The Magna Carta, also known as the “Great Charter,” stands as a cornerstone of English and Anglo-American legal history. Sealed in 1215, this historic document, originally drafted at Runnymede, became a symbol of liberty and justice, significantly shaping the development of constitutional law. Signed by King John of England under immense pressure from rebellious barons, the Magna Carta declared that even the king was subject to the law of the land, establishing fundamental principles of rights and freedoms for “free men.” This charter laid a crucial foundation for individual rights and the concept of due process in jurisprudence, resonating through centuries and influencing legal systems worldwide.

Defining the Magna Carta: A Charter of Liberties

At its heart, the Magna Carta was a charter of liberties—a written proclamation of rights and privileges. It was not initially conceived as a broad declaration of universal human rights, but rather as a pragmatic agreement to resolve a specific political crisis in 13th-century England. The “Great Charter” moniker itself, adopted later, reflects its perceived importance and impact over time. Originally, it was more accurately understood as a peace treaty between King John and a group of powerful barons who had risen in revolt against his oppressive rule. These barons sought to limit the king’s power and protect their own rights and properties. However, the significance of the Magna Carta quickly transcended its immediate context.

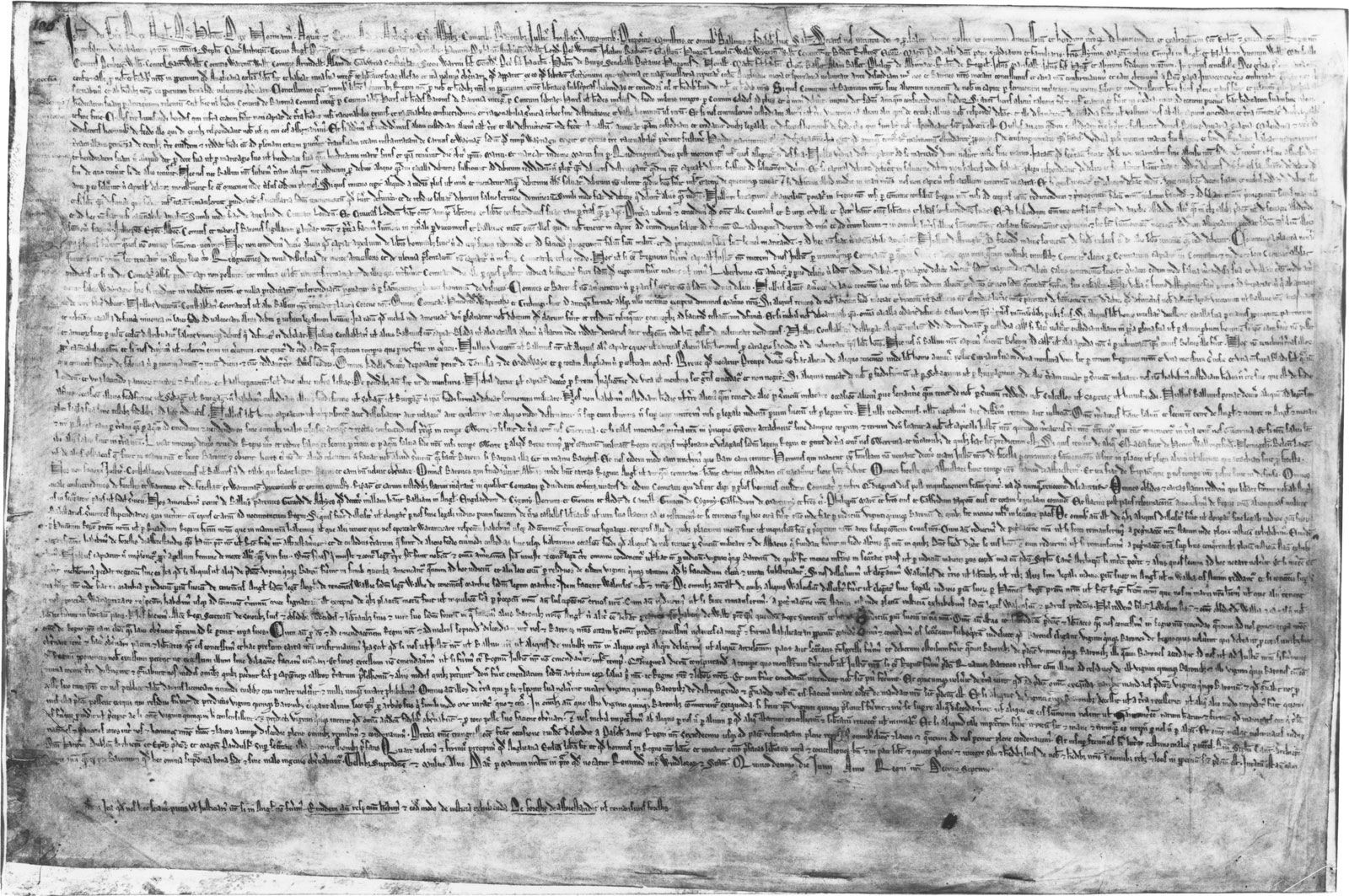

The opening of the preamble to the Magna Carta of 1215, housed in the British Library, showcasing the historical script and significance of the document.

