Iron deficiency is a widespread health issue, affecting billions globally. While iron deficiency anemia (IDA) is commonly recognized, iron deficiency without anemia (IDWA) is often overlooked, despite being even more prevalent. Ferritin, a protein that stores iron, is a key indicator of your body’s iron levels. But What Is Dangerously Low Ferritin Levels, and why should you be concerned?

This article delves into the critical issue of dangerously low ferritin levels, a condition that can signal significant health risks even before anemia develops. We’ll explore the definition of low ferritin, why it matters, the potential causes, and the implications for your overall well-being. Understanding dangerously low ferritin is crucial for proactive health management and ensuring you receive timely and effective treatment.

Understanding Iron Deficiency and Ferritin’s Role

Iron is essential for numerous bodily functions, most notably in carrying oxygen throughout your body as a component of hemoglobin in red blood cells. However, iron also plays a vital role in energy production, cell growth, and various enzyme reactions. Ferritin acts as the primary iron storage protein in your body, reflecting your iron reserves. Measuring ferritin levels is a direct way to assess how much iron your body has stored.

Low ferritin levels indicate depleted iron stores, a condition known as iron deficiency (ID). It’s important to distinguish between iron deficiency and iron deficiency anemia. Anemia is a more severe stage where iron deficiency has become so pronounced that it leads to a decrease in hemoglobin levels, resulting in a reduced capacity to carry oxygen. IDWA, on the other hand, occurs when iron stores are low (indicated by low ferritin), but hemoglobin levels are still within the normal range. This “pre-anemic” state is often missed, yet it can still significantly impact your health.

Diagnostic Ferritin Levels: What’s Considered Low?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines low ferritin as levels below 15 μg/L for adults. However, in clinical practice, many healthcare professionals consider ferritin levels below 30 μg/L as indicative of iron deficiency. This is because even levels between 15-30 μg/L, while not “dangerously low” in the most immediate sense, still represent depleted iron stores and can lead to symptoms and health issues over time.

In situations involving chronic inflammation, such as chronic diseases, infections, or autoimmune conditions, ferritin levels can be misleadingly elevated as ferritin is also an acute-phase reactant. In these cases, the cut-off for diagnosing iron deficiency is often raised to 100 μg/L. If ferritin is between 100-300 μg/L in inflammatory conditions, another test, transferrin saturation (TSAT), is crucial to accurately assess iron status. TSAT levels below 20% alongside elevated ferritin in inflammation suggest iron deficiency. Serum iron levels alone are not reliable for diagnosis due to their fluctuations throughout the day.

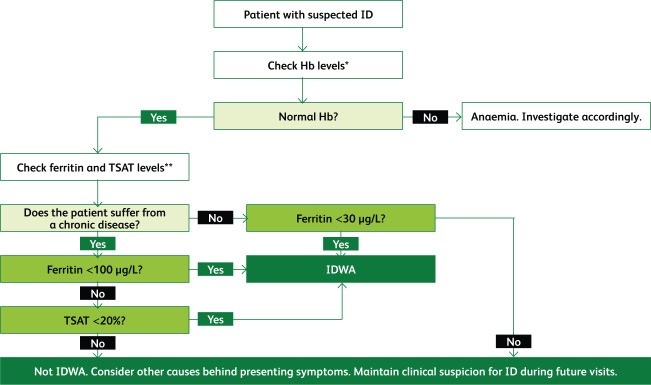

Figure 1: Diagnostic Algorithm for Iron Deficiency

Algorithm for Diagnosing Iron Deficiency: Ferritin and Transferrin Saturation (TSAT) Testing. This algorithm illustrates the interpretation of diagnostic tests for iron deficiency, not necessarily the order in which they are requested.

While other tests like hepcidin, soluble transferrin receptor (sTFR), and reticulocyte hemoglobin content (RHC) can be helpful, ferritin and TSAT remain the most commonly used and readily available diagnostic tools. It’s essential to remember that normal hemoglobin ranges are population-based averages. An individual might have a “normal” hemoglobin level but still experience symptoms of iron deficiency if their personal optimal level is higher. Therefore, clinicians should assess patients individually, considering their symptoms and overall health, rather than relying solely on strict hemoglobin cut-offs.

What Causes Dangerously Low Ferritin Levels?

Iron deficiency arises when iron intake, absorption, or utilization is insufficient to meet the body’s needs, or when iron losses exceed intake. These imbalances can stem from various factors, categorized broadly as:

-

Inadequate Dietary Intake: Consuming insufficient iron-rich foods, particularly heme iron found in animal products, can lead to deficiency. Vegan and vegetarian diets, while healthy, require careful planning to ensure adequate iron intake. Increased iron requirements, such as during growth spurts in children and adolescence, and pregnancy, also increase the risk of deficiency if dietary intake isn’t adjusted accordingly.

