What Is The Plot, and how does it drive a narrative? At WHAT.EDU.VN, we unravel the complexities of story plotting, offering insights into plot development, plot structure, and the art of crafting a compelling narrative arc. From understanding causation to mastering plot devices, discover how to create stories that captivate and resonate with your audience. Explore narrative structure, story components, and storyline creation.

1. Plot Definition: Unveiling the Essence of Story Plot

The plot of a story is the intentional sequencing of events, each intricately linked, propelling the narrative forward from its inception to its conclusion. Each event within the plot acts as a catalyst, influencing and shaping the events that follow, creating a cohesive and engaging narrative journey. The plot constitutes a carefully constructed chain of cause-and-effect relationships, weaving together the various elements of the story into a unified whole.

What is plot?: A series of causes-and-effects which shape the story as a whole.

Understanding the plot requires more than just summarizing the story; it demands recognizing the causal connections between events. The celebrated novelist E. M. Forster elucidates this distinction:

“The king died and then the queen died is a story. The king died, and then the queen died of grief, is a plot.” —E. M. Forster

The addition of “of grief” transforms a mere sequence of events into a plot by introducing causality. Without this element, the queen’s death could be attributed to various unrelated reasons. Grief not only provides structure to the plot but also introduces potential themes, such as love, loss, and the consequences of power.

1.1. Essential Components That Define A Plot

A well-crafted plot consists of several key elements, each contributing to the story’s overall impact:

- Causation: The cornerstone of plot, where one event precipitates another, setting off a chain reaction that drives the narrative forward. This cause-and-effect relationship forms the backbone of the story.

- Characters: Stories revolve around people, and the plot must introduce the main characters. The plot should showcase characters’ relationships, motivations, and development throughout the story.

- Conflict: The lifeblood of storytelling, conflict introduces opposing forces or internal struggles that characters must confront. Without conflict, there is no tension, no stakes, and no story. Conflict can be external (character vs. character, character vs. society) or internal (character vs. self).

These elements, when artfully combined, form the bedrock of the story’s structure, dictating how events unfold and how characters evolve in response to the challenges they face.

Plot is people. Human emotions and desires founded on the realities of life, working at cross purposes, getting hotter and fiercer as they strike against each other until finally there’s an explosion—that’s Plot. —Leigh Brackett

2. Plot Structure: Common Frameworks for Narrative Construction

Throughout history, storytellers have experimented with various plot structures to create engaging and memorable narratives. Understanding these common structures can help you organize your ideas and overcome challenges in your own writing.

2.1. Aristotle’s Story Triangle: The Foundational Structure

Aristotle’s Poetics (circa 335 B.C.) offers one of the earliest recorded discussions of plot structure. He conceptualized the plot as a narrative triangle, proposing that stories follow a linear progression that resolves conflicts in three distinct parts: a beginning, middle, and end.

According to Aristotle, the beginning should be independent of prior events, a self-contained unit that doesn’t leave the reader questioning “why?” or “how?”. The middle should logically follow the beginning, expanding on the story’s conflicts and building tension. Finally, the end should provide a satisfying resolution, without hinting at further events.

While many stories deviate from this basic structure, Aristotle’s triangle provides a fundamental framework for understanding narrative construction. Freytag’s Pyramid builds upon Aristotle’s ideas by adding more detail to plot structure.

2.2. Freytag’s Pyramid: A Five-Act Structure

Freytag’s Pyramid expands on Aristotle’s ideas by dividing the plot into five distinct parts:

- Exposition: The story’s beginning, introducing the main characters, setting, themes, and the author’s writing style.

- Rising Action: Initiated by the inciting incident, the event that sets the story’s main conflict in motion. The rising action follows the cause-and-effect chain of events as the conflict intensifies.

- Climax: The story’s turning point, where the conflict reaches its peak, and the fate of the main characters is revealed.

- Falling Action: The events following the climax, where the main characters react to and grapple with the consequences of the climax.

- Denouement: The story’s resolution, where any remaining loose ends are tied up. Some stories have open-ended denouements that leave the reader with questions.

For a more in-depth look at Freytag’s Pyramid, visit WHAT.EDU.VN.

2.3. Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc: A Detailed Progression

Nigel Watts’ 8 Point Arc further elaborates on Freytag’s Pyramid, suggesting that a story must progress through eight specific plot points:

- Stasis: The protagonist’s everyday life before the story’s inciting incident disrupts their routine.

- Trigger: An event beyond the protagonist’s control sets the story’s conflict in motion.

