What Is Historiography? It’s the study of how history is written, interpreted, and understood, including the evolution of historical methods. WHAT.EDU.VN provides free answers to your questions, offering insights into this captivating field, along with historical analysis, and critical examination.

1. Understanding the Essence of Historiography

Historiography encompasses more than just the writing of history it involves a critical examination of the sources, methods, and interpretations employed by historians. It delves into the theory and history of historical writing itself. What is historiography’s central focus? Its central focus is the evolution of historical thought and the ways in which historians have approached their craft over time.

1.1. The Core Components of Historiography

Historiography involves several core components, each contributing to a deeper understanding of how history is constructed and interpreted. These include:

- Source Criticism: Examining the reliability and authenticity of historical sources.

- Methodology: Analyzing the methods and techniques used by historians in their research and writing.

- Interpretation: Evaluating the different interpretations of historical events and figures.

- Historical Context: Understanding the social, cultural, and political context in which historical works were produced.

- Historiographical Traditions: Investigating different schools of historical thought and their influence.

1.2. Why Historiography Matters

Understanding historiography is crucial for several reasons. It allows us to:

- Appreciate the Subjectivity of History: Recognize that history is not a neutral or objective account of the past, but rather a constructed narrative shaped by the historian’s perspective and biases.

- Evaluate Historical Claims: Critically assess historical arguments and interpretations, considering the evidence and methods used to support them.

- Understand the Evolution of Historical Thought: Trace the development of historical ideas and approaches over time, recognizing how they have been influenced by social, cultural, and political changes.

- Engage with Diverse Perspectives: Explore different interpretations of the past, recognizing that there are often multiple valid perspectives on historical events.

- Promote Responsible Historical Writing: Encourage historians to be self-aware and transparent about their methods and biases, and to strive for accuracy and objectivity in their work.

2. A Journey Through the History of Historiography

The field of historiography has evolved significantly over time, reflecting changing social, cultural, and intellectual trends. Tracing this evolution provides valuable insights into the nature of history itself.

2.1. Ancient Historiography: Laying the Foundation

Ancient civilizations produced some of the earliest forms of historical writing. These early historians often focused on recording the deeds of rulers and the events of wars, with a strong emphasis on moral lessons and divine intervention.

2.1.1. Key Figures and Works

- Herodotus: Known as the “father of history,” Herodotus sought to understand the causes of the Greco-Persian Wars by collecting and recording information from various sources.

- Thucydides: A more critical and analytical historian, Thucydides focused on the Peloponnesian War, emphasizing human agency and political factors.

- Livy: A Roman historian who wrote a comprehensive history of Rome, emphasizing its rise to power and its moral virtues.

2.1.2. Characteristics of Ancient Historiography

- Emphasis on Narrative: Ancient historians focused on telling compelling stories, often with a moral or political purpose.

- Limited Source Criticism: Ancient historians often relied on oral traditions and legends, with limited critical evaluation of their sources.

- Focus on Elites: Ancient history typically focused on the actions of rulers, generals, and other prominent figures, with less attention to the lives of ordinary people.

- Providential Interpretation: Ancient historians often attributed events to the will of the gods or to fate.

2.2. Medieval Historiography: God and the Past

Medieval historiography was heavily influenced by Christianity, with a focus on understanding history as part of God’s plan for humanity. Chroniclers and annalists recorded events in chronological order, often with a strong emphasis on religious themes.

2.2.1. Key Figures and Works

- Augustine of Hippo: His “City of God” presented a theological interpretation of history, arguing that earthly events were ultimately subordinate to God’s divine purpose.

- Bede: An English monk who wrote the “Ecclesiastical History of the English People,” providing a valuable account of the early history of Christianity in England.

- Gregory of Tours: A Frankish bishop who wrote the “History of the Franks,” offering insights into the political and social life of Merovingian Gaul.

