Hypersexuality, a term increasingly used in modern discourse, particularly within clinical settings, refers to a condition characterized by an amplified sexual drive that leads individuals to seek sexual gratification in ways that are often inappropriate, uncontrollable, and ultimately unsatisfying. It’s a complex issue that goes beyond simply having a high libido; it involves distress and impairment in various aspects of life. This article delves into the definition of hypersexuality, exploring its historical roots, clinical classifications, potential causes, and proposed diagnostic frameworks to provide a comprehensive understanding of this often-misunderstood condition.

Historical Roots: Tracing Back to Nymphomania and Satyriasis

The concept of hypersexuality, while modern in its terminology, has roots in historical understandings of excessive sexual desire, previously labeled as nymphomania in women and satyriasis in men. These older terms, drawn from Greek mythology, reflect ancient attempts to categorize and explain what was perceived as an abnormal exaggeration of sexual impulses.

Nymphomania, derived from the myth of nymphs – beautiful maidens known for their seductive allure and pursuit of sexual partners – described an uncontrollable sexual desire in women. Similarly, satyriasis, named after satyrs – mythical creatures depicted as half-man, half-animal, and symbols of lust – denoted excessive sexual desire in men.

These terms, while rooted in folklore, highlight a long-standing recognition of the phenomenon we now understand as hypersexuality. Physician Giambatista De Bienville’s 1771 treatise, “Nymphomania. Treatise on Uterine Fury,” marks an early attempt to clinically define and understand this condition, demonstrating its presence in medical thought for centuries. Modern hypersexuality seeks to replace these gendered and mythologically charged terms with a more clinically grounded and inclusive understanding.

Clinical Definitions: Navigating ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR

Today, hypersexuality is recognized within the framework of contemporary psychiatric classifications, appearing in both the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR). These manuals, while both aiming to categorize mental health conditions, approach hypersexuality with slight variations, reflecting the ongoing debate and evolving understanding within the scientific community.

The ICD-11, published by the World Health Organization, classifies hypersexuality under “Sexual Compulsive Behaviour Disorder” (code 6C72). This classification emphasizes the compulsive nature of the behavior and its impact on overall functioning. The diagnostic criteria in ICD-11 for Sexual Compulsive Behaviour Disorder include:

(A) For at least six months, recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual urges, or sexual behaviour in association with three or more of the following:

- Time spent in repetitive sexual fantasies, impulses, or behaviours that interfere with other important (non-sexual) goals, activities, or obligations.

- Repetitive engagement in sexual fantasies, impulses, or behaviours in response to dysphoric mood states (e.g., anxiety, depression, boredom, or irritability).

- Repetitive engagement in sexual fantasies, impulses, or behaviours in response to stressful life events.

- Repetitive but unsuccessful efforts to control or significantly reduce such fantasies, impulses, or behaviours.

- Repetitive engagement in sexual behaviours, disregarding the risk of physical or emotional harm to self or others.

(B) There is clinically significant personal distress or impairment in social, work, or other important areas associated with the frequency and intensity of these sexual fantasies, impulses, or behaviours.

(C) These sexual fantasies, impulses, or behaviours are not a direct result of medical conditions (e.g., brain tumours or dementia) or substance intake (e.g., a substance of abuse or medication).

In contrast, the DSM-5-TR, from the American Psychiatric Association, does not include hypersexuality as a distinct diagnostic category. Instead, it acknowledges compulsive sexual behavior as a potential symptom or feature that can manifest in other conditions, such as behavioral addictions or impulse control disorders. This difference highlights the ongoing discussion about whether hypersexuality should be considered a standalone disorder or a symptom of other underlying issues.

Despite these differences, both classifications acknowledge the distress and functional impairment associated with hypersexual behaviors, emphasizing the clinical relevance of addressing this issue.

Is Hypersexuality a Clinical Condition or Maladaptive Behavior?

A central question in understanding hypersexuality is whether it constitutes a distinct clinical condition or should be viewed as a maladaptive behavior stemming from other underlying issues. While the debate continues, the prevailing view leans towards recognizing hypersexuality as a potentially clinically relevant condition, often secondary to other factors.

