Introduction

The term “hypersexuality” has emerged in modern discourse, particularly within clinical settings, to describe a complex condition characterized by an amplified sexual drive that leads individuals to seek sexual gratification in ways that are often inappropriate and ultimately unsatisfying. This concept has gained traction in the scientific community as a more clinically relevant and less stigmatizing alternative to older terms like nymphomania (for women) and satyriasis (for men) [1]. These antiquated terms, rooted in Greek mythology and referencing figures known for their unrestrained sexual appetites, fail to capture the nuanced and often distressing nature of hypersexuality as understood today.

While the mythical nymphs and satyrs were figures of legend, their names were historically used to label what was seen as a morbid exaggeration of sexual impulses. This perception persisted for centuries, influencing art and storytelling. The shift towards a more clinical understanding began in the 18th century, notably with French physician Giambatist De Bienville’s 1771 work, “Nymphomania. Treatise on Uterine Fury” [2], marking an early attempt to analyze these behaviors from a medical perspective.

Today, hypersexuality is recognized within the framework of contemporary psychiatric classifications, appearing in both the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) [3] and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR) [4]. The ICD, published by the World Health Organization, serves as a global standard for classifying diseases, including a dedicated section for mental disorders. The DSM-5-TR, from the American Psychiatric Association, is the most widely used diagnostic manual in mental health within the international scientific community. However, despite their significance, these systems reflect ongoing challenges in defining and categorizing hypersexuality. In ICD-11, hypersexuality falls under “Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder” (code 6C72), while DSM-5-TR considers it a behavioral addiction, or a symptom of other underlying disorders. This discrepancy highlights the complexities and ongoing debate surrounding hypersexuality as a distinct clinical entity.

Understanding what hypersexuality is, its potential causes, and how it manifests is crucial for individuals, clinicians, and researchers alike. This article delves into the current understanding of hypersexuality, exploring its definition, diagnostic criteria, potential etiologies, and the proposed Perrotta Hypersexuality Global Spectrum of Gradation (PH-GSS) as a tool for better assessment and management.

Defining Hypersexuality: Clinical Profiles and Diagnostic Criteria

Hypersexuality, in its modern clinical context, is characterized by persistent and excessive sexual thoughts, urges, and behaviors that cause significant distress or impairment in various aspects of life. It is more than just a high libido; it involves a compulsion and lack of control that negatively impacts an individual’s well-being and functioning.

Both the ICD-11 and DSM-5-TR acknowledge hypersexuality, although with slightly different approaches. The ICD-11 provides specific diagnostic criteria for “Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder,” which is often used interchangeably with hypersexuality. These criteria offer a structured framework for identifying the condition. According to the World Health Organisation, the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria for compulsive sexual behaviour disorder (hypersexuality) include the following, which must be present for at least six months:

(A) Recurrent and intense sexual fantasies, sexual urges, or sexual behaviour, alongside at least three of the following:

- Time Consumption: Excessive time spent engaging in sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors that significantly encroaches on other important life goals, activities, and obligations.

- Mood Regulation: Repetitive engagement in sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors as a response to negative emotional states such as anxiety, depression, boredom, or irritability.

- Stress Response: Repetitive engagement in sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors as a reaction to stressful life events.

- Control Failure: Persistent but unsuccessful attempts to control or significantly reduce these fantasies, urges, or behaviors.

- Risk Disregard: Repeated engagement in sexual behaviors despite the risk of physical or emotional harm to oneself or others.

(B) Clinically significant distress or impairment: The individual experiences considerable personal distress or functional impairment in social, occupational, or other crucial areas of life directly linked to the frequency and intensity of these sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors.

(C) Exclusion of other conditions: These sexual fantasies, urges, or behaviors are not directly caused by medical conditions (like brain tumors or dementia) or substance use (including substance abuse or medication side effects) [3,5].

It’s crucial to note that these criteria emphasize the loss of control, distress, and functional impairment associated with hypersexual behaviors, distinguishing it from simply having frequent sexual thoughts or a high sex drive. The focus is on the compulsive nature of the behavior and its negative consequences on the individual’s life.

Is Hypersexuality a Disorder? Understanding its Clinical Relevance

The question of whether hypersexuality is a distinct clinical disorder or a symptom of other underlying conditions remains a subject of ongoing debate. While diagnostic manuals like the ICD-11 recognize “Compulsive Sexual Behaviour Disorder,” the precise nature and classification of hypersexuality are still being explored.