2.2.2. Characteristics of Medieval Historiography

- Religious Interpretation: Medieval historians saw history as a divinely ordained process, with events interpreted in light of Christian theology.

- Chronicles and Annals: Medieval historical writing often took the form of chronicles or annals, recording events in chronological order.

- Focus on Religious Institutions: Medieval historians paid close attention to the history of the Church and other religious institutions.

- Moralistic Tone: Medieval historical writing often emphasized moral lessons and the importance of religious piety.

2.3. Renaissance Historiography: Rediscovering the Past

The Renaissance marked a revival of interest in classical learning and a new emphasis on humanism. Renaissance historians sought to emulate the style and methods of ancient historians, with a focus on human agency and political analysis.

2.3.1. Key Figures and Works

- Niccolò Machiavelli: His “History of Florence” offered a pragmatic and secular analysis of political events, emphasizing the role of power and self-interest.

- Francesco Guicciardini: Another Florentine historian, Guicciardini wrote a detailed history of Italy, focusing on political and diplomatic events.

- Leonardo Bruni: A humanist scholar who translated and interpreted classical texts, contributing to a renewed interest in ancient history.

2.3.2. Characteristics of Renaissance Historiography

- Humanism: Renaissance historians emphasized human agency and the importance of human reason.

- Political Analysis: Renaissance historians focused on political events and the actions of rulers and statesmen.

- Secularism: Renaissance historians often adopted a more secular approach to history, downplaying the role of divine intervention.

- Classical Influence: Renaissance historians sought to emulate the style and methods of ancient historians.

2.4. Enlightenment Historiography: Reason and Progress

The Enlightenment emphasized reason, progress, and individual liberty. Enlightenment historians sought to apply scientific methods to the study of history, with a focus on understanding the underlying causes of events and the progress of civilization.

2.4.1. Key Figures and Works

- Edward Gibbon: His “Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire” offered a sweeping account of Roman history, emphasizing the role of internal decay and external pressures.

- Voltaire: A French philosopher and historian who advocated for religious toleration and criticized superstition and fanaticism.

- David Hume: A Scottish philosopher and historian who emphasized the importance of empirical evidence and skepticism.

2.4.2. Characteristics of Enlightenment Historiography

- Reason and Empiricism: Enlightenment historians emphasized the importance of reason and empirical evidence in understanding the past.

- Progress: Enlightenment historians believed in the possibility of human progress and sought to identify the factors that contributed to it.

- Secularism: Enlightenment historians adopted a secular approach to history, rejecting religious explanations and emphasizing human agency.

- Universal History: Enlightenment historians sought to write universal histories that would encompass the entire human experience.

2.5. 19th-Century Historiography: The Rise of Professional History

The 19th century saw the rise of history as a professional discipline, with the establishment of university departments and the development of rigorous methods of research and analysis. Historians began to emphasize objectivity, source criticism, and the reconstruction of the past “as it actually was.”

2.5.1. Key Figures and Works

- Leopold von Ranke: Considered the founder of modern historical scholarship, Ranke emphasized the importance of archival research and the reconstruction of the past “wie es eigentlich gewesen ist” (as it actually was).

- Jules Michelet: A French historian who wrote passionate and evocative accounts of French history, emphasizing the role of the people.

- Thomas Babington Macaulay: A British historian who wrote a popular history of England, emphasizing progress and the triumph of liberal values.

2.5.2. Characteristics of 19th-Century Historiography

- Professionalism: History became a professional discipline, with the establishment of university departments and the development of rigorous methods of research and analysis.

- Objectivity: Historians sought to achieve objectivity in their work, striving to present a neutral and unbiased account of the past.

- Source Criticism: Historians emphasized the importance of critically evaluating historical sources, assessing their reliability and authenticity.

- Nationalism: 19th-century historiography was often influenced by nationalism, with historians seeking to construct national identities and promote national pride.