Defining hypersexuality as “a psychological and behavioural alteration as a result of which people seek sexually motivated stimuli in inappropriate ways, often in a manner that is not completely satisfactory” underscores its nature as a deviation from typical sexual behavior that causes distress or dysfunction. This definition allows for hypersexuality to be considered a clinically relevant condition, resulting from maladaptive behaviors that deviate from the statistical norm.

The secondary nature of hypersexuality is supported by various etiological hypotheses that link it to underlying neurological, psychiatric, or psychological factors. These factors can be broadly categorized as:

Neurological Syndromes

Several neurological conditions have been associated with hypersexuality, suggesting a biological basis in some cases. These include:

- Klüver-Bucy syndrome: Characterized by bilateral lesions of the amygdala, this syndrome can lead to disinhibited behaviors, including hypersexuality.

- Dementias: Both typical and atypical dementias, particularly those affecting the temporofrontal lobes, can result in changes in sexual behavior, including hypersexuality. Pick’s dementia is one example.

- Kleine-Levin syndrome: Also known as recurrent hypersomnia, this rare neurological disorder can manifest with hypersexuality during episodes.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): While not always present, hypersexuality can occur in some individuals with ASD.

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Studies have shown a correlation between ADHD and hypersexuality, potentially due to impulsivity and difficulties with regulation.

Psychiatric Forms

Hypersexuality is frequently observed in conjunction with various psychiatric disorders, indicating a potential comorbidity or symptomatic relationship. These include:

- Bipolar disorder: Particularly during manic or hypomanic phases, individuals may experience increased libido, impulsivity, and hypersexual behaviors.

- Borderline personality disorder (BPD): Impulsivity and risky behaviors, including hypersexuality, are common features of BPD.

- Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): While debated, some theories propose a link between hypersexuality and OCD, particularly in the realm of compulsive behaviors.

- Behavioral addictions: Hypersexuality can be considered a behavioral addiction in itself, or co-occur with other addictive behaviors.

- Personality disorders: Certain personality disorders, such as narcissistic personality disorder (covert type), histrionic, and antisocial personality disorders, have been linked to hypersexual traits.

Encephalon Trauma

Traumatic brain injuries, especially those affecting the temporofrontal regions and limbic system responsible for rationality and impulse control, can sometimes lead to the development of hypersexuality. Damage to these areas can disrupt normal sexual behavior regulation.

Drug-Induced Hypersexuality

Certain substances, both illicit and prescription, can induce or exacerbate hypersexual behaviors. These include:

- Excitatory drugs: Stimulants like methamphetamine, cocaine, synthetic drugs, and hallucinogens can increase libido and disinhibition, leading to hypersexuality.

- Dopaminergic medications: Drugs like L-dopa and prolactin inhibitors, used to treat Parkinson’s disease, have been associated with hypersexuality due to their impact on dopamine pathways in the brain.

- Anabolic steroids and sex hormones: Testosterone and other sex hormone products can increase sexual drive and potentially contribute to hypersexuality in susceptible individuals.

Understanding these potential underlying factors is crucial for a comprehensive approach to diagnosing and treating hypersexuality, moving beyond simply labeling the behavior and addressing potential root causes.

Etiopathological Theories of Hypersexuality: Unpacking the Causes

While the exact causes of hypersexuality remain under investigation, several etiological theories attempt to explain its development. These theories offer different perspectives, often overlapping and contributing to a multifaceted understanding of the condition.

Compulsive Model

This model proposes that hypersexuality is a form of obsessive-compulsive behavior. Sexual fantasies become obsessions – intrusive and recurrent thoughts – while sexual behaviors act as compulsions, performed to reduce anxiety or distress associated with these obsessions. However, a key distinction is that in hypersexuality, these thoughts and behaviors may be perceived as egosyntonic, meaning they are consistent with the individual’s self-image and desires, unlike the ego-dystonic nature of typical OCD obsessions which are unwanted and distressing. This distinction challenges a direct classification of hypersexuality within the strict category of obsessive-compulsive disorders.

Impulsive Model

The impulsive model, favored by the World Health Organization in its ICD-11 classification, views hypersexuality as an impulse control disorder. This perspective emphasizes the individual’s inability to manage sexual impulses, acting on them without adequate modulation or consideration of consequences. The model suggests a deficiency in frontal lobe function, leading to a lack of inhibition and difficulty delaying gratification of sexual urges. However, critics point out that hypersexual behavior is often not purely impulsive but can involve planning and methodical execution, suggesting a more complex interplay than simple impulsivity.

