Buddhism, originating in northeastern India between the 6th and 4th centuries BCE, emerged during a period marked by significant social change and intense spiritual inquiry. This era witnessed a questioning of established Brahmanic traditions and rituals, with many seeking more personal and profound religious experiences. To understand What Is Buddhism, it’s essential to delve into its historical context and the core principles that have shaped this global religion.

At the time of Buddhism’s inception, India was experiencing considerable intellectual and spiritual ferment. Ascetic movements in northwestern India were challenging the rigid Vedic system, emphasizing inner spiritual development over external rituals. The Upanishads, texts from this movement, highlighted renunciation and transcendental knowledge. Northeastern India, less influenced by Vedic traditions, became a fertile ground for diverse new religious sects amidst social unrest and the fragmentation of tribal societies into smaller kingdoms. This environment of doubt and experimentation was crucial in the formation of what is Buddhism.

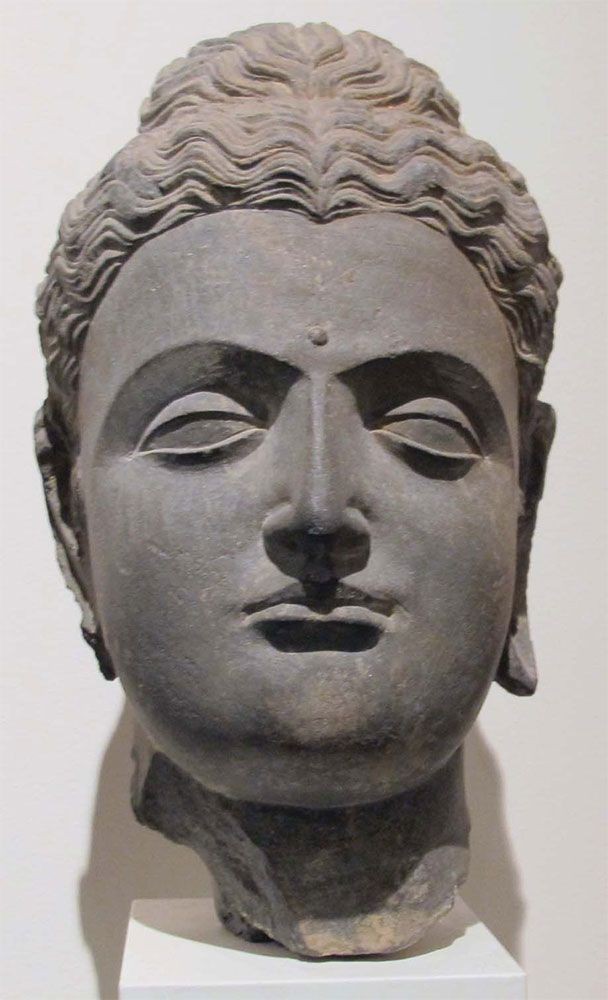

The 1st-3rd century CE schist sculpture of Buddha head shows Hellenistic Gandhara influences, currently housed in the Guimet Museum, Paris.

Various philosophical schools and sects flourished alongside early Buddhism. Proto-Samkhya ideas were prevalent, and new groups like skeptics, atomists, materialists, and antinomians emerged. Two particularly influential contemporary sects were the Ajivikas, emphasizing fate, and the Jains, focused on liberating the soul from matter. While often compared to atheism, the beliefs of Jains and early Buddhists were nuanced. Unlike early Buddhists, these groups often posited the permanence of the universe’s elements and the existence of a soul.

Despite the diversity of these religious communities, a shared vocabulary and set of practices were developing. Terms like nirvana, atman, yoga, karma, Tathagata, buddha, samsara, and dhamma became common currency, and the practice of yoga was widespread. The Buddha himself, according to tradition, was considered a yogi, known for ascetic practices and miracle-working abilities, which contributed to the early understanding of what is Buddhism.

Like many contemporary sects, Buddhism was characterized by a charismatic teacher, the Buddha, his promulgated teachings, and a community of followers comprising both renunciants and lay supporters. This structure is encapsulated in the Triratna, or “Three Jewels” of Buddhism: the Buddha (the enlightened teacher), the Dharma (his teachings), and the Sangha (the community of practitioners). These three elements are fundamental to what is Buddhism and its continued practice.

Over the centuries, Buddhism evolved and diversified. Two major branches emerged after the Buddha’s death. The Hinayana, later referred to as Theravada, meaning “Way of the Elders,” is considered more conservative. This school preserved early Buddhist teachings in collections like the Sutta Pitaka and Vinaya Pitaka, which remain normative texts. The Mahayana, or “Greater Vehicle,” recognized a broader range of teachings, believing them to offer paths to salvation for a wider population. Mahayana Buddhism accepted additional sutras, suggesting the Buddha revealed more advanced teachings to select disciples, expanding the scope of what is Buddhism.

As Buddhism spread across Asia and beyond, it adapted and interacted with various cultures and philosophical systems. In some Mahayana traditions, interpretations of karma were modified to incorporate ritual actions and devotional practices. By the second half of the 1st millennium CE, Vajrayana, the “Diamond Vehicle” or Tantric Buddhism, developed in India. Influenced by gnostic and magical trends, Vajrayana aimed for a faster path to spiritual liberation, further diversifying what is Buddhism and its practices.

Despite these diverse developments and adaptations, Buddhism maintained its core principles. These principles were continuously reinterpreted and reformulated, resulting in a vast body of literature. This includes the Pali Tipitaka, encompassing the Sutta Pitaka (Buddha’s sermons), the Vinaya Pitaka (monastic rules), and the Abhidhamma Pitaka (doctrinal analysis). Mahayana and Vajrayana traditions expanded this canon with numerous sutras, tantras, treatises, and commentaries. This continuous evolution and reinterpretation around a central philosophical and ethical nucleus are key to understanding what is Buddhism and its enduring global influence from its origins in Sarnath to its contemporary forms.