For centuries, heredity stood as one of nature’s most profound enigmas. The reason for this mystification lay in the sex cells – the very conduits of inheritance between generations – often being invisible to the naked eye. It wasn’t until the advent of the microscope in the 17th century and the subsequent revelation of sex cells that the fundamental principles of heredity began to emerge. Prior to this scientific leap, thinkers like the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle, in the 4th century BC, posited theories suggesting an unequal contribution from male and female parents. Aristotle believed the female provided the “matter,” while the male contributed the “motion.” Similarly, the Institutes of Manu, composed in India between 100 and 300 AD, likened the female’s role to that of a field and the male’s to a seed, stating that new beings arose from the “united operation of the seed and the field.”

In reality, both parents contribute equally to the hereditary blueprint. On average, offspring bear resemblance to their mothers just as much as to their fathers. However, the size and structure of male and female sex cells can indeed be drastically different, with an egg cell’s mass sometimes dwarfing that of a spermatozoon by millions of times.

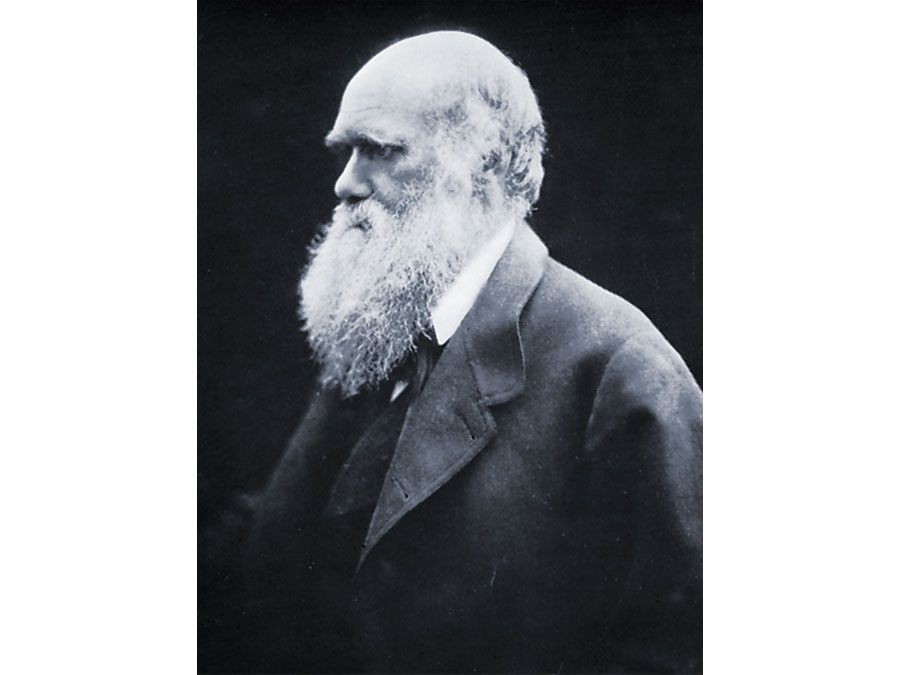

Ancient Babylonians possessed practical knowledge of plant heredity, understanding the necessity of pollen from a male date palm tree for fertilizing the pistils of a female tree to yield fruit. In 1694, German botanist Rudolph Jacob Camerarius corroborated this understanding in corn (maize). Later, Swedish botanist and explorer Carolus Linnaeus in 1760, followed by German botanist Josef Gottlieb Kölreuter in works spanning from 1761 to 1798, meticulously documented crosses between plant varieties and species. Their findings revealed that hybrids generally exhibited characteristics intermediate to their parents. While some traits might lean more towards one parent, others might favor the other. Kölreuter notably compared offspring from reciprocal crosses – variety A as female to variety B as male, and vice versa. The striking similarity of hybrid progeny from these reciprocal crosses challenged Aristotle’s notion, suggesting that hereditary contributions were, in fact, equal from both parents. The 19th century witnessed a surge in plant hybridization experiments, largely confirming the intermediate nature of hybrids. These investigations inadvertently amassed crucial data that would later pave the way for Gregor Mendel’s groundbreaking rules and the foundation of gene theory. Yet, Mendel’s predecessors seemed to have missed the significance of the accumulating data. The prevalent intermediacy in hybrids seemed to align with the popular belief that heredity was transmitted through “blood,” a concept embraced by many 19th-century biologists, including Charles Darwin.

Charles Darwin

Charles Darwin, carbon-print photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, 1868.

The Blood Theory of Heredity: A Pervasive Misconception

The “blood” theory of heredity, while perhaps too simplistic to be considered a formal scientific theory, was deeply embedded in folklore, predating scientific biology. Phrases like “half-blood,” “new blood,” and “blue blood” are linguistic relics of this pervasive idea. It’s crucial to understand that this theory wasn’t about the literal red liquid in blood vessels as the carrier of heredity. Instead, it embodied the belief that a parent transmitted their entire suite of characteristics to each child, resulting in a child’s hereditary makeup being a blend or alloy of traits from parents, grandparents, and distant ancestors. This notion appealed particularly to those who took pride in their “noble” or distinguished lineage.