The Historical Context: Seeds of Rebellion Against King John

The genesis of the Magna Carta is deeply rooted in the tumultuous reign of King John (1199-1216). Following the Norman Conquest of 1066, English monarchs had amassed considerable power. While earlier kings like Henry I had issued charters of liberties upon their coronation as symbolic gestures, these were often vague and inconsistently enforced. By the late 12th and early 13th centuries, the English baronage felt increasingly vulnerable to the arbitrary actions of the crown.

King John’s rule exacerbated these tensions. His military failures, particularly the loss of Normandy to France in 1204, diminished his prestige and increased his reliance on English resources. To finance his wars and compensate for lost territories, John imposed heavy taxes and scutage (payments in lieu of military service) on the barons. These financial demands, coupled with John’s perceived tyrannical behavior and disregard for established customs, fueled widespread discontent among the nobility.

Further compounding the crisis was John’s conflict with the Church. His dispute with Pope Innocent III over the appointment of Stephen Langton as Archbishop of Canterbury led to a papal interdict (1208-1213) and John’s excommunication in 1209. This conflict alienated the powerful English Church and further weakened John’s authority. Archbishop Langton, once installed, played a pivotal role in the baronial rebellion, advising the barons to base their demands for liberties on the coronation charter of Henry I, providing a historical precedent for limiting royal power.

King John of England, whose reign and policies directly led to the creation and signing of the Magna Carta in 1215.

Key Provisions of the Magna Carta: Limiting Royal Power

The Magna Carta of 1215 contained 63 clauses addressing a range of grievances and seeking to reform various aspects of royal governance. While many clauses dealt with specific feudal issues relevant to the 13th century, several provisions have had a lasting impact on the development of legal and constitutional principles.

Among the key provisions were clauses guaranteeing the “freedom of the English Church,” reforming law and justice, and regulating the conduct of royal officials. Significantly, Clause 39, one of the most famous clauses, declared that no “free man” should be seized, imprisoned, or deprived of his rights or possessions except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land. This clause is widely interpreted as a precursor to the concept of due process and trial by jury.

Clause 40 further reinforced the principles of justice, stating, “To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.” This commitment to accessible and impartial justice became a cornerstone of the English legal system.

Another noteworthy clause, Clause 61, known as the “security clause,” authorized the barons to elect 25 of their members to act as a form of oversight, ensuring the king adhered to the charter’s provisions. While this clause was controversial and later omitted in reissues, it reflected the barons’ determination to enforce the charter and hold the king accountable.

An engraving depicting King John signing the Magna Carta at Runnymede on June 15, 1215, marking a pivotal moment in legal history.

Reissues and Evolution: From Feudal Document to Universal Symbol

The Magna Carta of 1215 was short-lived in its initial form. King John quickly sought to have it annulled by Pope Innocent III, and civil war erupted shortly after its sealing. However, the principles enshrined in the Magna Carta proved remarkably resilient.

Following John’s death in 1216, his successor, the young King Henry III, reissued the Magna Carta in 1216, 1217, and again in 1225. These reissues, while containing some modifications and omissions (including Clause 61), helped to solidify the charter’s place in English law. The 1225 version, in particular, became the definitive text of the Magna Carta.

Over time, the interpretation of the Magna Carta broadened. While initially intended to protect the rights of the baronage, it came to be seen as a guarantee of liberties for all “free men,” and eventually, for all English subjects. Legal scholars and parliamentarians reinterpreted its clauses in light of contemporary concerns, finding in it justifications for principles such as habeas corpus, parliamentary sovereignty, and limitations on executive power.

The Enduring Legacy of Magna Carta: A Foundation for Modern Rights

The Magna Carta’s enduring influence extends far beyond its medieval origins. It has become a potent symbol of constitutionalism, the rule of law, and individual liberty across the globe. It is considered a foundational document for common law legal systems and has profoundly influenced the development of democratic institutions and human rights declarations worldwide.

The principles embedded in the Magna Carta, particularly the concepts of due process and the limitation of arbitrary power, were instrumental in shaping the development of Parliament in England. Later, English colonists carried these principles to North America, where they profoundly influenced the American Revolution and the formation of the United States. The Magna Carta is directly cited or reflected in foundational American documents such as the Declaration of Independence, the U.S. Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

Even today, the Magna Carta continues to resonate as a powerful testament to the idea that no one, not even the highest ruler, is above the law. Its legacy serves as a constant reminder of the importance of safeguarding fundamental rights and liberties against tyranny and oppression, making it a truly indispensable document in the history of freedom and justice.

An early 14th-century illumination of King John of England, highlighting his historical significance in relation to the Magna Carta.