Introduction

In the realm of public health and individual well-being, health literacy has emerged as a critical determinant of health outcomes in modern society. Originating as a concept in the 1970s [1], health literacy broadly addresses an individual’s competence in navigating the complexities of health promotion and maintenance [2]. Over the past two decades, this concept has garnered increasing attention due to its profound implications for individual and public health, as well as the sustainability of healthcare systems [3–8]. Its importance is particularly amplified in an era dominated by non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and escalating healthcare costs [9], underscoring the necessity for individuals to proactively manage their health and engage more effectively with health services [10].

The consequences of inadequate health literacy are far-reaching, contributing to difficulties in comprehending health information, limited disease knowledge, and reduced medication adherence. These factors collectively lead to poorer health, elevated mortality risks, inefficient healthcare utilization, increased healthcare expenditures, and pronounced health disparities [4 6 11]. Current evidence strongly suggests that bolstering health literacy stands as one of the most promising and cost-effective strategies to confront the challenges posed by NCDs [12 13]. Recognizing its significance, numerous nations, including the USA, Canada, Australia, the European Union, and China, have prioritized health literacy within their health policies and practices [14]. The World Health Organization (WHO) also champions health literacy as a vital instrument for achieving key targets outlined in the Sustainable Development Goals [15].

Despite the widespread acknowledgment of health literacy’s importance and extensive research in this area, a fundamental question persists: What Is The Meaning Of health literacy? A definitive consensus on its conceptual underpinnings remains elusive [16]. This lack of clarity is not merely an academic debate; it has practical ramifications. The concept’s flexibility, while seemingly accommodating, has led to a proliferation of over 250 definitions in academic literature [17], making it challenging to pinpoint its precise meaning. This ambiguity hinders the development of robust and reliable measurement tools, impedes accurate evaluation and comparison of health literacy interventions, and complicates the synthesis of evidence to inform effective improvement strategies [13 14 16–18]. Furthermore, conceptual confusion can breed disjointed and even contradictory research findings, potentially undermining the development and implementation of trustworthy and effective health literacy-related policies and interventions [13 14 16].

To address this critical gap in understanding, this study undertakes a systematic review and qualitative synthesis of existing research across diverse contexts to clarify what health literacy truly represents. By examining the various interpretations and conceptualizations of health literacy, this review aims to provide a more robust and nuanced understanding of this vital concept for researchers, practitioners, and policymakers alike.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This systematic review, registered under protocol number CRD42017065149, adhered to the ENTREQ (Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative research) guidelines to ensure rigor and transparency. The search strategy was adapted from a previous systematic review [5], employing a combination of keywords such as ‘health literacy’, ‘definition’, and ‘concept’ to comprehensively capture relevant literature. Databases searched included PubMed, Medline, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, PsycARTICLES, and the Cochrane Library, with a publication date range from January 1, 2010, to March 15, 2017 (the date of the last search). This timeframe was chosen because the most recent systematic review at the time analyzed literature published before 2010 (search protocol details are available in online supplementary table S3).

Supplementary data fmch-2020-000351supp001.pdf is available for download (183.3KB, pdf)

Two independent reviewers assessed titles, abstracts, and full texts of retrieved records against predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through consultation with a third author to ensure consistency and objectivity in the selection process.

Studies were included if they explicitly aimed to define health literacy or offered implicit contributions to understanding its concept, such as explorations of health literacy constructs. Studies were excluded if they were interpretive in nature, utilizing existing conceptual frameworks without further conceptual contribution, lacked theoretical presentation of health literacy, or were not written in English.

To further broaden the search, references of included articles were also scrutinized to identify additional relevant studies, including those published before 2010 that may have been missed in previous systematic reviews [5, 19].

Data Analysis

A structured data collection chart (online supplementary table S4) was developed to guide the extraction of bibliographic information and findings related to the conceptualization of health literacy from the included studies. Bibliographic data included study objectives, methods, setting, participants, data collection, and analysis methods. Data related to conceptualization focused on the underlying constructs and meaning of health literacy [5, 19]. Data extraction was performed independently by two authors, and the extracted data sets were cross-checked and synthesized through group discussions to ensure accuracy and completeness.

