For decades, the Pew Research Center has dedicated itself to analyzing public attitudes on crucial issues, identifying variations across different demographic groups. Generational analysis is a key tool they employ to understand these differences.

Generations allow us to examine Americans based on their stage in life – young adulthood, middle age, or retirement – and as members of a cohort born around the same time.

Michael Dimock, former president of Pew Research Center, emphasizing the importance of generational studies in understanding societal shifts.

As highlighted in their previous work, generational cohorts are valuable for researchers tracking shifts in perspectives over time. They provide insights into how formative experiences – including significant global events, technological advancements, and socio-economic changes – interact with aging and life cycles to mold worldviews. While opinions may differ between younger and older individuals at any given moment, generational cohorts enable researchers to study how today’s older adults felt about specific issues when they were younger and to map out potentially diverging opinion trajectories across generations.

Pew Research Center has extensively studied the Millennial generation for over a decade. However, by 2018, it became necessary to establish a clear dividing line between Millennials and the subsequent generation. With the oldest Millennials approaching 38 years old that year, having entered adulthood well before today’s youngest adults were even born, the need for a distinction was clear.

To maintain the analytical relevance of the Millennial generation and to begin examining the unique traits of the next cohort, Pew Research Center decided to set 1996 as the final birth year for Millennials in their ongoing research. Individuals born between 1981 and 1996 (aged 23 to 38 in 2019) are classified as Millennials, while those born from 1997 onwards belong to a new generation.

Online search trends indicating “Generation Z” as the dominant term for the post-Millennial generation, reflecting its widespread adoption in popular culture and media.

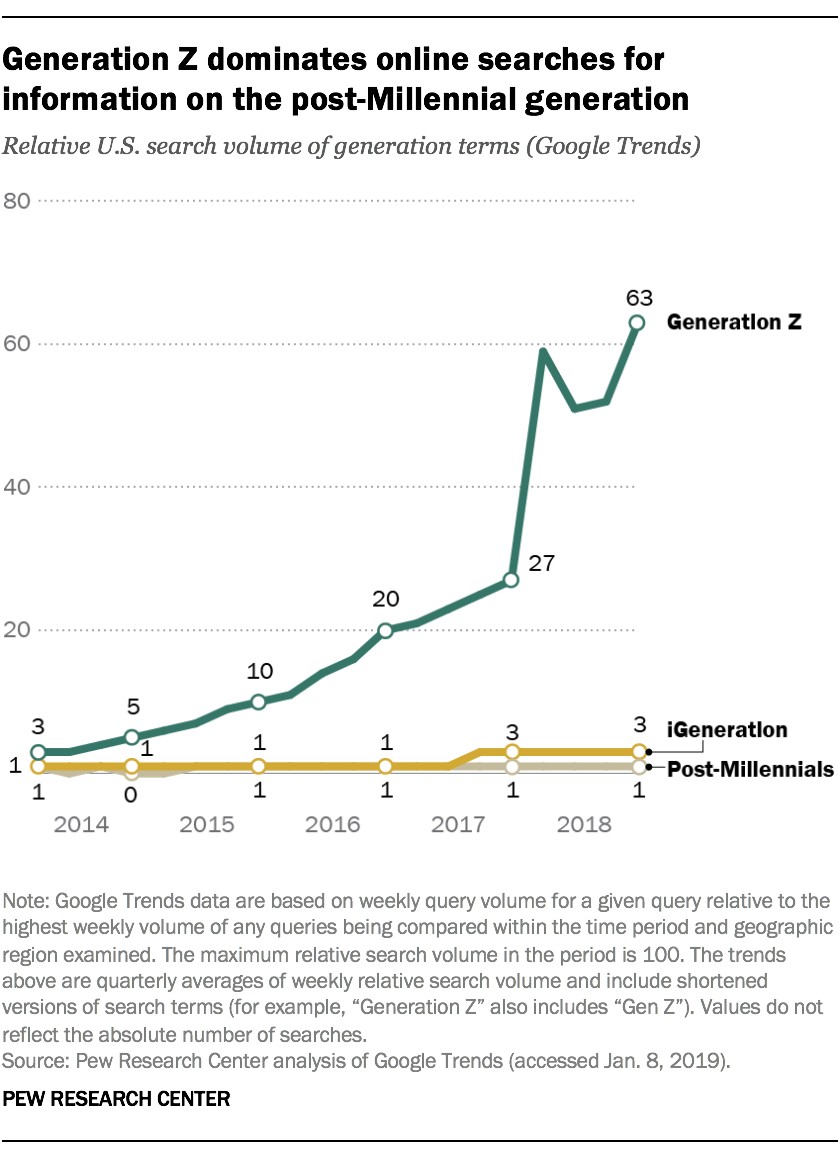

Initially, there was hesitation in naming this rising generation, as the oldest members were only turning 22 in 2019, with most still in their teens or younger. Early contenders included Generation Z, the iGeneration, and Homelanders. (In their initial in-depth analysis of this generation, Pew Research Center used “post-Millennials” as a temporary label.) However, “Gen Z” gained traction in popular culture and journalism. Reputable sources like Merriam-Webster, Oxford, and Urban Dictionary now recognize this term for the generation following Millennials. Google Trends data confirms that “Generation Z” significantly surpasses other names in online searches. While the adoption of a generational name isn’t governed by a scientific process, the momentum is clearly behind Gen Z.

