Osmosis is a fundamental concept in biology, crucial for understanding how cells function and interact with their environment. You’ll often encounter the definition of osmosis in textbooks as follows:

In biology, osmosis is defined as the net movement of water molecules across a semi-permeable membrane from an area of higher water concentration (a dilute solution) to an area of lower water concentration (a concentrated solution). This movement occurs down a water concentration gradient.

To fully grasp this definition, let’s break down the key components:

- Water Molecules: Osmosis specifically refers to the movement of water, the most abundant molecule in living organisms.

- Semi-permeable Membrane: Also known as a partially permeable membrane, this acts as a selective barrier. It allows some molecules, like water, to pass through, but restricts the passage of larger molecules, such as sugars and salts. Cell membranes in biological systems are excellent examples of semi-permeable membranes.

- Concentration Gradient: This refers to the difference in concentration of a substance across a space. In osmosis, we focus on the water concentration gradient. Water moves from where it is more concentrated to where it is less concentrated, attempting to equalize the concentration on both sides of the membrane.

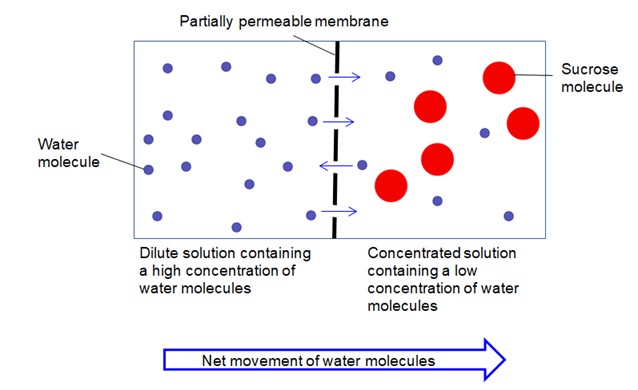

Diagram illustrating osmosis: water molecules move from a high concentration (dilute solution) to a low concentration (concentrated solution) across a partially permeable membrane.

Diagram illustrating osmosis: water molecules move from a high concentration (dilute solution) to a low concentration (concentrated solution) across a partially permeable membrane.

Let’s consider the diagram above to visualize this process. On the left side of the partially permeable membrane, we have a dilute solution, representing a high concentration of water molecules (shown as blue circles). On the right side, there is a concentrated solution, indicating a lower concentration of water molecules along with larger solute molecules (red circles).

Due to the higher concentration of water molecules on the left, there’s a greater probability of water molecules colliding with and passing through the membrane from left to right. Conversely, fewer water molecules from the right side are likely to collide and pass through to the left because of the lower water concentration.

This difference in movement results in a net flow of water molecules from the dilute solution to the concentrated solution – from left to right in this diagram. It’s crucial to understand that water molecules are constantly moving in both directions across the membrane, but the net movement is directed towards the area of lower water concentration. This movement continues until the water concentration reaches equilibrium on both sides of the membrane, although in biological systems, other factors often prevent true equilibrium from being reached.

This movement “down the concentration gradient” is a key characteristic of osmosis. Water is essentially moving from an area where it is more abundant to an area where it is less abundant, in terms of concentration.

Osmosis in Plant Cells: Turgor and Flaccidity

Osmosis plays a vital role in plant cells, particularly in maintaining their turgidity and overall structure.

-

Turgid Cells: If a plant cell is surrounded by a hypotonic solution (a solution with a higher water concentration than inside the cell), water will move into the cell via osmosis. This influx of water causes the cell to swell and become firm, or turgid. The pressure exerted by the cell contents against the cell wall is known as turgor pressure. Turgor pressure is essential for plant rigidity, helping stems and leaves stay upright and preventing wilting.

-

Flaccid Cells: Conversely, if a plant cell is placed in a hypertonic solution (a solution with a lower water concentration than inside the cell), water will move out of the cell by osmosis. This water loss causes the cell to shrink and become flaccid or soft. Reduced turgor pressure in plant cells leads to wilting, as the structural support provided by turgidity is lost.

-

Isotonic Solution: In an isotonic solution, the water concentration outside the cell is equal to the water concentration inside the cell. In this scenario, there is no net movement of water, and the cell remains in a normal, albeit not maximally turgid, state. Water molecules still move across the membrane in both directions, but the rates are balanced.

Osmosis and Transpiration: Water Transport in Plants

Osmosis is also intrinsically linked to transpiration, the process by which water is transported throughout plants. Water absorption in plant roots begins with osmosis. Root hair cells, with a higher solute concentration than the surrounding soil water, facilitate water movement from the soil into the root cells via osmosis.

Once inside the root cells, water moves into the xylem vessels, specialized tubes that transport water up the plant. Water molecules exhibit cohesion, meaning they are attracted to each other due to hydrogen bonds. As water evaporates from the leaves through stomata (tiny pores), it creates a tension that pulls water upwards through the xylem from the roots. This continuous column of water is maintained by cohesion and driven by the transpiration pull, with osmosis playing the crucial initial role in water uptake from the soil.

In summary, osmosis is a critical passive transport mechanism that governs water movement across semi-permeable membranes in biological systems. Understanding osmosis is key to comprehending cell biology, plant physiology, and numerous other biological processes.