Hurricanes, typhoons, and tropical cyclones – these are all names for the same powerful weather phenomenon: a tropical cyclone. But what is called a hurricane in one part of the world is known by a different name in another. The term “tropical cyclone” itself is the broad, scientific term used by meteorologists to describe these rotating storm systems.

So, what is called a tropical cyclone? In essence, it is a system of clouds and thunderstorms that rotates and is organized. These storms develop over warm tropical or subtropical waters and are characterized by a closed, low-level circulation – meaning the air at the surface spirals in towards the center.

The intensity of these storms also dictates what is called them. The weakest form of a tropical cyclone is what is called a tropical depression. When a tropical depression gains strength and its maximum sustained winds reach 39 miles per hour (mph), it graduates to what is called a tropical storm. It’s at this stage that the storm receives a name.

The classification changes again when a tropical cyclone’s maximum sustained winds reach 74 mph or higher. Now, what is called the storm depends on its location:

- In the North Atlantic, the central North Pacific, and the eastern North Pacific, a tropical cyclone with winds of 74 mph or more is called a hurricane.

- In the Northwest Pacific, the same type of storm is called a typhoon.

- Meanwhile, in the South Pacific and the Indian Ocean, the generic term tropical cyclone is called upon, regardless of the storm’s wind strength once it reaches the 74 mph threshold.

Several key ingredients must come together for these powerful storms to form. These include:

- A pre-existing weather disturbance: This could be a cluster of thunderstorms.

- Warm tropical oceans: Warm water provides the necessary energy for the storm to develop.

- Moisture: Abundant moisture in the lower and mid-levels of the atmosphere fuels the storm.

- Relatively light winds: Consistent winds throughout the storm’s vertical structure allow it to organize and intensify.

When these conditions align and persist, they can lead to the development of the intense winds, massive waves, heavy rainfall, and flooding associated with hurricanes, typhoons, and tropical cyclones.

Sometimes, even if a weather system doesn’t fully meet all the criteria to be classified as a tropical cyclone, it can still pose a threat. If such a system is predicted to bring tropical storm or hurricane-force winds to land within 48 hours, in the Atlantic basin and the central and eastern North Pacific basins, it is called a potential tropical cyclone. This designation is used to trigger early warnings and preparations.

In the Atlantic, the official hurricane season spans from June 1st to November 30th. During this period, a significant 97% of tropical cyclone activity occurs. However, it’s important to remember that hurricanes can and do happen outside of these dates.

To further understand these storms, it’s helpful to know the main parts of a tropical cyclone. These are:

- Rainbands: Outer spiral bands of clouds and thunderstorms that rotate around the storm’s center.

- The Eye: The relatively calm and clear center of the storm where air sinks.

- The Eyewall: A ring of intense thunderstorms surrounding the eye, containing the storm’s strongest winds and heaviest rainfall.

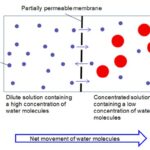

Air within a tropical cyclone spirals inwards towards the center in a counter-clockwise direction in the Northern Hemisphere (and clockwise in the Southern Hemisphere) and then rises and flows outwards at the top in the opposite direction.

Understanding what is called these different weather systems and their characteristics is crucial for coastal communities to prepare for and respond to these powerful forces of nature. The National Ocean Service and other agencies provide vital information and resources to help communities build resilience against major coastal storms like hurricanes and typhoons.

Last updated: 06/16/24 Author: NOAA