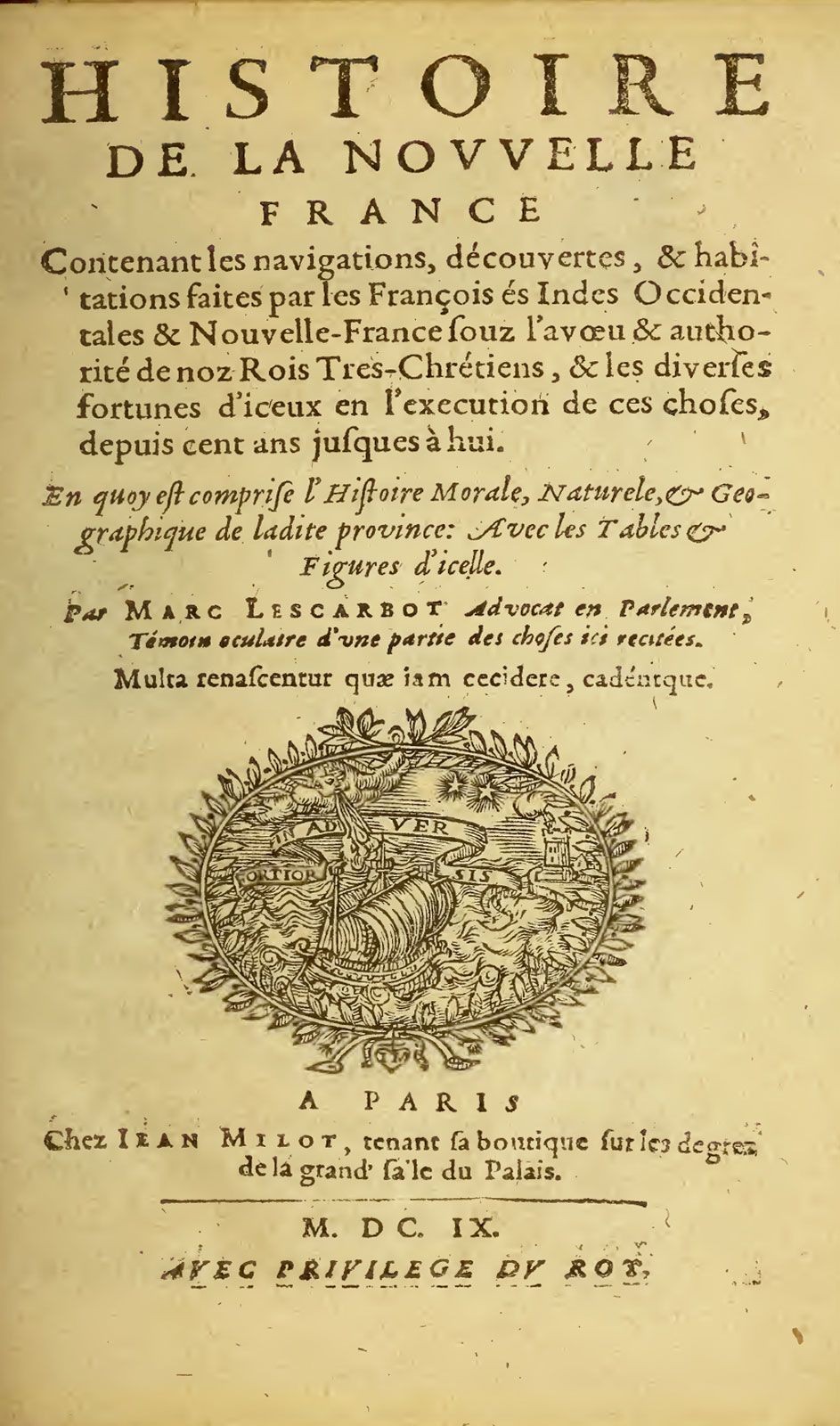

Title page of Histoire de la Nouvelle France (1609; History of New France) by Marc Lescarbot.

