What Is The Plot Of A Story? It’s the roadmap that guides readers through a narrative, a sequence of events intricately linked by cause and effect. At WHAT.EDU.VN, we understand that grasping this fundamental element is crucial for both writers and readers alike. Uncover how plot shapes character development, drives conflict, and ultimately delivers a powerful message. Dive into the essence of storytelling, narrative structure, and literary analysis with us.

1. Plot Definition: Unveiling the Core of a Story

The plot of a story represents the interconnected chain of events that form the backbone of a narrative. These events aren’t random; they are carefully linked, with each one influencing or causing the next. Story plot is fundamentally a series of cause-and-effect relationships that dictate the shape and direction of the story as a whole.

What is plot?: A series of causes-and-effects which shape the story as a whole.

Simply put, plot transcends a basic summary; it necessitates causation. Consider the words of novelist E. M. Forster:

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.” —E. M. Forster

The addition of “of grief” is the element that introduces causality, transforming a simple sequence into a plot. Without it, the Queen’s demise is ambiguous. Grief not only provides plot structure but also hints at the core theme of the story.

1.1 Essential Elements That Define a Plot

For a story to have a compelling plot, certain elements must be present:

- Causation: The bedrock of plot. Events must be linked by cause and effect, creating a chain reaction that drives the narrative forward.

- Characters: Stories revolve around individuals. The plot needs to introduce the central figures who will be impacted by the unfolding events.

- Conflict: The engine of a story. Conflict, whether internal or external, creates tension and compels characters to make choices, revealing themes and driving the narrative.

1.2 The Interplay of Elements in Plot Construction

These elements combine to shape the narrative structure of a story. Understanding these structures unlocks countless possibilities for organizing a story’s events.

Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot. —Leigh Brackett

2. Exploring Common Plot Structures in Storytelling

Throughout history, storytellers have experimented with diverse plot structures. Here’s an overview of some of the most influential frameworks that can help you overcome creative obstacles and enrich your writing:

2.1 Aristotle’s Story Triangle: The Foundation of Narrative

Aristotle’s Poetics (circa 335 B.C.) offers the earliest known exploration of plot structures. Aristotle conceptualized plot as a narrative triangle, suggesting that stories follow a linear progression with a clear beginning, middle, and end, resolving specific conflicts.

- The beginning, in Aristotle’s view, should stand independently, a self-contained unit that doesn’t rely on prior events or raise unanswered questions.

- The middle should logically build upon the beginning, expanding conflicts and exploring tragedies.

- The end should offer a clean resolution without hinting at future events.

While this basic structure provides a foundation, it can be limiting. Freytag’s Pyramid expands upon Aristotle’s concepts with greater detail.

2.2 Freytag’s Pyramid: A Five-Act Structure for Storytelling

Freytag’s Pyramid refines Aristotle’s ideas by breaking down plot into five distinct parts:

- Exposition: The story’s opening, where the main characters, settings, themes, and author’s style are introduced.

- Rising Action: Commences after the inciting incident, the event that ignites the primary conflict. This stage traces the cause-and-effect chain of events as the conflict intensifies.

- Climax: The turning point of the story, where the central conflict reaches its peak, revealing the fates of the main characters.

- Falling Action: The aftermath of the climax, as the characters grapple with the consequences and implications for their lives.

- Denouement: The story’s resolution, where loose ends are tied up. Some stories may have an open-ended denouement, leaving room for interpretation.

2.3 Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc: A Detailed Plot Blueprint

Building on Freytag’s Pyramid, Nigel Watts developed the 8 Point Arc, which identifies eight key plot points that a story should navigate:

- Stasis: The protagonist’s normal life, disrupted by the inciting incident, or “trigger.”

- Trigger: An event beyond the protagonist’s control that sets the story’s conflict into motion.

- The Quest: The protagonist’s journey to confront the story’s central conflict (akin to the rising action).

- Surprise: Unexpected events that complicate the protagonist’s journey, such as obstacles, internal flaws, or moments of confusion.

- Critical Choice: A major, life-altering decision the protagonist must make, revealing their true character and drastically altering the course of the story.

- Climax: The direct result of the protagonist’s critical choice, representing the peak of tension in the story.

- Reversal: The protagonist’s reaction to the climax, resulting in a significant shift in their status, outlook, or even their life.

- Resolution: A return to a new stasis, a transformed state emerging from the ashes of the story’s conflict and climax.