Neurobiological/Addiction Model

The addiction model frames hypersexuality as a behavioral addiction, drawing parallels with substance use disorders. This model highlights several shared characteristics:

- Tolerance: The need to escalate sexual activity to achieve the same level of satisfaction.

- Withdrawal: Experiencing negative symptoms like anxiety, rumination, and guilt when sexual activity is absent.

- Loss of control: Difficulty reducing or controlling sexual behaviors despite negative consequences.

- Preoccupation: Spending excessive time seeking sexual partners and engaging in sexual activities.

- Negative consequences: Continuing sexual behavior despite adverse impacts on personal and social life.

Neuroscientific research supports this model, revealing dysregulation in dopamine and serotonin systems, neurotransmitter pathways implicated in addiction. Studies using neuroimaging have shown dysfunction in these systems in individuals with hypersexuality, particularly in brain regions associated with reward and motivation, such as the nucleus accumbens. Dopamine dysregulation, specifically in the mesolimbic-dopaminergic and nigrostriatal pathways, is hypothesized to contribute to the compulsive pursuit of sexual satisfaction. Serotonin and oxytocin are also being investigated for their potential roles in hypersexuality, although research is ongoing.

Psychotraumatic Model

This model emphasizes the role of trauma in the development of hypersexuality. It suggests that hypersexual behavior can be a maladaptive coping mechanism in response to past traumatic experiences, particularly childhood trauma. Psychometric assessments often reveal a higher prevalence of childhood trauma in individuals with hypersexuality, supporting this theory. Trauma can disrupt healthy sexual development and emotional regulation, potentially leading to dysfunctional sexual behaviors as a way to manage distress or seek comfort.

These etiological models, while distinct, are not mutually exclusive and likely interact in complex ways to contribute to the development of hypersexuality. A comprehensive understanding requires considering biological, psychological, and social factors, including individual vulnerabilities and life experiences.

The Perrotta Hypersexuality Global Spectrum of Gradation (PH-GSS): A Proposed Framework

Recognizing the lack of clear differentiation within the broad term “hypersexuality,” the original article proposes the Perrotta Hypersexuality Global Spectrum of Gradation (PH-GSS) as a tool to classify and grade hypersexual behaviors based on their functional impact. This scale aims to move beyond a binary view of “hypersexual” versus “not hypersexual,” offering a nuanced spectrum that distinguishes between different levels of severity and functional impairment.

The PH-GSS categorizes hypersexuality into two main groups: High-Functioning Pathological and Pathological Attenuated/Corrupt Functioning. Each category is further divided into levels with associated colors and behavioral descriptions:

High-Functioning Pathological

- Level 1 (Pink): Pro-active hypersexuality: Increased sexual drive above the statistical average, but within physiological/subjective normality. Behavior is moderated, socially adaptable, with no dysfunctional conduct or significant paraphilias. Driven to seek sexual fulfillment, but behavior remains within acceptable boundaries.

- Level 2 (Yellow): Dynamic hypersexuality: Marked increase in sexual drive, still within physiological/subjective normality. Moderates behavior, adapts socially, but with stronger drive. Increased pursuit of sexual fulfillment. Mild dysfunctional behaviors or paraphilias may be present, but no extreme impulsivity.

Pathological Attenuated Functioning

- Level 3 (Orange): Dysfunctional hypersexuality: Significantly increased sexual drive, no longer within physiological/subjective normality. Difficulty moderating behavior, coarse social adaptation due to strong drive. Excessive pursuit of sexual fulfillment, dysfunctional conduct, moderate paraphilias, and impulsive acts out of context.

- Level 4 (Red): Pathological hypersexuality (grade I): Disproportionate increase in sexual drive, outside physiological/subjective normality. Poor behavior moderation, out-of-context social adaptation due to very strong drive. Extreme pursuit of sexual fulfillment, dysfunctional behaviors, serious paraphilias, impulsive acts. Aware of actions (ego-dystonic) and potential negative consequences, but emotionally detached.