However, the blood theory encountered significant challenges. Observations revealed children possessing traits absent in both parents but present in other relatives or more remote ancestors. Even more commonly, siblings, despite familial resemblances, exhibited distinct differences in various characteristics. How could the same parental “blood” produce such diverse hereditary outcomes in their offspring?

Mendel’s Groundbreaking Discoveries: Moving Beyond the Blood Theory

Gregor Mendel effectively dismantled the blood theory. His experiments demonstrated several key principles: (1) heredity is transmitted through discrete units, which we now know as genes, that do not blend but segregate; (2) parents contribute only half of their genes to each offspring, and these sets of genes vary between siblings; and (3) consequently, siblings, with the exception of identical twins, inherit different sets of genes even from the same parents. Mendel’s work revealed that even if an ancestor’s prominence was genetically determined, their descendants, especially distant ones, might not inherit those specific “good” genes. In sexually reproducing organisms, including humans, each individual possesses a unique hereditary endowment.

Lamarckism and the Erroneous Inheritance of Acquired Traits

Lamarckism, named after the 19th-century French biologist Jean-Baptiste de Monet, chevalier de Lamarck, proposed that characteristics acquired during an organism’s lifetime could be passed down to its progeny. In modern terms, this suggests that environmental modifications to the phenotype would induce corresponding changes in the genotype. For example, proponents of Lamarckism might argue that the offspring of individuals who engaged in extensive physical exercise would find exercise inherently easier or even unnecessary. Lamarck, and even Darwin to some extent, initially accepted the inheritance of acquired traits.

However, German biologist August Weismann challenged this notion. His famous experiments in the late 1890s, involving the amputation of tails in successive generations of mice, demonstrated that this acquired modification neither caused the tails to disappear nor even shorten in subsequent generations. Weismann concluded that an organism’s hereditary material, which he termed germ plasm, was separate and protected from influences originating from the rest of the body, the somatoplasm or soma. While related to the genotype-phenotype concepts, germ plasm and somatoplasm are not entirely synonymous and should not be confused with them.

The rejection of acquired trait inheritance does not imply that genes are immutable to environmental factors. Mutagens like X-rays can indeed alter genes, and populations’ genotypes can be shaped by selection. It simply signifies that physical and intellectual attributes acquired by parents during their lives are not genetically transmitted to their children.

Persistent Superstitions: Prepotency, Prenatal Influences, and Telegony

Linked to these misconceptions are beliefs in “prepotency”—the idea that certain individuals exert a stronger hereditary influence on their offspring than others—and “prenatal influences” or “maternal impressions”—the notion that experiences during pregnancy impact the constitution of the unborn child. The antiquity of these beliefs is evident in the Book of Genesis, where Jacob is described as producing spotted or striped sheep and goats by showing striped rods to the flocks during breeding.

Another such superstition is “telegony,” dating back to Aristotle. Telegony proposed that an individual’s heredity could be influenced not only by their father but also by previous mates of the female parent from prior pregnancies. Even Darwin, as late as 1868, discussed a case of telegony involving a mare bred to a zebra and subsequently to an Arabian stallion, resulting in a foal with faint leg stripes. However, the simpler explanation is that such stripes naturally occur in some horse breeds.

The Lysenko Affair: A Modern Example of Misguided Heredity Theories

All these beliefs, from the inheritance of acquired traits to telegony, are now classified as superstitions. They fail rigorous experimental scrutiny and contradict our understanding of heredity mechanisms and the predictable nature of genetic material. Despite this, some individuals still adhere to these outdated ideas. Certain animal breeders, for instance, take telegony seriously, questioning the purity of offspring if their mothers have previously mated with males of different breeds, even if the parents are “purebred.”

Tragically, Soviet biologist and agronomist Trofim Denisovich Lysenko managed to establish his Lamarckian-inspired theories as official dogma in the Soviet Union for nearly 25 years (roughly 1938-1963). This led to the suppression of orthodox genetics research and education. Lysenko and his followers published numerous works purportedly proving their claims, effectively rejecting a century of biological advancements. Lysenkoism was ultimately discredited in 1964.

In conclusion, the journey to understanding “What Is Heredity” has been a long and fascinating one, moving from prescientific speculations and folklore to the rigorous science of modern genetics. While ancient thinkers laid early groundwork by observing patterns of inheritance, it was the scientific method, particularly the work of Mendel, Weismann, and subsequent geneticists, that truly illuminated the mechanisms of heredity and dispelled long-held misconceptions. Today, genetics continues to advance, building upon this rich history to unlock ever deeper secrets of inheritance and life itself.