-

Increased Iron Needs: Periods of rapid growth, pregnancy, and intense athletic training significantly increase iron requirements. Athletes, especially endurance athletes, are at higher risk due to increased iron losses through sweat, urine, and potentially gastrointestinal bleeding, as well as inflammation-induced iron restriction.

-

Reduced Iron Absorption: Iron absorption primarily occurs in the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). Conditions that affect the stomach or small intestine can impair iron absorption. Reduced stomach acid (achlorhydria), often caused by autoimmune gastritis or prolonged use of proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 receptor antagonists, hinders the conversion of dietary iron to a more absorbable form. Bariatric surgery, Helicobacter pylori infection, celiac disease, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) can also reduce absorptive surface area or disrupt iron absorption mechanisms. Certain dietary components, such as coffee, tea, and calcium, consumed in close proximity to iron-rich meals can also inhibit iron absorption.

-

Chronic Inflammation: Chronic inflammatory conditions, including infections, autoimmune diseases, chronic kidney disease, heart failure, and certain cancers, can lead to functional iron deficiency (FID). In FID, inflammation triggers the release of hepcidin, a hormone that restricts iron availability. Hepcidin blocks ferroportin, the protein responsible for iron transport out of cells, leading to iron being trapped within storage cells and limiting its availability for red blood cell production and other vital functions.

-

Chronic Blood Loss: Significant or ongoing blood loss is a major cause of iron deficiency. In women, heavy menstrual bleeding (menorrhagia) is a common culprit. Gastrointestinal bleeding, which can be occult (hidden) and caused by conditions like ulcers, angiodysplasia, or gastrointestinal cancers, is another significant cause. Frequent blood donation, nosebleeds, surgical procedures, trauma, and the use of anticoagulants or antiplatelet medications can also contribute to iron loss.

Figure 2: Causes of Iron Deficiency

Common Causes of Iron Deficiency: Dietary Intake, Absorption Issues, Inflammation, and Blood Loss. This figure summarizes the diverse causes of iron deficiency, ranging from dietary factors to underlying medical conditions.

Identifying the underlying cause of iron deficiency is crucial for effective treatment. It’s not just about raising ferritin levels but addressing the root issue to prevent recurrence.

Health Risks and Symptoms of Dangerously Low Ferritin

While severe iron deficiency leads to anemia with well-known symptoms like fatigue and paleness, even IDWA and dangerously low ferritin levels can cause a range of symptoms and health problems. Iron is not just about hemoglobin; it’s vital for mitochondrial function, cellular respiration, and various enzymatic processes. Cells with high metabolic demands, such as heart and muscle cells, are particularly vulnerable to iron deficiency.

Symptoms of iron deficiency, whether with or without anemia, are often nonspecific, making diagnosis challenging. Common symptoms include:

-

Fatigue and Weakness: This is the most common symptom, often described as persistent tiredness, lack of energy, and feeling easily exhausted.

-

Exercise Intolerance: Reduced stamina, shortness of breath during exertion, and difficulty performing physical activities.

-

Pale Skin: Though less pronounced in IDWA, paleness, especially in the conjunctiva (inner eyelid) and nail beds, can be noticeable in more severe cases.

-

Headaches and Dizziness: Iron deficiency can affect blood flow to the brain, leading to headaches, lightheadedness, and dizziness.

-

Restless Legs Syndrome (RLS): An irresistible urge to move the legs, often accompanied by uncomfortable sensations, particularly in the evening or at night.

-

Hair Loss and Brittle Nails: Iron is important for hair growth and nail health. Deficiency can contribute to hair thinning, hair loss, and brittle, spoon-shaped nails (koilonychia).

-

Pica: Unusual cravings for non-food substances like ice, clay, or dirt.

-

Cognitive Impairment: Difficulty concentrating, memory problems, and reduced cognitive function can occur even in IDWA.

-

Heart Palpitations and Chest Pain: In more severe cases, iron deficiency can strain the heart, leading to palpitations, rapid heartbeat, and chest discomfort.

In individuals with pre-existing conditions like heart failure or inflammatory bowel disease, iron deficiency can worsen their prognosis and quality of life. For example, in heart failure patients, iron deficiency impairs mitochondrial function, exacerbates muscle weakness, and increases mortality risk.

Figure 3: Effects of Iron Deficiency on the Body

Health Effects of Iron Deficiency: Fatigue, Cardiac Issues, and Impaired Metabolism. This image visually summarizes the wide-ranging impact of iron deficiency on various bodily systems and functions.