A data-driven thematic analysis, utilizing a semigrammatical coding approach [20], was employed. Following Braun and Clarke’s [21] four-step framework, the analysis progressed through: data familiarization, initial coding, theme searching, and theme reviewing and naming.

In the initial data familiarization phase, included studies were thoroughly read, and all statements pertinent to the research question—what is the meaning of health literacy—were identified and recorded using the data collection chart, forming a comprehensive data pool for qualitative synthesis. This process yielded a total of 570 relevant statements.

The second phase, initial coding, involved dividing each statement into components using a semigrammatical approach. These components included ‘cores’, ‘actions’, ‘objects’, ‘aims’, and ‘others’ (such as context). For example, Freedman et al.‘s [22] definition of health literacy as ‘the skills necessary to obtain, process, evaluate, and act upon information needed to make public health decisions that benefit the community’ was coded as: ‘necessary skills’ (cores), ‘to obtain, process, evaluate and act upon’ (actions), ‘needed information’ (objects), and ‘to make public health decisions that benefit the community’ (aims).

The third phase, theme searching, focused on extracting shared common themes across the coded statements. The clustering of codes into themes was primarily based on the ‘cores’ codes (n=74), but also considered ‘actions’, ‘objects’, ‘aims’, and ‘others’ codes to ensure a holistic representation of the data.

Finally, in the theme reviewing and naming phase, extracted themes were reviewed against the initial coding and the entire data pool. Themes were refined and renamed as necessary to ensure they accurately represented the data pool and that the relationships between codes and themes were not distorted.

Steps 1 and 2 were conducted independently by two reviewers, with results cross-checked and reconciled through discussions. Steps 3 and 4 were conducted collaboratively within the research team, with consensus achieved through ongoing negotiations and discussions.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

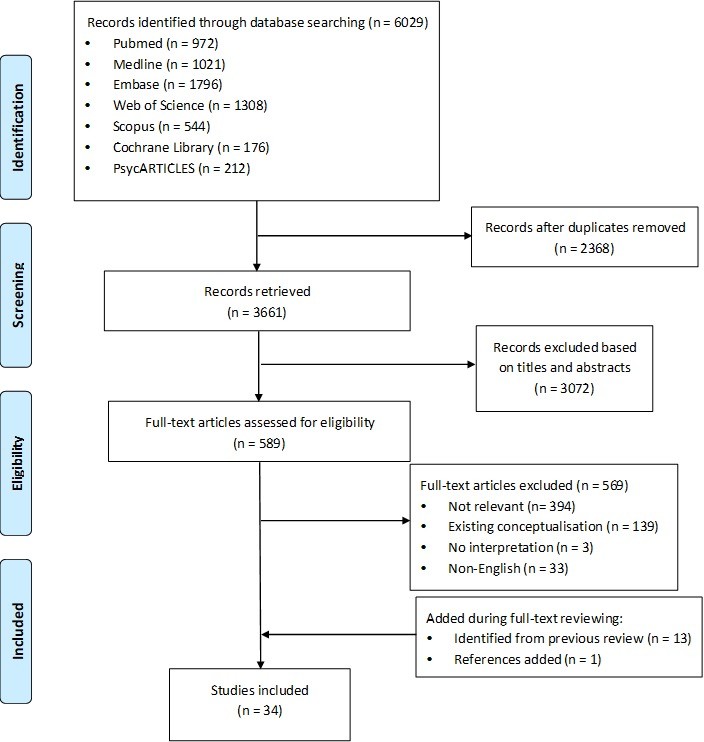

The database searches yielded 6029 records, from which 2368 duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening led to 589 studies for full-text review. Of these, 569 studies were excluded for not meeting inclusion criteria: 394 lacked conceptualization of health literacy; 139 were interpretive, focusing on existing frameworks; 3 lacked concept interpretations; and 33 were non-English publications. Thirteen studies from previous systematic reviews [5, 19] and one additional study identified through reference screening were added. The final sample for this systematic review comprised 34 studies (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the systematic review process for defining health literacy, detailing the stages of article retrieval, screening, inclusion, and final sample selection.

