Yellow journalism refers to a style of newspaper reporting that prioritized sensationalism and emotional appeal over factual accuracy. Flourishing at the end of the 19th century, this type of journalism played a significant role in shaping public opinion and is often cited as a contributing factor to the outbreak of the Spanish-American War in 1898. Through exaggerated stories and eye-catching headlines, yellow journalism captivated readers and influenced U.S. foreign policy, ultimately leading to the United States acquiring overseas territories.

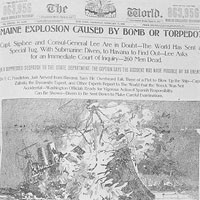

Example of Yellow Journalism in the cover of the Pulitzer’s World

Example of Yellow Journalism in the cover of the Pulitzer’s World

The Origins of “Yellow Journalism”: A Cartoon and a Newspaper War

The term “yellow journalism” emerged from a fierce circulation battle in New York City between two prominent newspaper magnates: Joseph Pulitzer, owner of the New York World, and William Randolph Hearst, who owned the New York Journal. Interestingly, the initial connection to “yellow” was not about journalistic ethics, but rather a popular comic strip. Richard F. Outcault’s “Hogan’s Alley,” depicting life in New York slums, became a sensation when published in color by Pulitzer’s World. The comic’s most famous character, known as “the Yellow Kid,” became incredibly popular, driving sales of the World significantly.

Recognizing the Yellow Kid’s appeal, Hearst lured Outcault away to his New York Journal in 1896, sparking a heated rivalry over the cartoonist. While Hearst ultimately secured Outcault, Pulitzer refused to concede, hiring another artist to continue the “Yellow Kid” strip for his paper. This intense competition over the “Yellow Kid” and newspaper market share is what gave birth to the label “yellow journalism.” The term soon expanded to describe the sensational and often unscrupulous reporting tactics employed by both Pulitzer and Hearst in their pursuit of profit and readership.

Cuba, Conflict, and Sensational Stories

The sensationalist approach of yellow journalism became particularly evident in the coverage of international events, most notably the escalating tensions in Cuba. As a long-time Spanish colony, Cuba had been experiencing ongoing movements for independence throughout the 19th century. These revolutionary sentiments intensified in the 1890s, drawing attention from the United States, where many citizens called for Spain to withdraw from the island, with some even offering support to Cuban revolutionaries.

Hearst and Pulitzer seized upon the Cuban struggle, dedicating increasing coverage to the unfolding events. Their newspapers frequently emphasized the brutality of Spanish rule and romanticized the Cuban revolutionaries’ fight for freedom. To boost readership, they often published exaggerated accounts, and sometimes outright fabrications, of Spanish atrocities. This coverage, characterized by bold, attention-grabbing headlines and dramatic illustrations, proved highly effective in selling newspapers and inflaming public opinion against Spain.

The USS Maine and the Peak of Yellow Journalism’s Influence

Yellow journalism reached its zenith in early 1898 with the sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor. The U.S. battleship had been dispatched to Havana as a show of force and as part of an effort to de-escalate tensions with Spain alongside a planned Spanish ship visit to New York. On February 15th, a massive explosion destroyed the Maine, sending it to the bottom of the harbor.

Initial investigations, including one by the Spanish colonial government, suggested an internal explosion on the ship. However, Hearst and Pulitzer, who had spent years cultivating anti-Spanish sentiment, immediately promoted theories of a Spanish plot to sink the Maine. When a U.S. naval inquiry later concluded that the explosion was likely caused by an external mine, yellow journalism outlets declared it an act of Spanish aggression and clamored for war. This intense media pressure contributed significantly to the rapid escalation of tensions, and by early May, the Spanish-American War had commenced.

The Legacy of Yellow Journalism

While yellow journalism undoubtedly contributed to the climate that led to the Spanish-American War and the subsequent expansion of U.S. influence, it was not the sole cause. Despite Hearst’s infamous (and possibly apocryphal) declaration, “You furnish the pictures, I’ll provide the war!”, other factors were at play. Yellow journalism amplified existing anti-Spanish feelings and capitalized on real events, rather than inventing them entirely. Furthermore, influential figures like Theodore Roosevelt were already advocating for U.S. expansionism.

Nevertheless, yellow journalism remains a crucial aspect of U.S. foreign relations history. Its role in the lead-up to the Spanish-American War demonstrates the power of the press to capture public attention and shape public reaction to international events. The sensational and often ethically questionable tactics of yellow journalism highlighted the significant influence media can wield in international affairs, a lesson that continues to resonate in the modern media landscape.