It’s crucial to recognize that these symptoms can significantly impact daily life, even in the absence of anemia. Ignoring low ferritin levels and associated symptoms can lead to a progressive decline in health and well-being.

Iron Deficiency and Pregnancy: A Critical Concern

Iron deficiency during pregnancy is particularly concerning due to its impact on both maternal and fetal health. Pregnant women have significantly increased iron requirements to support the growing fetus and placenta, as well as increased maternal blood volume.

Iron deficiency anemia in pregnancy is linked to increased maternal morbidity, including fatigue, increased risk of infection, and postpartum depression. More critically, it increases the risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes such as:

- Intrauterine Growth Restriction (IUGR): The fetus not growing at the expected rate.

- Prematurity: Birth before 37 weeks of gestation.

- Low Birth Weight: Babies born weighing less than 5.5 pounds.

Even iron deficiency without anemia at the beginning of pregnancy increases the likelihood of developing IDA later in pregnancy and delivering a baby with lower iron stores and birth weight. Crucially, during fetal development, iron is preferentially directed to red blood cell production. This means that iron deficiency can affect other organs, particularly the developing brain, even if hemoglobin levels remain within the normal range.

Iron deficiency during pregnancy and infancy has been linked to long-term neurocognitive deficits in children, including impaired memory, slower neural processing, and behavioral problems. These effects can persist even with postnatal iron supplementation and may be measurable into adolescence and adulthood.

Therefore, screening for and treating iron deficiency before conception and throughout pregnancy is vital. Iron supplementation during pregnancy, often with oral iron, is routinely recommended. In cases of persistent deficiency or intolerance to oral iron, intravenous (IV) iron may be necessary, particularly in the second and third trimesters. Newborns of iron-deficient mothers should also be screened and treated for iron deficiency to mitigate the risk of long-term neurodevelopmental consequences.

Preoperative Iron Deficiency: Risks in Surgery

The impact of preoperative iron deficiency without anemia on surgical outcomes is increasingly recognized as a significant concern in patient blood management. Patient blood management strategies aim to optimize a patient’s own blood volume and red blood cell mass before, during, and after surgery to minimize the need for blood transfusions and improve outcomes.

Preoperative IDWA increases the risk of:

- Postoperative Infection: Iron is crucial for immune function, and deficiency can impair the body’s ability to fight infection after surgery.

- Postoperative Fatigue: Surgery itself can be tiring, and pre-existing iron deficiency can exacerbate fatigue during recovery.

- Blood Transfusion: Patients with preoperative IDWA are more likely to require blood transfusions during or after surgery due to reduced red blood cell production and increased blood loss.

- Postoperative Anemia: Even if not anemic before surgery, patients with IDWA are at higher risk of developing postoperative anemia.

Studies have shown that preoperative iron supplementation, including IV iron in some cases, can reduce the need for blood transfusions and improve recovery in patients undergoing various surgeries, including cardiac and orthopedic procedures.

Guidelines recommend screening for and treating iron deficiency, including IDWA, in patients scheduled for elective surgeries with significant anticipated blood loss. Ideally, iron deficiency should be corrected before surgery. If surgery is more than 6 weeks away, oral iron supplementation is typically recommended. For shorter timeframes, IV iron may be preferred for faster iron repletion.

Collaboration between primary care physicians and specialists is crucial to ensure timely screening and management of preoperative iron deficiency. Addressing iron deficiency before surgery not only improves patient outcomes but can also reduce healthcare costs associated with transfusions and complications.

Managing Dangerously Low Ferritin Levels: Treatment Strategies

Treating iron deficiency, including IDWA, is essential to alleviate symptoms, improve overall health, and prevent complications. The primary goal of treatment is to replenish iron stores and raise ferritin levels to a target of at least 100 μg/L, while also addressing the underlying cause of the deficiency.

Dietary Modifications:

Dietary advice is a cornerstone of managing iron deficiency. Patients should be encouraged to consume iron-rich foods regularly. Heme iron, found in animal products like red meat, poultry, and fish, is more readily absorbed than non-heme iron from plant-based sources. Combining iron-rich foods with vitamin C-rich foods (citrus fruits, berries, peppers) enhances non-heme iron absorption. Conversely, foods and drinks that inhibit iron absorption, such as tea, coffee, calcium-rich dairy products, and high-fiber grains, should be consumed separately from iron-rich meals. In some cases, referral to a registered dietitian can provide personalized dietary guidance. However, dietary changes alone are often insufficient to correct established iron deficiency, necessitating iron supplementation.

Oral Iron Supplementation:

Oral iron supplements are the first-line treatment for most cases of iron deficiency. Ferrous sulfate, ferrous fumarate, and ferrous gluconate are common forms of oral iron. The recommended daily dose typically ranges from 28-50 mg of elemental iron, or 100 mg every other day, for adults. Taking iron supplements on alternate days, rather than daily, may improve absorption and reduce side effects by better regulating hepcidin levels.