Title page of Histoire de la Nouvelle France (1609; History of New France) by Marc Lescarbot.

2.6. 20th-Century Historiography: New Perspectives and Challenges

The 20th century witnessed a proliferation of new approaches to history, including social history, cultural history, gender history, and postcolonial history. Historians challenged traditional notions of objectivity and emphasized the role of power, ideology, and identity in shaping the past.

2.6.1. Key Figures and Works

- Marc Bloch: A French historian and co-founder of the Annales School, Bloch emphasized the importance of interdisciplinary approaches and the study of social and economic structures.

- Fernand Braudel: Another prominent member of the Annales School, Braudel focused on long-term historical processes and the relationship between humans and their environment.

- E.P. Thompson: A British historian who wrote “The Making of the English Working Class,” a seminal work of social history that emphasized the agency of ordinary people.

- Michel Foucault: A French philosopher and historian who explored the relationship between power, knowledge, and discourse in shaping historical understanding.

- Joan Wallach Scott: An American historian who has made significant contributions to gender history and feminist theory.

2.6.2. Characteristics of 20th-Century Historiography

- Social History: A focus on the lives and experiences of ordinary people, rather than just elites.

- Cultural History: An interest in the beliefs, values, and practices of different cultures and societies.

- Gender History: An examination of the role of gender in shaping historical events and social structures.

- Postcolonial History: A critical analysis of the legacy of colonialism and its impact on formerly colonized societies.

- Emphasis on Interpretation: A recognition that history is not a neutral or objective account of the past, but rather a constructed narrative shaped by the historian’s perspective and biases.

2.7. 21st-Century Historiography: Digital Age and Global Perspectives

The 21st century presents new opportunities and challenges for historiography. The rise of digital technology has made vast amounts of information more accessible than ever before, but it has also raised questions about the reliability and authenticity of online sources. Globalization has led to a greater awareness of diverse perspectives and the need for more inclusive and transnational approaches to history.

2.7.1. Emerging Trends

- Digital History: The use of digital tools and methods to research, analyze, and present historical information.

- Global History: A focus on transnational connections and interactions, rather than just national or regional histories.

- Environmental History: An examination of the relationship between humans and the environment over time.

- Public History: The application of historical knowledge and skills to public audiences, such as museums, archives, and community organizations.

- Increased Interdisciplinarity: Greater collaboration between historians and scholars from other disciplines, such as sociology, anthropology, and literature.

3. Key Concepts in Historiography

Understanding the key concepts in historiography is essential for engaging with historical scholarship and critically evaluating historical arguments.

3.1. Objectivity vs. Subjectivity

One of the central debates in historiography concerns the possibility of objectivity in historical writing. Can historians truly present a neutral and unbiased account of the past, or are they inevitably influenced by their own perspectives and biases?

- Objectivity: The idea that historians can and should strive to present a neutral and unbiased account of the past, based on evidence and reason.

- Subjectivity: The recognition that historians are inevitably influenced by their own perspectives, biases, and values, which shape their interpretation of the past.

3.2. Historical Sources

Historical sources are the raw materials that historians use to reconstruct the past. These sources can take many forms, including:

- Primary Sources: Documents or artifacts created during the period under study, such as letters, diaries, government records, and photographs.

- Secondary Sources: Accounts of the past written by historians or other scholars, based on their analysis of primary sources.

- Oral Sources: Accounts of the past passed down through oral traditions, such as stories, songs, and interviews.

- Material Culture: Physical objects that provide insights into the past, such as tools, clothing, and buildings.

3.3. Historical Interpretation

Historical interpretation is the process of making sense of historical sources and constructing a narrative of the past. Different historians may interpret the same sources in different ways, leading to different interpretations of historical events and figures.

- Factors Influencing Interpretation: Historians’ interpretations are influenced by a variety of factors, including their own perspectives, biases, values, and the prevailing intellectual and cultural climate.

- Importance of Context: Understanding the historical context in which sources were produced is crucial for interpreting them accurately.