Pathological to Corrupt Functioning

- Level 5 (Purple): Pathological hypersexuality (grade II): Disproportionate and unreasonable increase in sexual drive, far outside physiological/subjective normality. Unable to moderate behavior, severely compromised social adaptation. Puts self and others at risk, disregards consequences, exhibits reckless, promiscuous, impulsive, and instinctive conduct. Uncontrollable pursuit of sexual fulfillment, severe dysfunctional conduct, extreme paraphilias, irrational acts. Unaware of actions (ego-syntonic) and emotional disconnect.

This spectrum provides a more detailed and clinically relevant framework for understanding and classifying hypersexuality, moving beyond simplistic definitions and allowing for a more nuanced assessment of individual cases.

Implications for Diagnosis and Clinical Practice

The PH-GSS and the broader understanding of hypersexuality as a complex, multifaceted condition have significant implications for clinical practice. A systematic approach to diagnosing and treating hypersexuality requires:

- Comprehensive Assessment: Moving beyond simply identifying hypersexual behaviors to understanding the underlying causes, co-occurring conditions, and functional impact on the individual’s life. This includes exploring neurological, psychiatric, psychological, and traumatic factors.

- Differential Diagnosis: Distinguishing hypersexuality from normal variations in sexual desire, and differentiating it from other conditions with similar symptoms, such as bipolar disorder or personality disorders.

- Graded Approach to Treatment: Recognizing the spectrum of hypersexuality and tailoring treatment interventions to the individual’s specific level of severity and functional impairment as outlined in frameworks like the PH-GSS.

- Multidisciplinary Interventions: Employing a combination of therapies, including psychotherapy (cognitive-behavioral, constructivist-strategic), and potentially psychopharmacological interventions (anxiolytics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, antipsychotics) based on the individual’s needs and symptom profile.

- Focus on Functional Improvement: Treatment goals should extend beyond simply reducing sexual behaviors to improving overall functioning, emotional well-being, and quality of life.

By adopting a more nuanced and comprehensive approach to hypersexuality, clinicians can provide more effective and personalized care, moving towards a greater understanding and improved outcomes for individuals struggling with this challenging condition. Future research is crucial to further refine diagnostic criteria, explore the neurobiological underpinnings, and develop evidence-based treatments for hypersexuality across its spectrum of presentations.

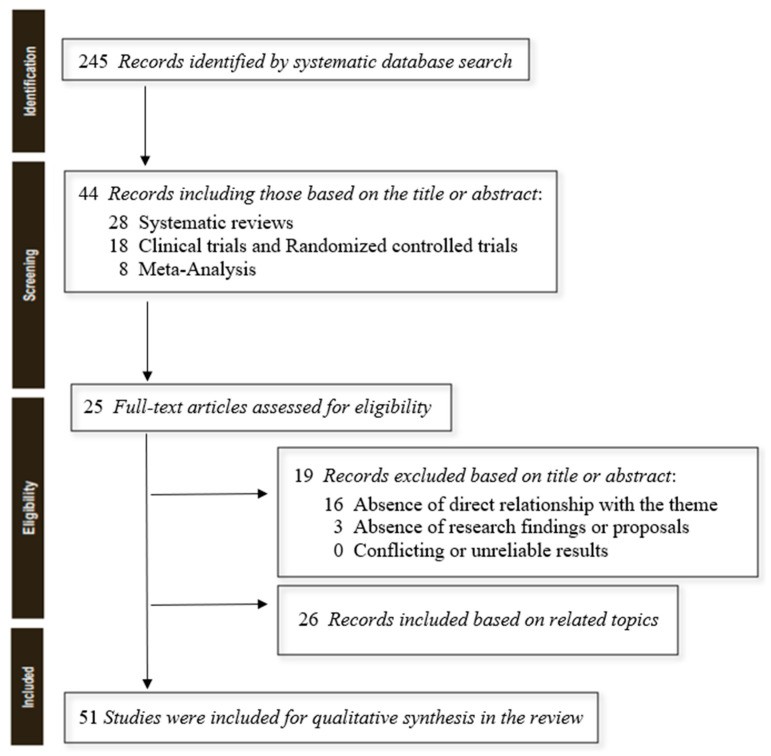

PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the systematic review process for hypersexuality research, detailing the stages of identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion of studies.