Gastrointestinal side effects, such as constipation, diarrhea, nausea, and stomach upset, are common with oral iron and can lead to poor adherence. Strategies to minimize side effects include:

- Starting with a lower dose and gradually increasing it.

- Taking iron with food (although this may slightly reduce absorption).

- Using slow-release formulations (although their absorption may be less efficient).

- Managing constipation with increased fiber and fluids.

Patients should be advised to take oral iron for several months to replenish iron stores fully. Response to treatment is typically assessed by monitoring hemoglobin, ferritin, and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, along with red blood cell indices, 6-8 weeks after starting supplementation.

Intravenous (IV) Iron Supplementation:

IV iron is indicated when oral iron is ineffective, poorly tolerated, or insufficient to meet iron needs rapidly. Situations where IV iron is preferred include:

- Severe Iron Deficiency: When rapid iron repletion is necessary.

- Intolerance to Oral Iron: Due to significant gastrointestinal side effects.

- Malabsorption: In conditions like celiac disease, IBD, or after bariatric surgery.

- Chronic Inflammatory Conditions: Such as heart failure or chronic kidney disease, where hepcidin-mediated iron restriction limits the effectiveness of oral iron.

- Preoperative Iron Repletion: When surgery is scheduled within a few weeks and rapid iron correction is needed.

Modern IV iron formulations, such as iron sucrose, ferric carboxymaltose, and iron isomaltoside, are significantly safer than older high molecular weight iron dextran formulations. Severe allergic reactions are rare (around 1 in 250,000 administrations). Minor infusion reactions can occur in about 1% of patients and are usually manageable by slowing or temporarily stopping the infusion. IV iron should be administered in a setting where potential adverse reactions can be promptly managed.

Figure 4: Management Flowchart for Iron Deficiency Without Anemia (IDWA)

Iron Deficiency Without Anemia (IDWA) Management Flowchart: Diet, Oral and IV Iron Supplementation. This flowchart provides a visual guide to the stepwise approach in managing iron deficiency without anemia, starting with dietary advice and progressing to oral and intravenous iron options.

Follow-up and Monitoring:

Regardless of the treatment method, regular follow-up and monitoring are crucial. Ferritin levels should be checked every 6-12 months after treatment completion, especially in women with heavy menstrual bleeding or those planning pregnancy. Relapse of iron deficiency is possible, and ongoing monitoring helps ensure timely re-treatment if needed.

Conclusion: Recognizing and Addressing Dangerously Low Ferritin

Iron deficiency without anemia, indicated by dangerously low ferritin levels, is a widespread yet often underdiagnosed condition with significant health implications. It’s crucial to move beyond the misconception that iron deficiency only matters when anemia is present. Recognizing IDWA as a distinct clinical entity and understanding the importance of ferritin as an indicator of iron stores are the first steps towards better patient care.

Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for iron deficiency, particularly in at-risk populations such as women with heavy menstrual bleeding, pregnant women, athletes, individuals with chronic inflammatory conditions, and those with unexplained fatigue or other suggestive symptoms. Routine screening of ferritin levels, especially in these groups, can facilitate early diagnosis and intervention.

Further research is needed to refine diagnostic markers, optimize treatment strategies, and establish clear guidelines for managing IDWA. However, with current knowledge, a proactive approach to identifying and treating dangerously low ferritin levels, using dietary modifications, oral iron, and IV iron when appropriate, can significantly improve patient well-being and prevent the progression to more severe health consequences. Raising awareness among both healthcare professionals and the public about the importance of iron status and ferritin levels is essential for improving the management of this prevalent nutritional deficiency.

Key Points to Remember about Dangerously Low Ferritin Levels:

- Iron deficiency affects many bodily functions beyond hemoglobin production.

- Iron deficiency without anemia (IDWA) is a real and significant clinical condition, often indicated by low ferritin levels even with normal hemoglobin.

- Ferritin levels below 30 μg/L generally indicate iron deficiency, and levels below 15 μg/L are considered very low by WHO standards.

- Many factors can cause low ferritin, including inadequate diet, increased needs, poor absorption, chronic inflammation, and blood loss.

- Symptoms of low ferritin can be non-specific but can significantly impact quality of life, even without anemia.

- Iron deficiency in pregnancy has serious implications for both mother and child.

- Preoperative iron deficiency increases surgical risks.

- Treatment for low ferritin includes dietary changes, oral iron supplements, and IV iron in specific cases.

- Regular monitoring of ferritin levels is important to ensure effective management and prevent recurrence.

References