A significant point of discussion is whether hypersexuality is a primary or secondary condition. The prevailing view leans towards hypersexuality being secondary – meaning it often arises as a consequence of other underlying medical, neurological, or psychiatric issues. This perspective is supported by the diverse range of conditions associated with hypersexual behaviors.

Conditions Linked to Hypersexuality:

-

Neurological Conditions: Several neurological conditions have been linked to hypersexuality, including:

- Klüver-Bucy syndrome: Resulting from bilateral damage to the amygdala, this syndrome can manifest with hypersexuality alongside other symptoms.

- Dementias: Various forms of dementia, particularly those affecting the frontal and temporal lobes, such as frontotemporal dementia and Pick’s disease, can lead to disinhibited behaviors including hypersexuality.

- Kleine-Levin Syndrome: Also known as “Sleeping Beauty syndrome,” this rare disorder is characterized by episodes of hypersomnia, cognitive disturbances, and sometimes, hypersexuality.

- Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD): While not always present, hypersexuality can occur in some individuals with ASD.

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Studies suggest a link between ADHD and hypersexuality, potentially due to impulsivity and difficulties with self-regulation [7,8,10,13,16,20,23,30,31,32,33,34].

-

Psychiatric Disorders: Hypersexuality is frequently observed in the context of various psychiatric disorders:

- Bipolar Disorder: During manic or hypomanic phases, individuals with bipolar disorder may exhibit increased libido, impulsivity, and hypersexual behaviors.

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): Impulsivity and emotional dysregulation in BPD can contribute to hypersexual behaviors as a coping mechanism or manifestation of emotional distress.

- Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) Spectrum: While the relationship is complex, some individuals may exhibit compulsive sexual behaviors that share features with OCD.

- Behavioral Addictions: Hypersexuality itself is sometimes considered a behavioral addiction, characterized by compulsive engagement in sexual activities despite negative consequences.

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Certain personality disorders, particularly covert narcissism, may be associated with hypersexual behaviors as a means of seeking validation or regulating self-esteem [9,11,12,21,24,25,27,35,36,37,38,39].

-

Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI): Trauma to brain regions involved in impulse control and emotional regulation, particularly the frontal and temporal lobes and limbic system, can lead to hypersexuality [40].

-

Substance Use and Medications:

- Stimulant Drugs: Substances like methamphetamine, cocaine, and synthetic drugs can induce or exacerbate hypersexual behaviors due to their effects on the brain’s reward system.

- Dopaminergic Medications: Drugs like L-dopa, used in Parkinson’s disease, and prolactin inhibitors can increase dopamine levels, potentially leading to impulsive behaviors, including hypersexuality. Dopamine’s role in reward pathways may explain this link [17,26].

- Anabolic Steroids and Sex Hormones: Testosterone and other sex hormones can influence libido and, in some cases, contribute to hypersexual behaviors.

Understanding hypersexuality as potentially secondary to other conditions highlights the importance of thorough assessment to identify and address underlying factors. Effective management often requires a multidisciplinary approach, incorporating psychotherapy and, in some cases, psychopharmacological interventions tailored to the individual’s specific needs and co-occurring conditions.

Exploring the Causes of Hypersexuality: Etiopathological Theories

While the exact causes of hypersexuality are still being investigated, several etiological theories attempt to explain its development. These theories offer different perspectives, ranging from psychological and behavioral models to neurobiological explanations.

1. Compulsive Model:

This model proposes that hypersexuality is a manifestation of obsessive-compulsive tendencies. According to this view, sexual fantasies become obsessions – intrusive and recurrent thoughts that cause anxiety. Compulsions, in this context, are the sexual behaviors themselves, performed to reduce the anxiety associated with the obsessions. The sexual act, whether masturbation or intercourse, is seen as a way to release libidinal drive, particularly during times of stress.

However, a key distinction between hypersexuality and traditional OCD lies in egosyntonicity. In hypersexuality, the sexual thoughts and behaviors are often perceived as aligned with the individual’s desires and self-image, at least initially. They may not be experienced as intrusive or unwanted in the same way as typical OCD obsessions. Individuals with OCD, on the other hand, generally recognize their obsessions as distressing and intrusive. This difference suggests that hypersexuality may not neatly fit within the category of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders as traditionally defined.