Flowchart illustrating the systematic review process for defining health literacy, detailing the stages of article retrieval, screening, inclusion, and final sample selection.

ENTREQ flow diagram of systematic review.

Approximately two-thirds of the included studies explored the concept of health literacy in general populations [3–5, 19, 20, 22–37], while the remainder focused on specific populations, including children and adolescents [38–42], elderly people [43], patients with chronic diseases [44–47], gay men [48], cancer caregivers [49], and individuals with limited English proficiency [50]. Most studies adopted a broad, general concept of health literacy, not limited to specific health topics. However, eight studies contextualized health literacy within particular domains, such as public health [22], sexual health [48], tobacco control [41], complementary medicine [37], verbal information exchange [35], functional health [47], and critical thinking [34, 36] (online supplementary table S1).

Of the 34 studies, 19 presented original data [4, 5, 19, 20, 23, 24, 26, 28, 32, 35–37, 39, 41–44, 48, 49], and 15 were theoretical proposals [3, 22, 25, 27, 29–31, 33, 34, 38, 40, 45–47, 50]. The former employed concept analyses [28, 32, 36, 43], concept mapping [23, 49], thematic analyses [5, 19, 24, 35, 41, 42, 48], grounded theory analyses [26, 35, 39], semigrammatical analyses [20], or framework analyses [44] on qualitative data from documents, interviews, or focus groups. The latter, theoretical studies, largely represented expert opinions with limited detail on conceptualization methods. These theoretical studies were predominantly published before 2013, during the early stages of health literacy concept development. Since then, empirical studies have become more prevalent (online supplementary table S1).

What is Health Literacy? Conceptualizations from the Literature

Across the included studies, health literacy was commonly conceptualized in three primary ways: as a set of knowledge, a set of skills, or a hierarchy of functions (functional-interactive-critical).

Health Literacy as a Set of Knowledge:

Four studies emphasized knowledge as the central element of health literacy. Schulz and Nakamoto [25] defined health literacy as encompassing basic literacy, declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, and judgment skills. Declarative knowledge refers to factual understanding about health, while procedural knowledge involves understanding the rules guiding reasoned health choices and actions. Together, these knowledge types enable individuals to acquire and utilize information in various contexts and govern competence across different tasks [25]. Similarly, Paakkari and Paakkari [38] conceptualized health literacy as theoretical knowledge, practical knowledge, and critical thinking, mirroring Schulz and Nakamoto’s declarative knowledge, procedural knowledge, and judgment skills [25]. Paakkari and Paakkari [38] further included self-awareness and citizenship as components of health literacy, representing the ability to assess oneself informedly and take responsibility for broader health improvement. Rowlands et al. [24] identified health literacy as the ability to acquire, understand, and evaluate health knowledge. Shreffler-Grant et al. [37] specified knowledge of dosage, effects, safety, and availability of medicines as health literacy in the context of complementary medicine (online supplementary table S1).

Health Literacy as a Set of Skills:

The Institute of Medicine (IoM) model is arguably one of the most influential frameworks for understanding health literacy. This model proposes four core constructs: cultural and conceptual knowledge, print health literacy (reading and writing skills), oral health literacy (listening and speaking), and numeracy [4]. It strongly emphasizes the skills needed to obtain, process, and apply health information, particularly within medical care. This model has resonated with numerous researchers. For instance, Baker [30] refined the elements of print and oral health literacy for general populations. Harrington and Valerio [35] detailed verbal health information exchange, akin to oral health literacy. Yip [50] highlighted the importance of speaking, reading, writing, listening, and numeracy for individuals with limited English proficiency. Squiers et al. [19] expanded oral health literacy to include negotiation skills, renaming it communication skills, and also introduced navigation skills as crucial in eHealth contexts. Sørensen et al. [5] synthesized the literature, identifying the skills to access, understand, appraise, and apply information and knowledge as the four core health literacy skills, encompassing the range of abilities needed to manage health information for health improvement and maintenance. Mancuso [28] and Oldfield and Dreher [43] underscored comprehension skills, while Speros [32] added successful functioning in the patient role as a core construct (online supplementary table S1).