- Multiple Perspectives: Recognizing that there are often multiple valid perspectives on historical events is essential for a nuanced understanding of the past.

3.4. Historical Causation

Historical causation refers to the process of identifying the causes and effects of historical events. Historians often debate the relative importance of different factors in causing a particular event, such as economic, social, political, or cultural factors.

- Multiple Causes: Most historical events have multiple causes, and it is often difficult to isolate a single cause as the most important.

- Long-Term vs. Short-Term Causes: Historians often distinguish between long-term causes, which create the conditions for an event to occur, and short-term causes, which trigger the event itself.

- Unintended Consequences: Historical events often have unintended consequences, which can be difficult to predict or control.

3.5. Historical Significance

Historical significance refers to the importance or relevance of a particular event or figure in the past. Historians often debate which events and figures are most significant and why.

- Criteria for Significance: Historians use various criteria to assess historical significance, such as the impact of an event on subsequent events, its relevance to contemporary issues, and its ability to shed light on the human condition.

- Changing Significance: The significance of historical events and figures can change over time, as new perspectives and interpretations emerge.

- Subjectivity of Significance: The determination of historical significance is often subjective, reflecting the values and priorities of the historian.

4. Schools of Thought in Historiography

Different schools of thought in historiography offer different approaches to understanding and writing about the past. Each school has its own set of assumptions, methods, and priorities.

4.1. Rankean Historiography

Rankean historiography, named after Leopold von Ranke, emphasizes the importance of objectivity, source criticism, and the reconstruction of the past “as it actually was.” Rankean historians seek to present a neutral and unbiased account of the past, based on rigorous archival research and careful analysis of primary sources.

- Key Principles: Objectivity, source criticism, archival research, and the reconstruction of the past “as it actually was.”

- Strengths: Emphasis on rigor and accuracy, commitment to evidence-based analysis.

- Weaknesses: Can be overly focused on political and diplomatic history, neglecting social and cultural factors; may downplay the role of interpretation and subjectivity.

4.2. Marxist Historiography

Marxist historiography, inspired by the writings of Karl Marx, emphasizes the role of economic and social forces in shaping history. Marxist historians focus on class struggle, modes of production, and the relationship between the base (economic structure) and the superstructure (culture, politics, and ideology).

- Key Principles: Class struggle, modes of production, base and superstructure, historical materialism.

- Strengths: Focus on social and economic factors, attention to the experiences of ordinary people, critical analysis of power structures.

- Weaknesses: Can be overly deterministic, neglecting the role of individual agency and cultural factors; may be biased towards certain political ideologies.

4.3. Annales School

The Annales School, founded in France in the 20th century, emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches, long-term historical processes, and the study of social and economic structures. Annales historians often focus on the relationship between humans and their environment and the mentalités (collective attitudes and beliefs) of different societies.

- Key Principles: Interdisciplinarity, long-term historical processes (la longue durée), social and economic structures, mentalités, and the relationship between humans and their environment.

- Strengths: Broad and interdisciplinary approach, attention to social and economic factors, focus on long-term historical processes.

- Weaknesses: Can be overly focused on structures, neglecting the role of individual agency and political events; may be difficult to synthesize diverse sources and perspectives.

4.4. Poststructuralist Historiography

Poststructuralist historiography, influenced by the writings of Michel Foucault and other poststructuralist thinkers, emphasizes the role of power, knowledge, and discourse in shaping historical understanding. Poststructuralist historians challenge traditional notions of objectivity and truth, arguing that history is always constructed and interpreted through particular power relations and discursive frameworks.

- Key Principles: Power, knowledge, discourse, deconstruction, and the social construction of reality.

- Strengths: Critical analysis of power structures, attention to the role of language and discourse, emphasis on the subjectivity of historical interpretation.

- Weaknesses: Can be overly relativistic, undermining the possibility of objective truth; may be difficult to connect theory with empirical evidence; can be jargon-heavy and inaccessible to a wider audience.

