The date September 11, 2001, is etched into the memory of millions around the world. What year was 9/11? It was indeed 2001, a year that irrevocably changed the course of American history and global politics. On that fateful day, terrorist attacks in New York City, Washington, D.C., and Shanksville, Pennsylvania, claimed nearly 3,000 lives, leaving an indelible scar on the American psyche. Two decades later, as the United States concluded its military mission in Afghanistan – a mission initiated in the aftermath of 9/11 – the legacy of that day continues to shape public opinion and national discourse.

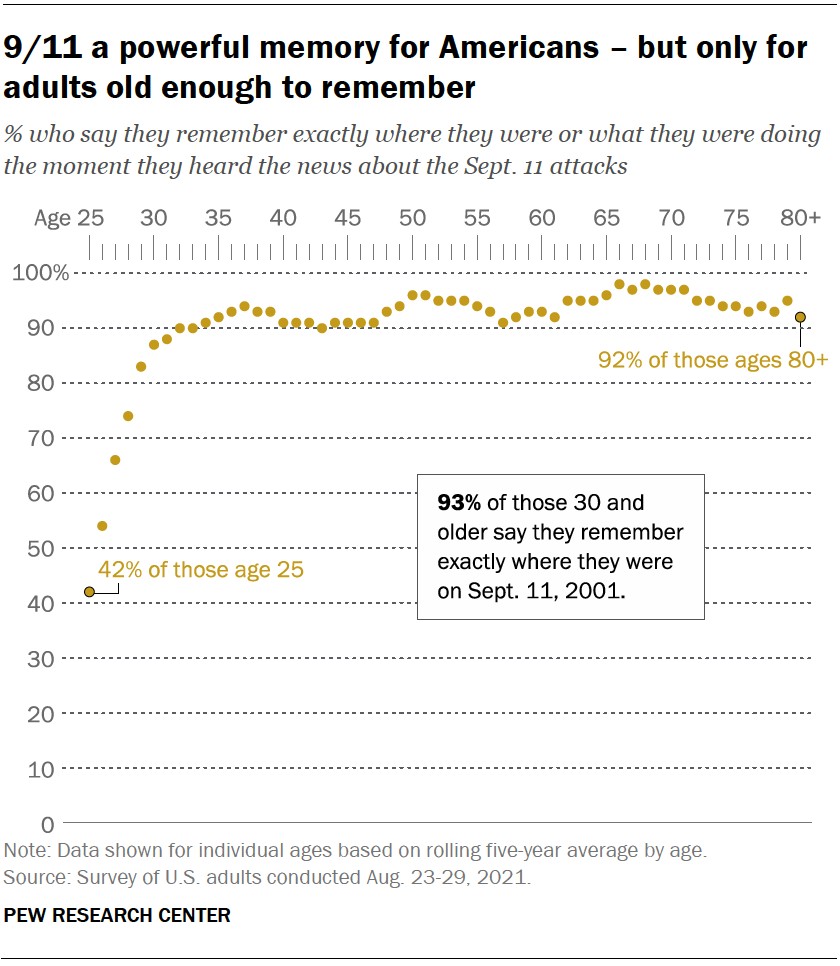

For Americans old enough to remember, September 11, often referred to as 9/11, remains a vivid and poignant memory. The overwhelming majority of adults who were alive at the time can recall exactly where they were and what they were doing when news of the attacks broke. However, a growing segment of the American population, those born after or too young to remember 2001, lacks a personal connection to this pivotal moment in history.

Examining public opinion trends in the twenty years following 9/11 reveals a nation initially united in grief and patriotism. It shows how public support rallied behind military interventions in Afghanistan and Iraq, though this support gradually eroded over time. It also highlights evolving American perceptions of the terrorist threat and government measures to counter it. The recent withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan has prompted critical reflections on American foreign policy and its global role. Public sentiment regarding the Afghanistan mission is clear: while a majority supported withdrawal, the Biden administration’s execution of it faced criticism. After a prolonged war marked by significant human and financial costs, a Pew Research Center survey indicates that 69% of U.S. adults believe the United States largely failed to achieve its objectives in Afghanistan.

The Immediate and Lasting Emotional Scars of 9/11

The 9/11 attacks unleashed a wave of intense emotions across America – shock, sadness, fear, and anger. In the immediate aftermath, a staggering 63% of Americans admitted they were unable to stop watching news coverage of the unfolding tragedy.