Health Literacy as a Hierarchy of Functions:

Several studies viewed health literacy as a hierarchical construct, requiring different levels of cognitive and social skills. Nutbeam [3] initially proposed a three-level model: functional, interactive, and critical health literacy, which has been further elaborated by other researchers [34, 36, 40–42, 45, 47]. In Nutbeam’s model, functional health literacy refers to basic reading and writing skills for everyday situations. Interactive health literacy involves more advanced skills to extract information, derive meaning from communication, and apply new information to changing circumstances. Critical health literacy represents the highest level, requiring skills to critically analyze and use information to exert greater control over life events [3]. Schillinger [47] interpreted functional health literacy as basic literacy and numeracy. Chinn [34] considered critical health literacy as understanding social determinants of health and engaging in collective actions. Sykes et al. [36] expanded critical health literacy to include advanced personal skills, health knowledge, information skills, effective interactions with service providers, informed decision-making, and empowerment, including political actions. Manganello [40] added media literacy as a separate construct for adolescents, emphasizing the importance of critically assessing media messages. Liao et al. [42] examined the Nutbeam model’s meaning in children, defining functional health literacy as understanding basic health concepts and behaviors; interactive health literacy as interpersonal and communication skills; and critical health literacy as assessing and responding to health information (online supplementary table S1).

Alternative Conceptualizations:

Beyond these dominant models, some researchers offered alternative perspectives on what is the meaning of health literacy. Soellner et al. [23], based on expert views, suggested incorporating self-perception, proactive health approaches, self-regulation, and self-control. Jordan et al. [26], examining patient perspectives, proposed three dimensions: identifying health issues, engaging in information exchange, and acting on health information. Buchbinder et al. [20] combined patient and professional views, summarizing health literacy as knowledge, attitude, attribute, relationship, skills, actions, and context across 16 aspects, including diseases and health systems. Several studies highlighted population-specific elements: information consistency and delivery for gay men’s sexual health [48]; self-management skills for chronic disease patients [44]; support systems for cancer caregivers [49]; patient–provider relationships and preventive care; and adolescent rights and responsibilities [39]. Freedman et al. [22] focused on public health literacy, introducing civic orientation as skills for civic engagement in health concerns. Zarcadoolas et al. [31] included science literacy and cultural literacy as essential for interpreting and acting on health information (online supplementary table S1).

Elements of Health Literacy: Key Themes

The thematic analysis revealed three key themes that effectively represent the diverse models and perspectives on what is the meaning of health literacy found in the included studies:

- Knowledge of health, healthcare, and health systems.

- Processing and using information in various formats related to health and healthcare.

- Ability to maintain health through self-management and partnerships with health providers.

These themes provide a structured framework for understanding the multifaceted nature of health literacy and its constituent components (online supplementary table S2).

Knowledge of Health, Healthcare, and Health Systems

This theme, central to what is the meaning of health literacy, encompasses the understanding of factual health information, categorized into four aspects: knowledge of medicine, knowledge of health, knowledge of health systems, and knowledge of science [4, 20, 22, 23, 25, 31, 34, 36–39, 42–44, 49]. Knowledge of medicine refers to understanding medical contexts like medications, treatments, and illnesses. Knowledge of health focuses on everyday health information, such as healthy behaviors, lifestyles, and public health terms. Knowledge of healthcare systems involves understanding the structure and services of health systems for effective utilization. Knowledge of science includes understanding fundamental scientific concepts and arguments (online supplementary table S2).

