Electronegativity is a fundamental concept in chemistry, acting as a crucial compass for understanding how atoms interact and form molecules. Imagine atoms in a chemical bond as being engaged in a tug-of-war for electrons. Electronegativity is the measure of how strongly an atom attracts these shared electrons towards itself within a chemical bond. It’s not an intrinsic property of an isolated atom, but rather a description of its behavior when bonded to another atom.

To put it simply, electronegativity helps us predict the nature of chemical bonds and the overall behavior of molecules. Just like some individuals are naturally stronger in a tug-of-war, some elements are inherently more electronegative than others.

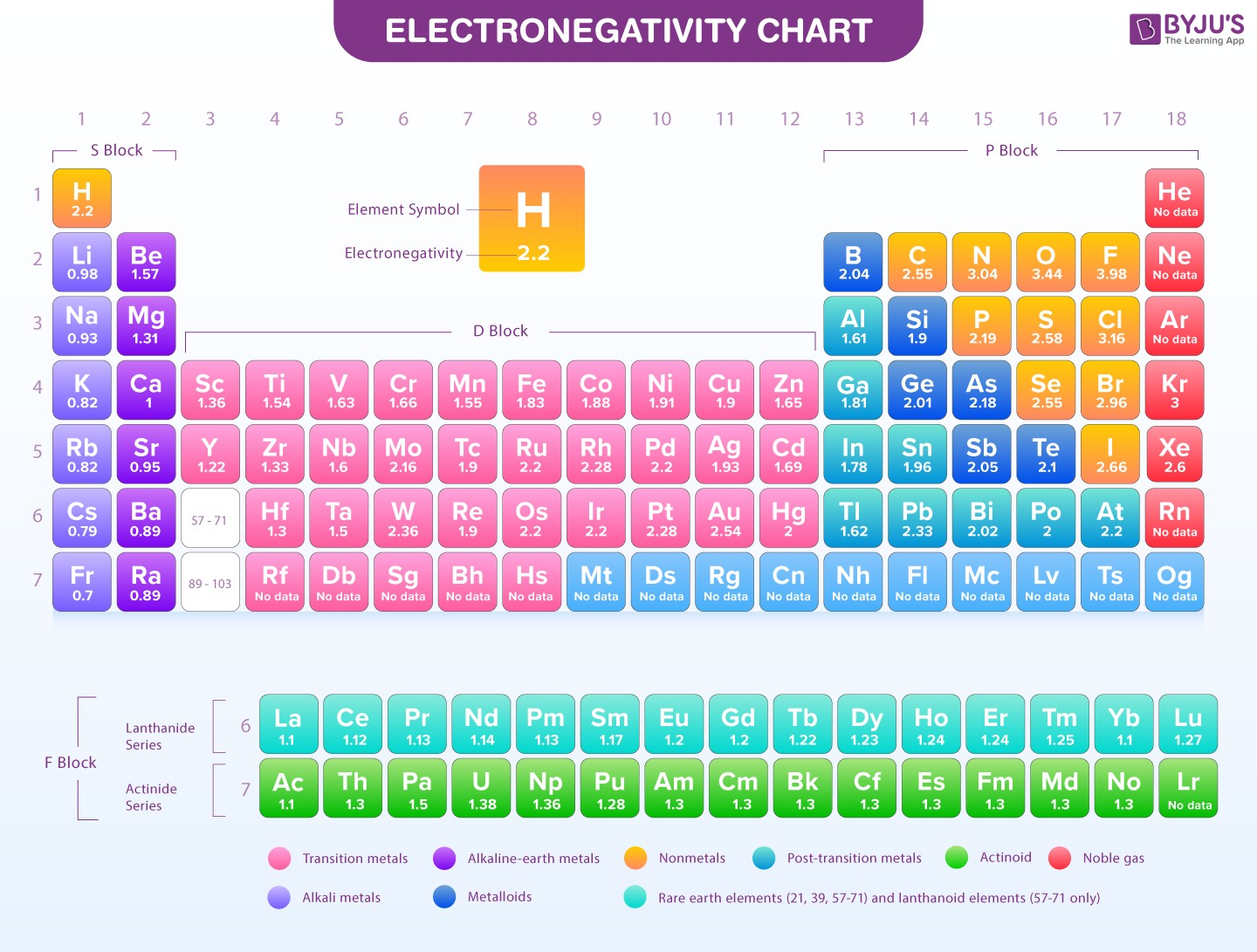

Fluorine consistently tops the chart as the most electronegative element, boasting a Pauling electronegativity value of 3.98 (often rounded to 4.0). On the opposite end of the spectrum, Cesium is considered the least electronegative element, with a value of 0.79. In fact, the concept of electropositivity is essentially the inverse of electronegativity. Therefore, Cesium, being the least electronegative, is considered the most electropositive.