2. Impulsive Model:

The impulsive model, favored by the World Health Organization, frames hypersexuality as an impulse control disorder. This perspective emphasizes the individual’s perceived inability to manage sexual impulses. The core idea is that the hypersexual person experiences overwhelming sexual urges and acts on them without adequate forethought or modulation. This is thought to be driven by an inability to delay gratification, leading to immediate action to relieve sexual tension, often followed by feelings of guilt or regret. A presumed dysfunction in the frontal lobe, responsible for executive functions and impulse control, is often cited as a potential neurobiological basis for this impulsivity.

However, this model has been challenged by observations of hypersexual individuals’ behavior. While the initial impulse may indeed be strong and difficult to resist, the planning and execution of hypersexual activities are often not impulsive at all. Many individuals engage in elaborate planning and methodical approaches to seeking out and engaging in sexual behaviors, suggesting a level of organization and premeditation that contradicts the purely impulsive nature of the disorder.

3. Addiction Model (Neurobiological):

The addiction model posits that hypersexuality is a behavioral addiction, sharing key characteristics with substance use disorders and other behavioral addictions. These characteristics include:

- Tolerance: A need to increase the intensity or frequency of sexual activity to achieve the same level of satisfaction.

- Withdrawal: Experiencing negative emotional and physical symptoms (like anxiety, rumination, guilt) when sexual activity is reduced or absent.

- Loss of Control: Difficulty in controlling or reducing sexual behaviors despite attempts to do so.

- Preoccupation: Spending excessive time seeking sexual partners, planning sexual activities, or recovering from sexual encounters.

- Neglect of Other Activities: Reduced participation in social, occupational, and recreational activities due to the overwhelming focus on sexual pursuits.

- Continued Use Despite Negative Consequences: Persisting with sexual behaviors despite experiencing negative impacts on personal relationships, work, health, or social life.

This model gains further support from neurobiological research. Neuroimaging studies have revealed dysregulation in the dopaminergic and serotonergic systems in individuals with hypersexuality, mirroring the neurochemical imbalances seen in substance addictions. The dopamine neurotransmitter, released by neurons in the limbic system (specifically the nucleus accumbens), plays a crucial role in reward and motivation. In hypersexuality, it’s theorized that dopamine release is dysregulated, leading to an exaggerated reward response to sexual stimuli and contributing to compulsive sexual seeking. Dysfunction in the mesolimbic-dopaminergic and nigrostriatal pathways, key components of the brain’s reward circuitry, has been implicated in both impulse control disorders and obsessive-compulsive disorder, further linking these concepts to hypersexuality.

The serotonergic system, involved in mood regulation, satiety, and impulse control, is also being investigated for its potential role in hypersexuality. Similarly, oxytocin, a hormone involved in social bonding and attachment, is considered a potential factor, although its precise role in hypersexuality requires further research [42,43,44]. Understanding the neurobiological underpinnings of hypersexuality is crucial for developing targeted and effective treatments.

4. Psychotraumatic Model:

This model emphasizes the role of past traumatic experiences in the development of hypersexuality. It suggests that hypersexual behaviors can emerge as a dysfunctional coping mechanism in response to trauma, particularly childhood trauma. Psychometric instruments like the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ) are used to assess the presence and impact of early traumatic experiences in individuals with hypersexuality [22,26,45]. Trauma can disrupt healthy emotional development and coping strategies, potentially leading individuals to use sexual behaviors as a way to manage emotional distress, regulate affect, or seek a sense of control or power.

These various etiological models are not mutually exclusive, and it’s likely that hypersexuality is a complex condition with multiple contributing factors. A comprehensive understanding requires considering psychological, behavioral, and neurobiological perspectives, as well as individual experiences and vulnerabilities.

The Spectrum of Hypersexuality: Introducing the PH-GSS Scale

Current diagnostic approaches to hypersexuality, while providing a framework, often fail to capture the spectrum and varying degrees of severity of the condition. A significant limitation is the lack of clear differentiation between different forms of hypersexuality and the absence of a graded scale to assess the level of functional impairment. To address this gap, the Perrotta Hypersexuality Global Spectrum of Gradation (PH-GSS) has been proposed as a more nuanced and comprehensive assessment tool.

The PH-GSS aims to categorize hypersexuality along a spectrum, distinguishing between high-functioning forms and those characterized by more severe dysfunction and pathology. This scale recognizes that hypersexual behaviors exist on a continuum, and not all manifestations are equally detrimental or clinically relevant.

