Metadata, often described as “data about data,” plays a crucial role in organizing, understanding, and managing information. It provides structured reference points that help categorize and identify attributes of the data it describes. Think of it as the DNA and the universe of data, as elegantly stated by John W. Warren in Zen and the Art of Metadata Maintenance.

The prefix “meta” generally signifies an underlying description. Metadata summarizes essential details about data, facilitating the easy discovery, utilization, and reuse of specific data instances.

For instance, basic metadata for a document file includes elements like author, creation date, modification date, and file size. The ability to search using these metadata elements makes locating a specific document considerably simpler.

Beyond document files, metadata is extensively employed for:

- Computer files

- Images

- Relational databases

- Spreadsheets

- Videos

- Audio files

- Web pages

Its importance is especially pronounced on web pages, where metadata provides descriptions of the page’s content and relevant keywords. Search engines often display this information in search results, directly influencing a user’s decision to visit a particular site. This is often implemented using meta tags.

Meta Tags and SEO: A Historical Perspective

Meta tags play a crucial role in helping search engines understand the relevance of a web page. Initially, they were a primary factor in determining search engine rankings up until the late 1990s. However, the rise of search engine optimization (SEO) led to widespread keyword stuffing in metadata, where websites excessively used keywords to manipulate search engine results.

Consequently, search engines reduced their reliance on meta tags, although they still consider them during page indexing. Search engines frequently update their ranking algorithms, like Google known for its frequent algorithm changes, to combat manipulative SEO tactics. This ensures that search results remain relevant and useful for users.

Manual vs. Automated Metadata Creation

Metadata can be created through two main methods: manually and automatically. Manual creation allows for greater accuracy, as users can input specific details and insights relevant to the data. Automated metadata creation, on the other hand, is more basic, typically capturing file size, extension, creation date, and creator information.

Metadata Use Cases: Enhancing Data Utility

Metadata is generated whenever a data asset is created, modified, or even deleted. Accurate metadata extends the lifespan of existing data by enabling users to find new applications and insights.

Metadata organizes data objects by associating relevant terms, enabling the identification and pairing of dissimilar objects to optimize data asset usage. Web browsers and search engines interpret metadata tags associated with HTML documents to determine which web content to display.

The language used in metadata is designed to be understandable by both computer systems and humans, promoting better interoperability and integration between different applications and systems.

Industries such as digital publishing, engineering, financial services, healthcare, and manufacturing leverage metadata to improve products and upgrade processes. For example, streaming content providers use metadata to manage intellectual property, protecting copyright holders while making content accessible to authenticated users.

The increasing maturity of AI technologies is also simplifying metadata management by automating previously manual tasks, such as cataloging and tagging information assets. This automation helps streamline data governance and improve data quality.

A Brief History of Metadata

While Jack E. Myers claimed to have coined the term “metadata” in 1969, references to the concept appeared in academic papers dating back to the 1960s.

David Griffel and Stuart McIntosh described metadata in a 1967 academic paper as “a record… of the data records” resulting from gathering bibliographic data from discrete sources. They suggested a “meta-linguistic approach” to enable computer systems to properly interpret this data.

In 1964, Philip R. Bagley explored the idea of associating data elements to related “metadata elements” in his dissertation. Although his thesis was rejected, Bagley’s work was later published as a report under a contract with the U.S. Air Force Office of Scientific Research in 1969.

Types of Metadata and Practical Examples

Metadata is categorized based on its function in information management. The most common types include:

- Administrative Metadata: Governs data access, user permissions, and maintenance. It includes details like creation date, file size, type, and archiving requirements.

- Descriptive Metadata: Identifies specific characteristics of data, such as bibliographic data, keywords, song titles, and volume numbers.

- Legal Metadata: Provides information on creative licensing, copyrights, and royalties.

- Preservation Metadata: Guides data placement within a hierarchical framework.

- Process Metadata: Outlines procedures used to collect and treat statistical data, also known as statistical metadata.

- Provenance Metadata: Tracks the history of data as it moves throughout an organization, ensuring data validity and correcting errors. This is also known as data lineage.

- Reference Metadata: Relates to information describing the quality of statistical content.

- Statistical Metadata: Describes data that helps users interpret and use statistics in reports and surveys.

- Structural Metadata: Reveals how different elements of a compound data object are assembled. For example, organizing pages in an audiobook to form chapters.

- Use Metadata: Data that is sorted and analyzed each time a user accesses it, providing insights into customer behavior and enabling businesses to adapt their products and services.

Effective Use of Metadata: Maximizing Business Value

The rapid growth of data has increased interest in the potential business value of metadata. Various data structures present both opportunities and challenges.

Metadata management provides an organizational framework to harmonize discrete data sets stored across various systems, and to establish a consensus on describing information. It is often broken down into business, operational, and technical data.

Companies implement metadata management to eliminate older data and develop a taxonomy to classify data according to its business value. A central database, or data dictionary, serves as a metadata repository.

Metadata management strategies also improve data analytics, develop data governance policies, and establish audit trails for regulatory compliance. At its core, it enables users to identify the attributes of a particular piece of data through a web-based user interface, understanding the data’s origins and its role within the enterprise system.

Standardization of Metadata: Ensuring Consistency

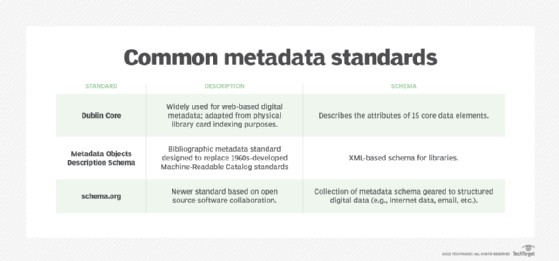

Industry standards have been developed to enhance the utility of metadata, ensuring consistency in language, format, and other attributes. Each standard is based on a specific schema that provides an overarching structure for all its metadata.

Dublin Core is a widely used general standard originally developed to aid in indexing physical library card catalogs. It describes 15 core data elements: title, creator, subject, description, publisher, contributors, date, type, format, identifier, source, language, relation, coverage, and rights management.

Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) is a similar XML-based schema for libraries, created by the U.S. Library of Congress.

Schema.org is a newer standard based on open-source software collaboration, providing a collection of metadata schema geared to structured internet data, email, and other forms of digital data.

Industry-Specific Metadata Schema

Several standard metadata schemas have been developed to meet the unique requirements of various disciplines and industries:

- Arts and humanities

- Culture and society

- Sciences

In conclusion, metadata is essential for effective data management, providing the context and structure needed to unlock the full potential of information assets. Its use is only set to grow in importance as organizations deal with ever-increasing volumes of data.