4.5. Gender History

Gender history examines the role of gender in shaping historical events and social structures. Gender historians challenge traditional, male-centered accounts of the past and seek to recover the experiences and perspectives of women and other marginalized groups.

- Key Principles: Gender as a social construct, the intersection of gender with other forms of identity (race, class, sexuality), the recovery of women’s experiences, and the analysis of power relations.

- Strengths: Attention to the experiences of women and other marginalized groups, critical analysis of gender stereotypes, and insights into the social construction of identity.

- Weaknesses: Can be overly focused on gender, neglecting other important factors; may be difficult to generalize from specific case studies; can be politically charged and divisive.

5. Practical Applications of Historiography

Historiography is not just an abstract academic exercise it has practical applications in various fields, from education to public policy.

5.1. Education

Understanding historiography is essential for students of history, as it allows them to critically evaluate historical sources, arguments, and interpretations. Historiography helps students to:

- Develop Critical Thinking Skills: By examining the methods and biases of historians, students learn to think critically about historical claims and interpretations.

- Understand the Complexity of the Past: Historiography helps students to appreciate the complexity and ambiguity of the past, recognizing that there are often multiple valid perspectives on historical events.

- Engage with Diverse Perspectives: By exploring different historiographical approaches, students learn to engage with diverse perspectives and challenge their own assumptions.

- Become More Informed Citizens: Understanding history is essential for informed citizenship, as it provides context for understanding contemporary issues and challenges.

5.2. Public History

Public history involves the application of historical knowledge and skills to public audiences, such as museums, archives, and community organizations. Historiography can help public historians to:

- Develop Engaging and Accurate Exhibits: By understanding the historiography of a particular topic, public historians can develop exhibits that are both engaging and accurate.

- Interpret Historical Sites and Monuments: Historiography can provide insights into the meaning and significance of historical sites and monuments, helping public historians to interpret them for visitors.

- Engage with Community Stakeholders: Public historians often work with community stakeholders who have diverse perspectives on the past. Historiography can help them to navigate these different perspectives and develop inclusive and respectful interpretations.

- Promote Historical Awareness and Understanding: Public history plays an important role in promoting historical awareness and understanding among the general public.

5.3. Public Policy

History can inform public policy by providing context for understanding contemporary issues and challenges. Historiography can help policymakers to:

- Learn from Past Mistakes: By studying the history of past policies, policymakers can learn from past mistakes and avoid repeating them.

- Understand the Long-Term Consequences of Policies: History can help policymakers to understand the long-term consequences of their decisions, both intended and unintended.

- Identify Patterns and Trends: By analyzing historical data, policymakers can identify patterns and trends that may be relevant to contemporary issues.

- Engage with Diverse Perspectives: History can help policymakers to engage with diverse perspectives and understand the social, cultural, and economic context in which policies are implemented.

6. Common Misconceptions About Historiography

Several misconceptions about historiography can hinder a proper understanding of the discipline. Addressing these misconceptions is crucial for promoting a more accurate and nuanced view of history.

6.1. Historiography is Only for Historians

While historiography is an essential tool for historians, its value extends beyond the academic realm. Anyone interested in understanding the past and its influence on the present can benefit from studying historiography. It provides a framework for critical thinking and evaluating different accounts of historical events.

6.2. Historiography is About Memorizing Names and Dates

Historiography is not about rote memorization of historical facts. Instead, it focuses on understanding how historical knowledge is produced, interpreted, and used. It involves analyzing the methods, biases, and perspectives of historians, rather than simply memorizing their conclusions.

6.3. Historiography Makes History Too Subjective

While historiography acknowledges the subjectivity inherent in historical writing, it does not necessarily undermine the possibility of objective truth. Instead, it encourages historians to be more self-aware and transparent about their methods and biases, and to strive for accuracy and fairness in their interpretations.