The Perrotta Hypersexuality Global Spectrum of Gradation (PH-GSS):

The PH-GSS scale is divided into five levels, categorized into high-functioning pathological, pathological attenuated functioning, and pathological to corrupt functioning. Each level is associated with a color and a definition describing the behavior and functional impact.

High-Functioning Pathological:

| Level | Colour | Definition | Behavior ## Table 1.

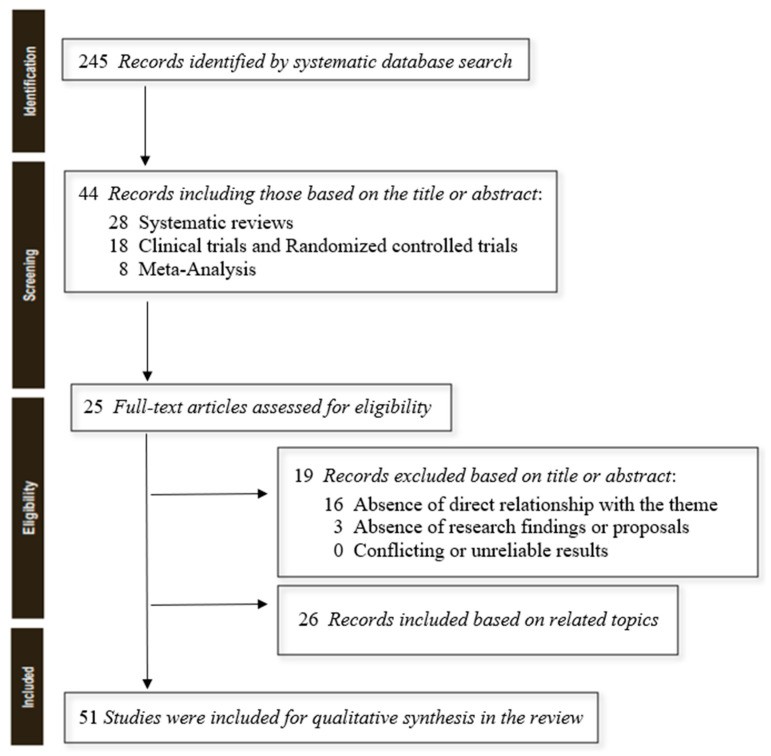

Selected manuscripts on the theme of hypersexuality. RES (clinical trial or randomised controlled trial); M (meta-analysis); R (review and systematic review); E (editorial).

2. Diagnosis and Assessment of Hypersexuality

Diagnosing hypersexuality presents several challenges due to the subjective nature of sexual desire and behavior, and the overlap with other conditions. There is no single, universally accepted diagnostic tool, but assessment typically involves a comprehensive clinical evaluation that may include:

- Clinical Interview: A detailed discussion with a mental health professional to understand the individual’s sexual history, patterns of behavior, associated distress, and functional impairment.

- Psychological Questionnaires and Scales: Various psychometric instruments can aid in assessing different aspects of hypersexuality:

- Hypersexual Disorder Screening Inventory (HDSI): Designed to screen for hypersexual disorder and assesses symptoms aligned with DSM criteria [5].

- Sexual Addiction Screening Test (SAST) and Sexual Compulsivity Scale (SCS): Focus on the compulsive aspects of sexual behavior, evaluating loss of control and addictive patterns [5].

- Hypersexual Behavior Inventory (HBI): A self-report measure assessing the frequency and intensity of hypersexual behaviors [5].

- Sex-relation Evaluation Schedule Assessment Monitoring (SESAMO): Explores sexual and relational aspects, providing a broader context for understanding the individual’s sexual functioning [5].

- Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ): Used to investigate potential links between childhood trauma and hypersexual behavior [22].

It is essential to rule out other potential causes of excessive sexual behavior, such as underlying medical conditions, substance use, or medication side effects, as outlined in the ICD-11 diagnostic criteria. Differential diagnosis is crucial to distinguish hypersexuality from other psychiatric disorders like bipolar disorder, borderline personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, where hypersexual behavior may be a symptom rather than the primary issue.

The PH-GSS scale, as described earlier, offers a valuable framework for assessing the severity and functional impact of hypersexuality, going beyond a simple diagnosis to provide a more nuanced understanding of the individual’s condition.