- The Quest: Akin to the rising action, the quest is the protagonist’s journey to confront the story’s conflict.

- Surprise: Unexpected moments during the quest that complicate the protagonist’s journey. This could be an obstacle, complication, confusion, or internal flaw.

- Critical Choice: The protagonist must make a life-altering decision that reveals their true character and significantly impacts the story’s events.

- Climax: The result of the protagonist’s critical choice, the climax determines the consequences of that choice and represents the story’s highest point of tension.

- Reversal: The protagonist’s reaction to the climax, which alters their status, whether that status is their place in society, their outlook on life, or their own death.

- Resolution: The return to a new stasis, where a new life emerges from the ashes of the story’s conflict and climax.

Watts expands on this plot structure in his book Write a Novel and Get It Published.

2.4. Save the Cat: A Screenwriting-Focused Structure

Developed by screenwriter Blake Snyder, the Save the Cat plot structure offers a detailed roadmap for storytelling. While primarily designed for screenplays, its principles can be applied to various types of stories.

The Save the Cat structure breaks down the story into fifteen “beats,” or key events, that guide the narrative from beginning to end. These beats include the opening image, theme stated, set-up, catalyst, debate, break into two, B story, fun and games, midpoint, bad guys close in, all is lost, dark night of the soul, break into three, finale, and final image.

Visit Reedsy for a comprehensive breakdown of Save the Cat, including a worksheet you can use to draft your own story.

2.5. The Hero’s Journey: A Mythic Structure

The Hero’s Journey, developed by Joseph Campbell, posits that stories follow a universal pattern centered around a hero’s transformation. Campbell argued that the plot of a story has three main acts, with each act corresponding to the necessary journey a hero must undergo in order to be the hero.

These three parts are: Stage 1) The Departure Act (the hero leaves their everyday life); Stage 2) The Initiation Act (the hero undergoes various conflicts in an unknown land); and Stage 3) The Return Act (the hero returns, radically altered, to their original home).

Christopher Vogler expanded on these three stages in his screenwriting textbook The Writer’s Journey, outlining a 12-step process:

The Departure Act

- The Ordinary World: The hero is introduced in their mundane, everyday reality.

- Call to Adventure: The hero is presented with a challenge that compels them to leave their ordinary world.

- Refusing the Call: Recognizing the dangers of adventure, the hero hesitates or refuses the call.

- Meeting the Mentor: The hero gains a mentor who provides guidance and support.

The Initiation Act

- Crossing the Threshold: The hero leaves their known world and enters a new, unfamiliar one.

- Tests, Allies, and Enemies: The hero faces challenges, encounters allies, and confronts enemies.

- Approach (to the Inmost Cave): The hero prepares to face their greatest challenge.

- Ordeal: The hero faces a major crisis or test, often resulting in a low point.

- Reward: The hero receives a reward or gains something of value.

The Return Act

- The Road Back: The hero begins their journey back home.

- Resurrection: The hero faces a final, climactic challenge.

- The Return: The hero returns home transformed, bringing their reward or knowledge with them.

2.6. Fichtean Curve: Rising Action Emphasis

The Fichtean Curve, originally designed for pulp and mystery stories, emphasizes the rising action. John Gardner described it extensively in The Art of Fiction, arguing that a story plot has three parts: a rising action, a climax, and a falling action.

In the Fichtean Curve, the rising action comprises about ⅔ of the entire story. Moreover, the rising action isn’t linear. Rather, a series of escalating and de-escalating conflicts slowly pushes the story towards its climax.

3. Conflict: The Driving Force of Narrative

Conflict is an essential element of any compelling plot. It is the opposition that characters face, whether external or internal, that drives the story forward and creates tension. Conflict is not necessarily two characters bickering, although that’s certainly an example. Conflict refers to the opposing forces acting against a character’s goals and interests. Sometimes, that conflict is external: an enemy, bureaucracy, society, etc. Other times, the conflict is internal: traumas, illogical ways of thinking, character flaws, etc.

3.1. Types of Conflict

- External Conflict: Conflict between a character and an outside force, such as another character, society, or nature.

- Internal Conflict: Conflict within a character’s own mind, such as a moral dilemma, a struggle with their own identity, or overcoming a personal flaw.

3.2. The Role of Conflict in Plot

Conflict is the engine of the story. It’s what incites the inciting incident. It’s what keeps the rising action rising. The climax is the final product of the conflict, and the denouement decides the outcome of that conflict. The plot of a story relies on conflict to keep the pages turning.