2.4 Save the Cat: A Screenwriter’s Guide to Plot Structure

Developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder, the Save the Cat structure provides a detailed framework applicable to various story types, outlining specific beats and milestones that drive the narrative.

2.5 The Hero’s Journey: A Timeless Archetype of Storytelling

The Hero’s Journey, conceived by Joseph Campbell, proposes a three-act structure that mirrors the transformative journey a hero undertakes:

- Stage 1: The Departure Act: The hero leaves their ordinary world.

- Stage 2: The Initiation Act: The hero confronts challenges and conflicts in an unfamiliar realm.

- Stage 3: The Return Act: The hero returns home, forever changed by their experiences.

Christopher Vogler expands upon this framework in The Writer’s Journey, outlining a 12-step process:

The Departure Act

- The Ordinary World: Introduction to the hero’s everyday life.

- Call to Adventure: The hero faces a challenge that compels them to leave their comfort zone.

- Refusing the Call: The hero initially resists the call due to fear or uncertainty.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero gains guidance and support from a mentor figure to prepare for the journey.

The Initiation Act

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero commits to the adventure, leaving their old world behind.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero navigates a new world, encountering challenges, forming alliances, and facing enemies.

- Approach (to the Inmost Cave): The hero prepares to confront the greatest danger, the “inmost cave.”

- Ordeal: The hero faces their biggest test, often a moment of crisis or revelation.

- Reward: The hero receives a reward for overcoming the ordeal, whether tangible or intangible.

The Return Act

- The Road Back: The hero begins the journey home, facing new dangers and challenges.

- Resurrection: The hero confronts a final, climactic challenge, demonstrating their growth and transformation.

- The Return: The hero returns home, transformed by their journey, sharing their reward or elixir with the world.

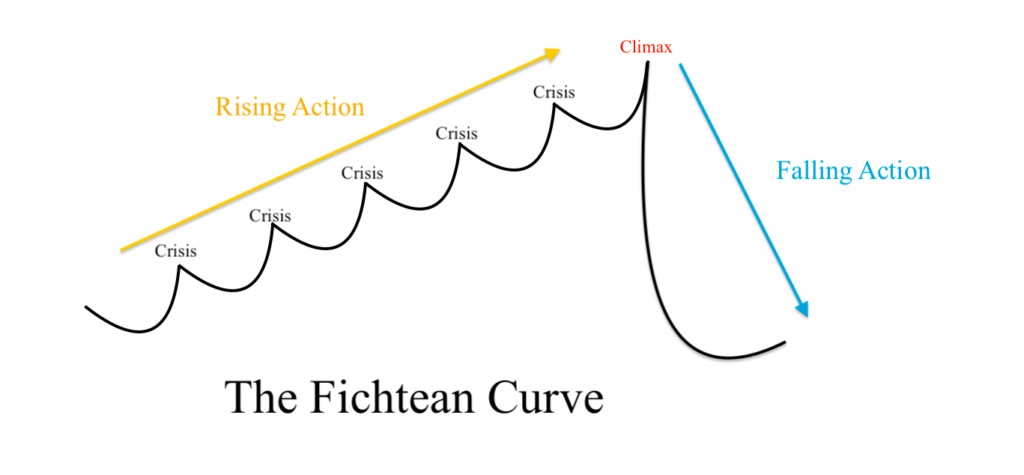

2.6 Fichtean Curve: Building Tension Through Rising Action

The Fichtean Curve, popularized by John Gardner in The Art of Fiction, emphasizes a rising action that builds tension through a series of escalating and de-escalating conflicts, culminating in a climax followed by a falling action.

3. The Role of Conflict in Driving Plot

Conflict is a core component of plot. It’s the driving force behind the inciting incident, the rising action, and ultimately, the climax and denouement.

Conflict can be:

- External: A struggle against an enemy, a system, or societal forces.

- Internal: A battle with one’s own traumas, flaws, or conflicting desires.

Without conflict, a story lacks the engine to propel it forward.

If you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict.

It’s important to recognize that the focus on conflict as a primary driver is largely a Western concept. Some storytelling traditions, like the Eastern Kishōtenketsu, emphasize character reactions to external situations rather than direct conflict resolution.

4. Common Plot Devices: Tools for Enhancing Storytelling

Plot devices are techniques that authors employ to enrich their stories, maintain reader engagement, and explore complex themes.