Processing and Using Information in Various Formats in Relation to Health and Healthcare

This theme addresses the crucial question of what is the meaning of health literacy in practice, focusing on the ability to effectively process and utilize health-related information. It is further divided into four subthemes:

Ability to Process and Use Information to Guide Health Actions

This subtheme, fundamental to what is the meaning of health literacy, highlights the multidimensional skill set necessary for engaging with and applying health information. This skill set includes general literacy and numeracy skills (reading, writing, numeracy, listening, speaking) and specialized skills for obtaining, understanding, appraising, communicating, synthesizing, and applying health information. A health-literate individual knows when and where to seek health information, can comprehend its meaning, assess its credibility and relevance, share information, and express preferences. They can also compare, weigh, and integrate information for informed decision-making at individual and societal levels (online supplementary table S2).

Self-Efficacy in Processing and Using Health Information

Self-efficacy, a key element in what is the meaning of health literacy, reflects an individual’s belief in their ability to succeed in health-related tasks [20, 23, 26, 28, 36, 38, 39, 49]. This subtheme comprises self-confidence and accountability. Self-confidence involves confidently articulating oneself, questioning healthcare providers, and seeking clarification to ensure full comprehension. Accountability refers to taking responsibility for one’s health. Self-efficacy significantly influences how individuals perceive health and apply health information in their actions (online supplementary table S2).

Provision of Health Information (Active Engagement in Dissemination of Consistent Information in a Language that is Appropriate to Consumers)

Effective communication and consumer participation are vital aspects of what is the meaning of health literacy, particularly in information provision [20, 30, 39, 48, 49]. The complexity of health information can be a major barrier [30]. Consumer involvement in generating and disseminating health information is crucial to ensure simplicity, consistency, and accuracy. The approach to information provision significantly impacts individuals’ ability to understand, process, and use health information.

Access to Resources and Support for Processing and Using Information

Resources and support are essential components of what is the meaning of health literacy, facilitating the realization of individual abilities and compensating for any shortcomings in information processing [22]. This subtheme includes access to health information and infrastructure (libraries, online services), information support from healthcare providers and social networks (family, friends, community organizations), and external resources (financial resources, time) [20, 24, 36, 49] (online supplementary table S2).

Ability to Maintain Health Through Self-Management and Working in Partnerships with Health Providers

This theme, representing the ultimate goal of what is the meaning of health literacy, focuses on the ability to use knowledge and skills to manage health and illness effectively [20, 23, 28, 38, 42]. It involves both self-management and collaborative partnerships with health providers, requiring self-regulation, goal-setting, and interpersonal skills. Self-regulation encompasses self-perception, self-reflection, and self-control, enabling individuals to tailor information and apply it appropriately. Goal achievement involves setting meaningful health goals and adjusting strategies to attain them. Interpersonal skills are essential for building and maintaining harmonious relationships with others, including health providers (online supplementary table S2).

Discussion

This study synthesized 34 studies to clarify what is the meaning of health literacy. The analysis revealed that health literacy is commonly viewed as a set of knowledge, skills, or a hierarchy of functions (functional-interactive-critical). Three overarching themes emerged: (1) knowledge of health, healthcare, and health systems; (2) processing and using health information; and (3) maintaining health through self-management and partnerships.

Initially, health literacy was primarily understood as an individual’s ability to obtain health information and knowledge to guide health actions. Unsurprisingly, all included studies examined health literacy from this “information and knowledge” perspective, with a strong focus on the ability to process and utilize information for health-related decisions and behaviors.

Health literacy has frequently been defined as the ability to apply general literacy skills (reading, writing, numeracy, listening, speaking) to obtain, understand, appraise, synthesize, communicate, and apply health information. While previous reviews emphasized accessing, understanding, appraising, communicating, and applying health information as core components [5], this study highlights the foundational role of general literacy skills [4], which significantly shape how individuals access and utilize health information. For instance, strong writing skills do not automatically translate to effective verbal communication. Furthermore, “information synthesis”—the ability to compare, weigh, and integrate diverse information for informed decision-making—is a crucial skill often overlooked in previous frameworks [5, 19], especially in today’s information-rich environment.