If you’re struggling to develop your plot, always return to conflict. Each scene should advance a conflict, even if the conflict is not immediately apparent. Anything that doesn’t explore, expand, or resolve the elements of a story’s conflict is likely wasting the reader’s time.

If you’re developing a story plot, but don’t know where to go, always return to conflict.

3.3. Alternative Perspectives on Conflict

The emphasis on conflict in plot is largely a Western concept. Some storytelling traditions, such as the Eastern story structure Kishōtenketsu, focus on characters reacting to external situations rather than generating and resolving their own conflicts. In these stories, the characters themselves, their complexities and dilemmas, and how they survive in a world they can’t control, are the primary focus.

To learn more about conflict in story plot, check out our article:

What is Conflict in a Story? Definition and Examples

4. Plot Devices: Tools for Enhancing Narrative

Plot devices are techniques that authors use to manipulate the story’s events, create suspense, and engage the reader. These devices can add depth, complexity, and surprise to your narrative.

4.1. Aristotle’s Plot Devices

In Poetics, Aristotle identified three essential plot devices:

- Anagnorisis (Recognition): The moment when the protagonist realizes a crucial piece of information, often leading to a turning point in the story.

- Pathos (Suffering): The experience of pain or suffering, whether physical or emotional, that is essential for propelling the plot.

- Peripeteia (Reversal): A sudden change in fortune, from good to bad or vice versa, that often accompanies anagnorisis.

4.2. Plot Devices for Structuring the Story

- Backstory: Events that occurred before the main story, providing context and character development.

- Deus Ex Machina: A sudden, unexpected intervention that resolves the story’s conflict, often viewed as a convenient but unsatisfying resolution.

- In Media Res: Starting the story in the middle of the action, immediately grabbing the reader’s attention.

- Plot Voucher: An item, piece of information, or alliance that is introduced early in the story but becomes important later on.

4.3. Plot Devices for Complicating the Story

- Cliffhanger: Ending the story at a moment of high tension, leaving the reader eager to know what happens next.

- MacGuffin: An object or goal that drives the plot but lacks intrinsic value, often serving as a distraction from the true motivations of the characters.

- Red Herring: A misleading clue or detail that distracts the reader from the truth, commonly used in mystery and suspense stories.

For more plot devices and storytelling techniques, take a look at our article The Art of Storytelling on WHAT.EDU.VN.

5. Types of Plots: Recurring Narrative Patterns

Certain plot types appear frequently in literature, especially in genre fiction. These plots follow established conventions and archetypes, providing a familiar framework for storytelling.

5.1. Quest

The protagonist embarks on a journey in search of something, such as treasure, love, truth, a new home, or the solution to a problem. The protagonist returns from their quest stronger, smarter, and irreversibly changed.

5.2. Tragedy

A well-meaning protagonist fails to resolve the story’s conflict due to their flaws or shortcomings, often resulting in a moral or personal loss.

5.3. Rags to Riches

A protagonist rises from poverty to wealth, navigating issues of class, identity, and the corrupting influence of money.

5.4. Story Within a Story

A second story is embedded within the main narrative, reflecting or complicating the themes of the main story.

5.5. Parallel Plot

Two or more concurrent plots are told side-by-side, influencing each other and contributing equally to the overall story.

5.6. Rebellion Against “The One”

A hero resists the oppressive force of an omnipotent antagonist, often ending in submission or death.

5.7. Anticlimax

The story details the falling action after a climax that has already occurred, focusing on the aftermath and consequences of the climax.

5.8. Voyage and Return

The protagonist journeys into a strange world, achieves a daring act, and returns home transformed by their experiences.

6. Plot-Driven vs. Character-Driven Stories: A Matter of Emphasis

A common distinction is whether the story is “plot driven” or “character driven.” This refers to whether the plot of a story defines the characters, or whether the characters define the plot of a story.

Generally, a piece of literary fiction will have the characters in control of the plot, as the story’s plot points are built entirely off of the decisions that those characters make and the influences of those characters’ personalities.

Genre fiction, by contract, tends to have predefined plot structures and archetypes, and the characters must fit into those structures in order to tell a complete story.

6.1. Balancing Plot and Character

While this general distinction helps organize the qualities of fiction, don’t treat them as absolutes. Literary fiction borrows plot devices from genre fiction all the time, and there are many examples of genre fiction that are character driven. Your story should build a working relationship between the characters and the plot, as both are essential elements of the storyteller’s toolkit.