The position of an element on the periodic table is a strong indicator of its electronegativity. Elements located towards the top right of the periodic table tend to be highly electronegative. This is largely because they are just a few electrons shy of achieving a full outer electron shell (valence shell), and their inner electron shells do little to shield the positive charge of the nucleus from the valence electrons. Conversely, elements on the bottom left of the periodic table, like Cesium and Francium (with electronegativity values around 0.7), are the least electronegative. Metals, in general, typically exhibit electronegativity values below 2.0.

In essence, Fluorine is the champion of electronegativity, while Cesium is at the opposite end, least eager to attract electrons in a bond.

The Profound Impact of Electronegativity on Covalent Bonds

Electronegativity plays a pivotal role in shaping the characteristics of covalent bonds, particularly their strength and polarity. The strength of a covalent bond is significantly influenced by the electronegativity difference between the atoms involved.

Consider homonuclear diatomic molecules, like H₂, Cl₂, and O₂. These molecules are composed of two identical atoms. Since both atoms have the same electronegativity, the shared pair of electrons in the covalent bond is distributed almost equally, residing roughly equidistant from both nuclei. These bonds are considered relatively “pure” covalent bonds, meaning they exhibit minimal polarity.

However, when covalent bonds form between atoms of different elements, things change dramatically. If there’s a difference in electronegativity between the bonded atoms, the bond becomes polarized. The more electronegative atom exerts a stronger pull on the shared electrons, drawing them closer to its nucleus. This unequal sharing results in the more electronegative atom acquiring a partial negative charge (denoted as δ-), and the less electronegative atom developing a partial positive charge (δ+). These partial charges are the hallmark of a polar covalent bond.

When Electronegativity Difference Leads to Ionic Bonds

In situations where there’s a substantial electronegativity difference between bonded atoms, the electron “tug-of-war” becomes so lopsided that the more electronegative atom can effectively wrest complete control of the bonding electrons from the less electronegative atom. This complete transfer of electrons leads to the formation of ions. The electronegative atom becomes an anion (negatively charged ion), having gained electrons, and the electropositive atom becomes a cation (positively charged ion), having lost electrons. This is the essence of ionic bonding.

It’s important to recognize that the distinction between covalent and ionic bonds isn’t always black and white. In reality, most bonds exist on a spectrum. Even bonds considered covalent can possess some degree of ionic character, and conversely, ionic bonds can exhibit a degree of covalent character. The extent of ionic character in a bond is directly related to the electronegativity difference between the bonding atoms. A small electronegativity difference results in a predominantly covalent bond, while a large difference pushes the bond towards being more ionic in nature. When the electronegativity difference is significant enough (often considered greater than 1.7 on the Pauling scale), the bond is generally classified as ionic.

Electronegativity Trends: The Periodic Table as Your Guide

Electronegativity isn’t a random property; it follows predictable trends across the periodic table. These trends are invaluable for quickly assessing the relative electronegativity of elements and predicting bond types.

Electronegativity Chart

Electronegativity Chart

Alt text: Periodic table chart showing electronegativity values of elements. Electronegativity increases across periods from left to right and decreases down groups.

As you move across a period (from left to right) on the periodic table, electronegativity generally increases. This is because, across a period, the number of protons in the nucleus increases (increasing nuclear charge), while the number of electron shells remains the same. The increased nuclear charge exerts a stronger pull on the valence electrons, making the atom more inclined to attract electrons in a bond, thus increasing electronegativity.

Conversely, as you move down a group (from top to bottom) in the periodic table, electronegativity generally decreases. While the nuclear charge also increases down a group, the number of electron shells also increases significantly. These additional inner electron shells shield the valence electrons from the full positive charge of the nucleus, reducing the effective nuclear charge experienced by the valence electrons. Furthermore, the atomic size increases down a group, meaning valence electrons are further from the nucleus. Both these factors weaken the atom’s ability to attract electrons in a bond, resulting in a decrease in electronegativity.