3. Treatment Approaches for Hypersexuality

Treatment for hypersexuality typically involves a multidisciplinary approach tailored to the individual’s specific needs and the severity of their condition. Common treatment modalities include:

-

Psychotherapy: Psychotherapy is often the cornerstone of hypersexuality treatment. Effective approaches include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT helps individuals identify and modify maladaptive thoughts and behaviors associated with hypersexuality. It focuses on developing coping skills, managing urges, and changing dysfunctional patterns [18,19].

- Psychodynamic Therapy: Explores underlying emotional and psychological factors contributing to hypersexual behavior, often focusing on past experiences and relationship patterns.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT): ACT helps individuals accept uncomfortable thoughts and feelings associated with urges while committing to values-based actions that are not driven by compulsive behaviors.

- Group Therapy: Provides a supportive environment where individuals can share experiences, reduce isolation, and learn from others facing similar challenges.

-

Psychopharmacological Treatment: Medication may be considered in conjunction with psychotherapy, particularly when co-occurring conditions are present or when symptoms are severe. Medications used can include:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): Antidepressants that can help manage compulsivity and co-occurring mood disorders.

- Mood Stabilizers: Used if hypersexuality is associated with bipolar disorder or significant mood swings.

- Anti-androgens: Medications that reduce testosterone levels, which may be helpful in some cases, particularly for men with severe hypersexuality or paraphilic behaviors.

- Naltrexone: An opioid antagonist that has shown promise in treating various behavioral addictions, including hypersexuality, by reducing cravings and reward responses.

- Anxiolytics and Antipsychotics: May be used to manage co-occurring anxiety, agitation, or psychotic symptoms in certain cases [15,41].

-

Support Groups: Self-help groups like Sex Addicts Anonymous (SAA) and similar organizations offer peer support and a structured program for recovery.

Treatment planning should be individualized, taking into account the PH-GSS level, co-existing mental health conditions, personal history, and treatment preferences. A comprehensive approach that combines therapy, potential medication, and support systems is often the most effective path to managing hypersexuality and improving overall well-being.

Conclusion: Towards a More Nuanced Understanding of Hypersexuality

Hypersexuality is a complex and multifaceted condition that goes beyond simply having a high sex drive. It is characterized by compulsive sexual thoughts, urges, and behaviors that cause significant distress and impairment in an individual’s life. While diagnostic criteria exist, the field is still evolving in its understanding of hypersexuality as a distinct clinical entity.

This review has highlighted the ongoing debate surrounding the definition, causes, and classification of hypersexuality. The proposed Perrotta Hypersexuality Global Spectrum of Gradation (PH-GSS) represents a significant step forward in moving beyond categorical diagnoses towards a more nuanced, spectrum-based approach. By grading hypersexuality according to functional impairment, the PH-GSS offers clinicians a more practical and clinically relevant tool for assessment and treatment planning.

Future research is crucial to further elucidate the etiopathology of hypersexuality, particularly the role of neurobiological factors like oxytocin and dopamine. Understanding the interplay between personality structures, trauma, and neurochemistry will be essential for developing more targeted and effective therapies. Continued investigation into the effectiveness of different treatment modalities, including psychotherapy and pharmacological interventions, is also needed to optimize clinical practice.

Ultimately, a deeper and more nuanced understanding of hypersexuality is essential to reduce stigma, improve diagnostic accuracy, and provide individuals struggling with compulsive sexual behaviors with the effective and compassionate care they need. The PH-GSS scale and ongoing research efforts pave the way for a more comprehensive and helpful approach to this complex condition.

Implications for Clinical Practise

The systematic gradation of hypersexuality, as proposed by the PH-GSS, offers significant implications for clinical practice. It provides a structured framework for clinicians to move beyond subjective interpretations and assess the severity of hypersexuality in a more objective and functionally relevant manner. This allows for more tailored treatment planning, ensuring that interventions are appropriately matched to the individual’s level of impairment. By distinguishing between different levels of hypersexuality, the PH-GSS helps clinicians avoid over-pathologizing individuals with higher sexual drive within a physiological range, while also identifying and providing targeted support for those with truly dysfunctional and pathological hypersexuality. This refined approach can enhance the clinical dignity of addressing hypersexuality, moving away from simplistic labels and towards a more comprehensive and individualized understanding of each patient’s experience.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Funding Statement

This work received no external funding.

Footnotes

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.