Your story should build a working relationship between the characters and the plot, as both are essential elements of the storyteller’s toolkit.

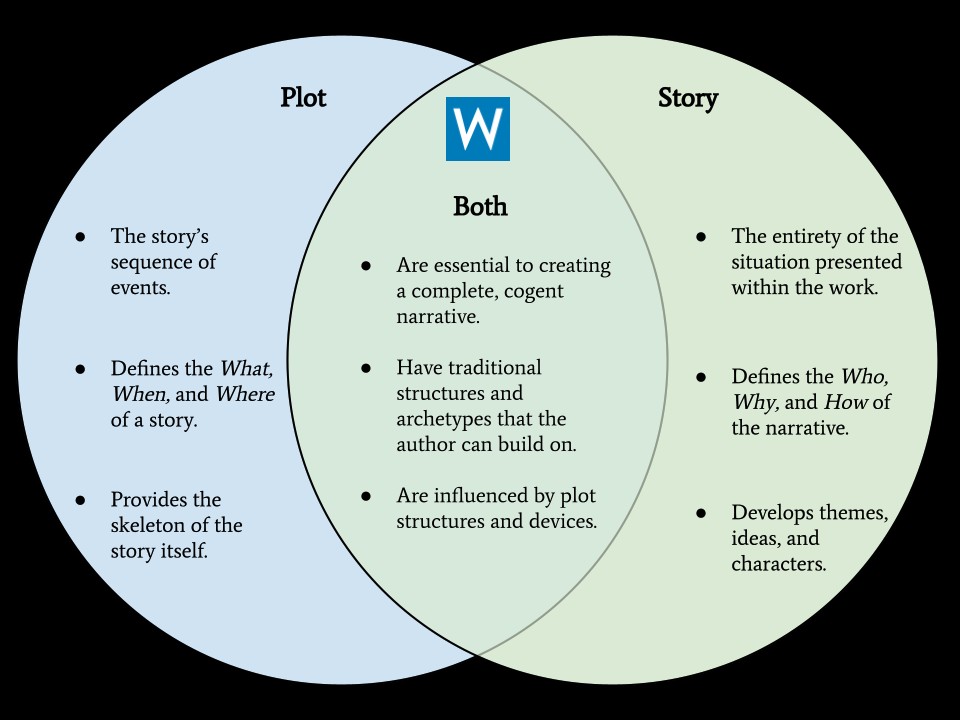

7. Plot vs. Story: Defining the Difference

The terms “plot” and “story” are often used interchangeably, but they have distinct meanings.

7.1. Plot Definition

The story’s sequence of events, focusing on the What, When, and Where of the narrative. What happens (and what is the cause-and-effect), when does it happen, and where is it happening?

7.2. Story Definition

The entirety of the work, including its conflicts, themes, and messages. In addition to plot, the story answers questions of Who, Why, and How. Who is involved (and who are they psychologically), why does this conflict happen, and how do the characters resolve the conflict?

To learn more about writing a cogent story from a compelling plot, read our article on the topic on WHAT.EDU.VN.

8. Unlock Your Storytelling Potential with WHAT.EDU.VN

Whether you’re a plotter who meticulously plans every detail or a pantser who writes by the seat of their pants, WHAT.EDU.VN provides the resources and support you need to craft compelling stories.

Do you find yourself struggling to define the plot of your story? Are you unsure how to structure your narrative or create compelling conflict? At WHAT.EDU.VN, we understand the challenges writers face.

8.1. Get Your Questions Answered for Free

We offer a platform where you can ask any question about writing, storytelling, or plot development and receive answers from our community of experts. Our services are completely free, providing you with the knowledge and guidance you need to improve your craft.

8.2. Why Choose WHAT.EDU.VN?

- Free Access: Ask unlimited questions and receive expert answers without any cost.

- Fast Responses: Get timely and accurate information to keep your writing process moving forward.

- Knowledgeable Community: Connect with experienced writers and industry professionals.

- Easy to Use: Our platform is designed for simplicity and convenience, making it easy to ask questions and find the answers you need.

8.3. Don’t Let Your Questions Hold You Back

Visit WHAT.EDU.VN today and start asking your questions. Let us help you unlock your storytelling potential and craft narratives that captivate and inspire.

Contact Us:

- Address: 888 Question City Plaza, Seattle, WA 98101, United States

- WhatsApp: +1 (206) 555-7890

- Website: what.edu.vn

Don’t wait any longer—your story is waiting to be told!