4.1 Aristotle’s Plot Devices

Aristotle identified three essential plot devices:

- Anagnorisis (Recognition): A moment of crucial realization where the protagonist gains vital knowledge that propels them toward resolving the central conflict.

- Pathos (Suffering): Confrontation with extreme pain, whether physical, emotional, or existential, which Aristotle argued is essential for plot development.

- Peripeteia (Reversal): A sudden shift in fortune, from good to bad or vice versa, often driven by the climax.

4.2 Plot Devices for Structuring a Story

- Backstory: Events preceding the main story that provide context, characterization, and historical parallels. Backstory can be revealed through flashbacks.

- Deus Ex Machina: A sudden, unexpected intervention that alters the protagonist’s fate, often viewed as a convenient resolution but can be effective in certain genres.

- In Media Res: Starting the story in the middle of the action, immediately grabbing the reader’s attention.

- Plot Voucher: An item or piece of information given to the protagonist early on that becomes significant later in the story.

4.3 Plot Devices for Adding Complexity and Intrigue

- Cliffhanger: Ending the story abruptly, before the climax is resolved, leaving the reader in suspense.

- MacGuffin: An object or goal that drives the plot but lacks intrinsic value.

- Red Herring: A misleading detail designed to distract the reader from the truth, common in mystery and suspense genres.

5. Eight Common Plot Types in Literature

Certain plot patterns recur throughout literature, particularly in genre fiction. These stories often rely on established tropes and archetypes:

- Quest: The protagonist embarks on a journey to find something of great value, facing challenges and transforming along the way.

- Tragedy: A well-intentioned protagonist, flawed or limited, fails to overcome the story’s conflict, often leading to personal loss or death.

- Rags to Riches: The protagonist rises from poverty to wealth, navigating issues of class, identity, and the corrupting influence of money.

- Story Within a Story: A secondary story is embedded within the main narrative, reflecting or challenging the main story’s themes.

- Parallel Plot: Two or more concurrent plots unfold simultaneously, influencing each other.

- Rebellion Against “The One”: A hero resists an oppressive, all-powerful antagonist, often facing overwhelming odds.

- Anticlimax: The story focuses on the aftermath of a climax that has already occurred, exploring the consequences and fallout.

- Voyage and Return: The protagonist journeys to a strange world, undergoes a transformative experience, and returns home changed.

6. Plot-Driven vs. Character-Driven Narratives

Stories can be broadly classified as either plot-driven or character-driven.

- Plot-driven stories prioritize the sequence of events, with characters fitting into predetermined roles and archetypes to advance the plot.

- Character-driven stories emphasize the characters’ inner lives, motivations, and choices, which shape the direction of the plot.

Literary fiction tends to be character-driven, while genre fiction often relies on plot-driven structures. However, successful stories often blend elements of both.

7. Distinguishing Plot from Story

While the terms “plot” and “story” are often used interchangeably, they have distinct meanings.

- Plot: The sequence of events in a story, answering the questions of What, When, and Where.

- Story: The entire narrative, encompassing the conflicts, themes, and messages, answering the questions of Who, Why, and How.

8. Uncover the Power of Plot with WHAT.EDU.VN

Whether you meticulously plan your stories or prefer to discover them as you write, understanding plot is essential for effective storytelling.

Do you find yourself struggling to define the plot of your own story? Are you unsure how to structure your narrative or develop compelling conflicts?

Don’t let these challenges hold you back from crafting the story you envision. At WHAT.EDU.VN, we offer a platform where you can ask any question about storytelling, writing, or literature and receive insightful answers from experienced experts. Our community is dedicated to helping writers of all levels unlock their potential.

Here’s how WHAT.EDU.VN can help you:

- Get answers to your specific questions: No matter how niche or complex your query, our experts are ready to provide clear, concise, and helpful answers.

- Receive personalized guidance: Our community offers constructive feedback and support to help you refine your writing and develop your storytelling skills.

- Access a wealth of resources: Explore our extensive library of articles, tutorials, and resources on all aspects of writing.

Stop struggling in silence. Visit WHAT.EDU.VN today and ask your question. Let us help you unlock the power of plot and craft stories that captivate your audience.

Contact Us:

Address: 888 Question City Plaza, Seattle, WA 98101, United States

Whatsapp: +1 (206) 555-7890

Website: what.edu.vn