It’s important to remember that generational cutoffs are not precise scientific boundaries. They are primarily analytical tools. While the boundaries are not arbitrary, there isn’t a universally agreed-upon formula for the duration of a generation. Pew Research Center’s working definition of Millennials, spanning 16 years (1981 to 1996), mirrors the age span of Generation X (1965-1980). Both are shorter than the Baby Boomer generation (19 years), the only generation officially recognized by the U.S. Census Bureau, defined by the post-WWII birth surge in 1946 and the subsequent birth rate decline after 1964.

Unlike the Boomers, there are no similarly definitive benchmarks for defining later generational boundaries. However, for analytical purposes, 1996 serves as a meaningful dividing point between Millennials and Gen Z for several reasons, including significant political, economic, and social factors that shaped the Millennial generation’s formative years.

A visual representation of generational spans, highlighting the defined periods for Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z, based on Pew Research Center’s criteria.

Most Millennials were between 5 and 20 years old when the 9/11 terrorist attacks occurred, and many were old enough to grasp the historical impact of that event. In contrast, most Gen Z members have limited or no memory of it. Millennials also grew up during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, which influenced broader political views and contributed to the intense political polarization prevalent today. Furthermore, most Millennials were between 12 and 27 during the 2008 election, where the youth vote’s influence became a significant political narrative, contributing to the election of the first African American president. Millennials are also the most racially and ethnically diverse adult generation in U.S. history, but Generation Z is even more diverse.

Economically, most Millennials entered adulthood and the workforce during the peak of the Great Recession. This recession significantly impacted many of their life choices, future earning potential, and entry into adulthood, potentially differentiating their experiences from younger generations. The long-term consequences of this “slow start” for Millennials will continue to shape American society for decades.

Technology, especially the rapid evolution of communication and interaction methods, is another crucial factor shaping generations. Baby Boomers experienced the dramatic expansion of television, fundamentally altering their lifestyles and global connectivity. Generation X grew up alongside the computer revolution, and Millennials came of age during the internet boom.

What distinguishes Generation Z is that they have lived with all these technological advancements from the beginning. The iPhone launched in 2007, when the oldest Gen Z members were around 10 years old. By their teens, mobile devices, Wi-Fi, and high-bandwidth cellular service became the primary means for young Americans to access the internet. Social media, constant connectivity, and on-demand entertainment and communication are innovations that Millennials adapted to as they matured. For those born after 1996, these are largely taken for granted.

The full impact of growing up in an “always-on” technological environment is just beginning to emerge. Recent research indicates significant shifts in youth behaviors, attitudes, and lifestyles – both positive and concerning – among those who have come of age in this era. However, it remains unclear whether these are lasting generational imprints or simply characteristics of adolescence that will diminish as they age. Tracking this new generation over time is crucial.

Pew Research Center acknowledges that they are not the first to differentiate between Millennials and the subsequent generation, and valid arguments exist for setting the dividing line a few years earlier or later. Future data collection may reveal a clearer, more definitive demarcation. They remain open to adjusting their definition if necessary. However, it’s more likely that historical, technological, behavioral, and attitudinal data will reveal a continuum across generations rather than a sharp threshold. As in the past, differences within generations can be as significant as those between generations, and the youngest and oldest members of a defined cohort may share more common ground with adjacent generations than with their own. This highlights that generations are inherently diverse and complex groups, not simplistic stereotypes.

Looking ahead, Pew Research Center will continue to expand its generational research with numerous reports and analyses. They recently released a report examining Generation Z’s views on key social and political issues and comparing them to older generations. While Gen Z’s perspectives are still developing and subject to change as they mature and as global events unfold, this initial analysis provides valuable early insights into how Gen Z may influence the future political landscape.

In the coming period, demographic analyses will be released comparing Millennials to previous generations at similar life stages to assess whether Millennials’ demographic, economic, and household patterns continue to diverge from their predecessors. Furthermore, they will build upon existing research on teens’ technology use to explore the daily lives, aspirations, and challenges faced by today’s 13- to 17-year-olds as they navigate adolescence.

However, caution is necessary when projecting characteristics onto a generation that is still so young. Donald Trump may be the first U.S. president most Gen Zers remember as they reach adulthood. Just as the contrast between George W. Bush and Barack Obama shaped political discourse for Millennials, the current political environment could similarly influence the attitudes and engagement of Gen Z, although the specific nature of this influence remains to be seen. Despite the perceived importance of current events, the technologies, debates, and events that will truly shape Generation Z are likely yet to emerge.

Pew Research Center is committed to studying this generation as it enters adulthood, remembering that generations are a lens for understanding societal change, not labels for oversimplifying group differences.

Note: This article is updated from a post originally published on March 1, 2018, announcing Pew Research Center’s adoption of 1996 as the cutoff year for the Millennial generation.