6.4. Historiography is Only Relevant to Ancient History

Historiography is relevant to all periods of history, not just ancient history. Every historical period has its own historiography, with different schools of thought, methods, and interpretations. Understanding the historiography of a particular period is essential for understanding the history of that period.

6.5. Historiography is a Modern Invention

While the term “historiography” may be relatively recent, the practice of reflecting on the writing of history dates back to ancient times. Ancient historians like Herodotus and Thucydides were already concerned with issues of source criticism, interpretation, and historical causation.

7. Frequently Asked Questions About Historiography

Here are some frequently asked questions about historiography, along with detailed answers:

| Question | Answer |

|---|---|

| What is the difference between history and historiography? | History is the study of the past, while historiography is the study of how history is written and interpreted. Historiography examines the methods, sources, and biases of historians, as well as the evolution of historical thought over time. |

| What are the main sources used in historiography? | Historiography relies on a variety of sources, including primary sources (documents and artifacts from the past), secondary sources (historical accounts written by historians), and historiographical works (studies of historical writing). |

| How does historiography help us understand the past better? | Historiography helps us understand the past better by revealing the complexities and nuances of historical interpretation. It allows us to critically evaluate historical claims, recognize the influence of different perspectives, and appreciate the ever-evolving nature of historical knowledge. |

| What are some of the major debates in historiography? | Major debates in historiography include the possibility of objectivity, the role of ideology, the importance of social and economic factors, and the relationship between history and memory. |

| How has historiography changed over time? | Historiography has changed dramatically over time, reflecting changing social, cultural, and intellectual trends. From ancient chronicles to modern social history, the methods, sources, and interpretations of historians have evolved significantly. |

| What is the role of theory in historiography? | Theory plays an important role in historiography by providing frameworks for understanding and interpreting the past. Different theoretical approaches, such as Marxism, feminism, and poststructuralism, offer different perspectives on historical events and processes. |

| How does historiography relate to other disciplines? | Historiography is closely related to other disciplines, such as philosophy, literature, sociology, and anthropology. Historians often draw on insights from these disciplines to enrich their understanding of the past. |

| What are some of the ethical considerations in historiography? | Ethical considerations in historiography include the responsibility to accurately represent historical sources, to avoid plagiarism and fabrication, and to be transparent about one’s own biases and perspectives. |

| How can historiography be used to promote social justice? | Historiography can be used to promote social justice by challenging dominant narratives, recovering the experiences of marginalized groups, and promoting critical awareness of power structures. |

| What are the challenges facing historiography today? | Challenges facing historiography today include the rise of misinformation and disinformation, the increasing politicization of history, and the need to engage with diverse perspectives and global issues. |

8. Resources for Further Exploration

For those interested in delving deeper into the world of historiography, here are some valuable resources:

- Books:

- “What is History?” by E.H. Carr

- “The Practice of History” by G.R. Elton

- “History and Theory” by various authors

- Journals:

- History and Theory

- The American Historical Review

- The Journal of Modern History

- Websites:

- American Historical Association (AHA)

- Royal Historical Society (RHS)

- WHAT.EDU.VN (for answering any question)

9. Conclusion: Historiography as a Dynamic and Evolving Field

Historiography is a dynamic and evolving field that plays a crucial role in shaping our understanding of the past. By critically examining the methods, sources, and interpretations of historians, we can gain a deeper appreciation for the complexity and ambiguity of history. Understanding historiography is essential for students, scholars, and anyone interested in engaging with the past in a meaningful way.

Ready to Explore Further?

Do you have questions about historiography or any other topic? Don’t hesitate to ask WHAT.EDU.VN! Our platform offers free answers and expert insights to help you understand the world around you.

Visit WHAT.EDU.VN today and start exploring!

Contact us:

Address: 888 Question City Plaza, Seattle, WA 98101, United States

Whatsapp: +1 (206) 555-7890

Website: what.edu.vn