Pain is a universal human experience, yet its complexities often go misunderstood. Like the famous question posed in Cole Porter’s song, “What is this thing called love?”, we might ask, “What is this thing called pain?” While love remains largely enigmatic, significant strides have been made in recent years to unravel the mysteries of pain. This article will delve into the neurobiological perspective of pain, exploring its different classifications and shedding light on the critical question: What Is This Called when we experience various forms of discomfort?

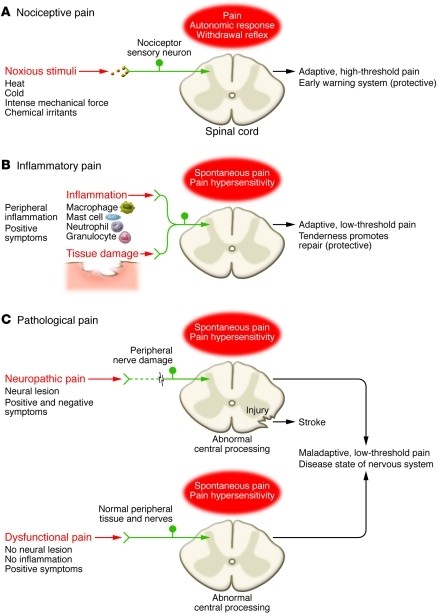

From a neurobiological standpoint, pain isn’t a singular entity. It’s crucial to recognize that pain manifests in at least three distinct forms, a distinction often overlooked in everyday language and even within medical contexts. These categories are not just semantic differences; they represent fundamentally different biological mechanisms, each with its own purpose and implications for treatment. Let’s explore these classifications to better understand, “what is this called?” in each case.

Nociceptive Pain: The Body’s Immediate Warning System

The first type of pain is the acute, sharp sensation you feel when you touch a hot stove or step on a sharp object. What is this called? This is nociceptive pain. Derived from the Latin word “nocere,” meaning “to harm,” nociceptive pain serves as an essential early-warning system, designed to protect us from immediate tissue damage. It’s triggered by noxious stimuli – intense heat, cold, pressure, or chemicals – that signal potential harm to the body.

Nociceptive pain represents the sensation associated with the detection of potentially tissue-damaging noxious stimuli and is protective.

Nociceptive pain represents the sensation associated with the detection of potentially tissue-damaging noxious stimuli and is protective.

Nociceptive pain is a high-threshold pain, meaning it only activates in response to intense stimuli. Its evolutionary roots trace back to the most primitive nervous systems, where the ability to detect and react to damaging environmental threats was crucial for survival. This protective role demands immediate attention and action. Nociceptive pain achieves this through:

- Withdrawal Reflex: An automatic, rapid movement to pull away from the source of pain.

- Unpleasant Sensation: The inherently aversive nature of the pain signal, prompting us to avoid the painful stimulus.

- Emotional Anguish: The emotional component of pain, further reinforcing avoidance behavior.

In essence, nociceptive pain is the body’s alarm system, overriding other neural functions to ensure immediate self-preservation.

Inflammatory Pain: Pain to Promote Healing

The second type of pain is also protective but operates on a different timescale. Think of the tenderness you feel around a sprained ankle or a surgical incision. What is this called? This is inflammatory pain. This type of pain arises after tissue damage has already occurred. Its purpose is to promote healing by inducing hypersensitivity in the injured area. This heightened sensitivity discourages movement and contact, allowing the damaged tissue to repair itself without further disruption.

Inflammatory pain is triggered by the body’s immune response to tissue injury or infection. Immune cells infiltrate the damaged area, releasing inflammatory mediators that sensitize the pain pathways. This results in pain hypersensitivity, where normally innocuous stimuli, like light touch, can now evoke pain. Inflammatory pain is, in fact, one of the classic signs of inflammation, alongside redness, heat, swelling, and loss of function.

While adaptive in the short term, prolonged inflammatory pain, as seen in conditions like rheumatoid arthritis or severe injuries, can become debilitating and require management.

Pathological Pain: When Pain Becomes the Disease

The third category of pain is distinct from the first two as it is no longer protective. Instead, it’s maladaptive, arising from abnormal functioning of the nervous system itself. What is this called? This is pathological pain. Unlike nociceptive and inflammatory pain, pathological pain is not a symptom of an underlying injury or inflammation; rather, it is considered a disease state of the nervous system.

Pathological pain can be further divided into two subcategories:

- Neuropathic Pain: This arises from damage to the nervous system itself, such as nerve injury due to trauma, surgery, or diseases like diabetes.

- Dysfunctional Pain: This occurs when there is no clear evidence of nerve damage or inflammation. Conditions like fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and tension headaches fall into this category.

Pathological pain is often characterized by central sensitization, where the central nervous system amplifies pain signals. This results in a low-threshold pain, meaning even mild stimuli can trigger significant pain. Using the fire alarm analogy, pathological pain is like a malfunctioning alarm system that goes off even when there is no fire.

Pathological pain represents a significant clinical challenge and is often the most difficult type of pain to treat effectively. Understanding its distinct mechanisms is crucial for developing targeted therapies.

The Importance of Understanding Pain Types

Recognizing these three distinct categories of pain – nociceptive, inflammatory, and pathological – is not just an academic exercise. It has profound implications for diagnosis and treatment. Because each type of pain is driven by different biological processes, effective pain management requires targeting the specific underlying mechanisms.

For instance, nociceptive pain is often effectively managed with simple analgesics or, in surgical settings, with anesthesia. Inflammatory pain may respond to anti-inflammatory medications. However, pathological pain, with its complex central nervous system involvement, often requires a multimodal approach, potentially including medications that modulate nerve activity, physical therapy, and psychological interventions.

In conclusion, when we ask “what is this called?” in the context of pain, the answer is not always straightforward. Pain is a multifaceted experience encompassing nociceptive, inflammatory, and pathological types, each with unique characteristics and biological underpinnings. Ongoing research continues to deepen our understanding of these distinctions, paving the way for more effective and personalized pain management strategies. By correctly identifying the type of pain, we can move closer to solving the mystery of pain and improving the lives of those who suffer from it.