). Despite their efforts, the protagonist is often outmatched and ill-equipped to defeat such a force single-handedly. These stories frequently end with the protagonist’s failure, submission, or even death, highlighting the overwhelming power of oppressive forces and the challenges of individual resistance.

Examples: 1984, The Hunger Games Series, “Harrison Bergeron”, The Handmaid’s Tale.

7. Anticlimax Plot

The anticlimax plot deviates from traditional structures by focusing on the falling action after a climax that has already occurred (often off-page or in the backstory). The narrative explores the aftermath and consequences of a major event, rather than building towards a central climax within the story’s present timeline. The climax is implied or referred to, but the story’s focus is on the denouement and the characters’ lives in the wake of significant events. This is different from the plot device “anticlimax,” which refers to a disappointing or underwhelming resolution.

Examples: The Sound and the Fury, Encircling, Oryx & Crake.

8. Voyage and Return Plot

Voyage and return plots involve protagonists who journey to a new and unfamiliar world or setting and then return to their original world, transformed by their experiences. While quest plots can also be voyage and return stories, not all voyage and return plots are quests. The protagonist’s journey to and from the new world, and the act of navigating and overcoming challenges in both worlds, are central to this plot type. The return journey emphasizes the protagonist’s transformation and the impact of their experiences on their original world.

Examples: The Odyssey, Coraline, The Lord of the Flies, Gulliver’s Travels, Candide, The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.

Plot-Driven vs. Character-Driven Stories

A common distinction in fiction is whether a story is “plot-driven” or “character-driven.” This distinction highlights the primary force shaping the narrative:

- Plot-Driven Stories: In plot-driven stories, the plot itself takes precedence. Events and actions unfold primarily to advance the plot, and characters often serve to facilitate these plot developments. Genre fiction, such as thrillers, mysteries, and action stories, often leans towards plot-driven narratives.

- Character-Driven Stories: In character-driven stories, the characters and their internal journeys are central. The plot unfolds as a consequence of characters’ personalities, motivations, decisions, and relationships. Literary fiction often prioritizes character development and psychological realism, making it character-driven.

This distinction, while useful for categorization, is not absolute. Many stories blend elements of both plot and character focus. Literary fiction can incorporate intricate plots, and genre fiction can feature deeply developed characters. Effective storytelling often involves a dynamic relationship between plot and character, where each element informs and enriches the other.

Your story should build a working relationship between the characters and the plot, as both are essential elements of the storyteller’s toolkit.

Plot vs. Story: Clarifying the Terms

While “plot” and “story” are often used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings in narrative theory.

Plot Definition: Plot refers to the sequence of events in a narrative, emphasizing the cause-and-effect relationships between those events. Think of plot as the structural framework or skeleton of the story—the what, when, and where of the narrative. What happens, in what order, and in what setting?

Story Definition: Story is the broader concept encompassing the entirety of the narrative work. It includes the plot, but also the characters, themes, setting, style, and overall message. Story answers the who, why, and how of the narrative. Who are the characters, why are these events unfolding, and how do characters respond and resolve the conflict?

In essence, plot is a component within the larger entity of story. A compelling plot is essential for a strong story, but story encompasses a wider range of elements that contribute to the overall narrative experience.

Explore Plot Further at Writers.com

Writers approach plot creation in diverse ways. “Plotters” meticulously plan their plots in advance, outlining every event before writing. “Pantsers,” on the other hand, write more organically, developing the plot as they go, “by the seat of their pants.”

Regardless of your writing style, Writers.com offers resources to enhance your understanding and application of plot. Explore courses on plotting your novel or engage in various writing classes to refine your storytelling skills.