Factors Influencing Electronegativity

While the periodic table trends provide a general overview, several factors fine-tune an element’s electronegativity:

1. Atomic Size:

Atomic size and electronegativity have an inverse relationship. Larger atoms tend to have lower electronegativity values. This is because in larger atoms, the valence electrons are located further away from the positively charged nucleus. This increased distance weakens the attractive force between the nucleus and the valence electrons, making it less effective at attracting additional electrons in a chemical bond.

2. Nuclear Charge:

Nuclear charge, which is determined by the number of protons in the nucleus, has a direct relationship with electronegativity. A greater nuclear charge leads to a higher electronegativity. A stronger positive charge in the nucleus exerts a greater attractive force on electrons, including those involved in chemical bonds. This enhanced attraction increases the atom’s ability to draw electrons towards itself, resulting in higher electronegativity.

3. Substituent Effects:

The chemical environment surrounding an atom can also influence its electronegativity. Substituents, which are atoms or groups of atoms attached to a central atom, can alter the electron density around that atom and thus affect its electronegativity. For example, consider carbon in CF₃I and CH₃I. The highly electronegative fluorine atoms in CF₃I pull electron density away from the carbon atom, making it relatively more positive and thus more electronegative compared to the carbon atom in CH₃I, which is bonded to less electronegative hydrogen atoms. These subtle shifts in electronegativity due to substituents can have significant consequences for the chemical behavior of molecules.

Frequently Asked Questions about Electronegativity

Q1: What is the most accurate definition of electronegativity?

Electronegativity is best defined as the ability of an atom within a molecule to attract shared electrons in a chemical bond towards itself. The Pauling scale is the most widely used scale for quantifying electronegativity, assigning Fluorine a value of 4.0 and Cesium and Francium, the least electronegative elements, values around 0.7.

Q2: What constitutes high electronegativity?

High electronegativity is generally associated with elements located towards the top right of the periodic table, with values approaching 4.0 on the Pauling scale. These elements, like Fluorine and Oxygen, strongly attract electrons in chemical bonds.

Q3: What does electronegativity difference tell us?

The electronegativity difference between two bonded atoms is a crucial indicator of bond character. A large difference (greater than 1.7) suggests an ionic bond. A moderate difference (between 0.4 and 1.7) indicates a polar covalent bond. A small or negligible difference (less than 0.4) points towards a nonpolar covalent bond.

Q4: How does electronegativity differ from electron affinity?

While both electronegativity and electron affinity relate to an atom’s attraction for electrons, they are distinct concepts. Electron affinity is the energy change that occurs when an electron is added to a neutral atom in the gaseous phase to form a negative ion (anion). It’s a measurable, quantitative value for an isolated atom. Electronegativity, on the other hand, is a qualitative, relative measure of an atom’s ability to attract electrons within a chemical bond in a molecule.

Q5: Is electronegativity a relative property?

Yes, electronegativity is inherently a relative property. It describes an atom’s ability to attract electrons in comparison to other atoms in a chemical bond. It’s not an absolute value but rather a comparative measure of electron-attracting power.

Q6: How does electronegativity change across a period in the periodic table?

Electronegativity increases as you move from left to right across a period in the periodic table. This trend is due to the increasing effective nuclear charge and decreasing atomic size across a period, both of which enhance the atom’s ability to attract electrons.

Q7: How does electronegativity change down a group in the periodic table?

Electronegativity decreases as you move down a group in the periodic table. This is primarily attributed to the increasing atomic size and increased electron shielding down a group, which weaken the atom’s hold on valence electrons and reduce its ability to attract electrons in a bond.

Q8: Which elements are the most and least electronegative in the periodic table?

Fluorine (F) is the most electronegative element, and Cesium (Cs) is the least electronegative element in the periodic table.

Q9: How does an element’s electronegativity affect its bonding behavior?

Electronegativity profoundly influences an element’s bonding behavior. Highly electronegative elements tend to form ionic bonds with elements of low electronegativity and polar covalent bonds with elements of intermediate electronegativity. The degree of polarity and ionic character in a bond is directly dictated by the electronegativity difference.

Q10: How does atomic size impact electronegativity?

Larger atomic size generally leads to lower electronegativity. In larger atoms, valence electrons are further from the nucleus and experience a weaker attractive force, reducing the atom’s ability to attract electrons in a chemical bond.

Electronegativity is a cornerstone concept in chemistry, providing a powerful framework for understanding chemical bonding, molecular properties, and reactivity. By grasping the principles of electronegativity and its periodic trends, you unlock a deeper understanding of the fascinating world of chemical interactions.