Knowledge can be seen as both a result of information processing and a precursor to how information is used [25, 38]. Schulz and Nakamoto [25] and Paakkari and Paakkari [38] categorized knowledge into declarative/theoretical and procedural/practical knowledge. This study grouped procedural/practical knowledge under “processing and use of information,” while declarative/theoretical knowledge encompasses knowledge of medicine, health, health systems, and science.

The concept of health literacy has evolved significantly over the past decade. Concerns arose regarding the sole emphasis on “information and knowledge,” as individuals with ample knowledge may still struggle to translate it into tangible health benefits [20, 23, 26, 49]. This led to the incorporation of self-efficacy as a crucial component, reflecting confidence and willingness to utilize information for health actions. Some researchers further advocated for expanding the concept beyond individual abilities [20, 30, 48, 49]. Health knowledge is often generated by professionals, with consumers viewed as passive recipients. However, the complex language used by professionals can be challenging for consumers [48], leading to communication barriers and calls for greater consumer engagement in knowledge synthesis and dissemination.

This conceptual expansion stems from empirical investigations into what is the meaningfulness of health literacy in real-world contexts. Studies exploring diverse populations provide evidence for a broader understanding of health literacy [12, 18]. The ultimate goal of health literacy is to enable individuals to maintain health using acquired information and knowledge. This requires self-awareness, understanding one’s own situation, and collaborating with others for optimal health outcomes. Evidence from the UK suggests that patients, caregivers, and health workers perceive health literacy as a “whole system outcome” rather than solely an individual attribute [51]. Edwards et al. [52] argued that knowledge can be acquired through social networks without individual information processing. In communal settings, “group health literacy” may be even more critical than individual health literacy. Access to resources and support can serve as an indicator of this “group health literacy.”

This study significantly contributes to clarifying what is the meaning of health literacy. Pleasant [13] noted that existing definitions often lack robust scientific grounding. The widely used definition focused on individual information processing ability has not been fully supported by recent empirical research. This review proposes a revised definition, incorporating key themes identified from the literature: Health literacy is “the ability of an individual to obtain and translate knowledge and information in order to maintain and improve health in a way that is appropriate to the individual and system contexts.” This definition underscores the diverse needs of individuals and the critical interactions between consumers, healthcare providers, and healthcare systems in maintaining health. This holistic, system-oriented view is increasingly advocated by researchers and practitioners [53, 54], offering a more comprehensive understanding of health literacy and guiding future efforts to improve it.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the literature search was limited to English-language publications. Second, the quality of included publications was not formally assessed due to a general lack of detailed methodological descriptions, even in highly cited publications [3, 4, 22, 29–31, 33, 47]. While some studies provided information to support quality, such as clear recruitment strategies [26, 36, 39, 41, 42, 44, 49], detailed data collection processes [41], justifications for methodological choices [24, 36, 41, 44], and reflections on researcher roles [41, 55], more detailed methodological reporting in future health literacy research would facilitate quality assessments in subsequent syntheses. Third, the proposed definition of health literacy, while grounded in systematic review, is an initial step. Further refinement through Delphi processes and consensus conferences is recommended to develop a more robust and widely accepted definition.

Conclusions

Health literacy has been commonly conceptualized as knowledge, skills, or a hierarchy of functions. This review proposes defining health literacy as “the ability of an individual to obtain and translate knowledge and information in order to maintain and improve health in a way that is appropriate to the individual and system contexts.” This definition encapsulates the essence of the three key themes identified: (1) knowledge of health, healthcare, and health systems; (2) processing and using health information; and (3) maintaining health through self-management and partnerships with health providers. This comprehensive definition provides a clearer understanding of what is the meaning of health literacy and its multifaceted nature, paving the way for more effective research, interventions, and policies to enhance health literacy and improve health outcomes.

Footnotes

Contributors: CXL conceived the review scope with XZ and CJL. CXL, DW, and XZ conducted literature screening, review, data extraction, verification, and qualitative synthesis. CXL drafted the manuscript. All authors contributed to critical review, editing, and manuscript revision and approved the final version.

Funding: No specific grant was declared for this research.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer-reviewed.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data

fmch-2020-000351supp001.pdf is available for download (183.3KB, pdf)