A survey conducted just days after the attacks, between September 13-17, 2001, captured the profound psychological impact. A substantial 71% of adults reported feeling depressed, nearly half (49%) struggled with concentration, and a third experienced sleep disturbances. In an era dominated by television as the primary news source – 90% of Americans relied on TV for updates on the attacks, compared to a mere 5% online – the graphic images of destruction were deeply impactful. An overwhelming 92% expressed sadness when watching TV coverage, and while 77% found it frightening, they continued to watch.

Anger was another dominant emotion. Even as the initial shock began to subside three weeks later, 87% of Americans reported feeling angry about the attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. Fear permeated American life throughout the fall of 2001. Most Americans expressed worry about the possibility of further attacks, with 28% feeling very worried and 45% somewhat worried. A year later, when asked about major life changes resulting from 9/11, about half of adults cited increased feelings of fear, caution, distrust, or vulnerability.

Concerns about terrorism were particularly heightened in major cities, especially New York and Washington D.C., compared to smaller towns and rural areas. The personal impact was more acutely felt in the targeted cities. Nearly a year after 9/11, approximately six-in-ten adults in New York (61%) and Washington (63%) reported that the attacks had changed their lives at least to some extent, compared to 49% nationwide. This sentiment resonated in other large urban centers as well. A quarter of big city residents nationwide felt their lives had changed significantly, double the rate in small towns and rural areas.

The repercussions of 9/11 were deeply ingrained and slow to fade. By the following August, half of U.S. adults believed the country had undergone a “major change,” a figure that actually increased to 61% a decade later, 10 years after the event. In an open-ended question a year after the attacks, 80% of Americans identified 9/11 as the most significant national event of the preceding year. Remarkably, a larger proportion even cited it as the most important personal event of the year (38%) compared to typical life events like births or deaths. Again, the personal impact was even more pronounced in New York and Washington, D.C., where 51% and 44%, respectively, considered the attacks their most significant personal event of the past year.

Memories of 9/11 are deeply entrenched in the minds of Americans who lived through the attacks, and its historical significance surpasses other events in their lifetimes. In a 2016 Pew Research Center survey conducted in collaboration with A+E Networks’ HISTORY, 76% of adults named the September 11 attacks as one of the 10 historical events of their lifetime with the greatest impact on the United States. The election of Barack Obama, the first Black president, ranked second at 40%. The significance of 9/11 transcended demographic and political divides. The 2016 study revealed that, despite partisan polarization on many issues during that election cycle, over 70% of both Republicans and Democrats included the attacks among their top 10 historic events.

The Transformative but Fleeting Impact of 9/11 on U.S. Public Opinion

The 9/11 attacks were a watershed moment, profoundly reshaping U.S. public opinion across numerous dimensions. Beyond the shared grief, the months following September 11th were characterized by an unusual sense of national unity.

Patriotism surged in the aftermath of 9/11. Following U.S.-led airstrikes against Taliban and al-Qaida forces in October 2001, 79% of adults reported displaying an American flag. A year later, 62% said they frequently felt patriotic as a result of the attacks. Political divisions diminished as the public largely united behind national institutions and political leadership. In October 2001, 60% of adults expressed trust in the federal government – a level unseen in the preceding three decades and unmatched in the two decades since.

President George W. Bush, who had assumed office just nine months prior after a highly contested election, witnessed a remarkable 35-percentage-point surge in job approval within three weeks. By late September 2001, 86% of adults, including nearly all Republicans (96%) and a significant majority of Democrats (78%), approved of Bush’s presidential performance. Americans also turned to religion and faith in large numbers. In the days and weeks following 9/11, many reported praying more often. In November 2001, 78% believed religion’s influence in American life was growing, more than double the percentage eight months earlier and, mirroring public trust in government, the highest level in four decades.

Public regard even increased for institutions often viewed with skepticism. For instance, news organizations received record-high professionalism ratings in November 2001. Approximately 69% of adults felt they “stand up for America,” and 60% believed they protected democracy. However, the “9/11 effect” on public opinion proved largely transient. Public trust in government and confidence in other institutions declined throughout the 2000s. By 2005, following the government’s widely criticized response to Hurricane Katrina, only 31% expressed trust in the federal government, half the proportion in the months after 9/11. This low level of trust has persisted for the last two decades: In April of this year, just 24% indicated they trusted the government always or most of the time. Bush’s approval ratings also never regained their post-9/11 peak. By the end of his presidency in December 2008, only 24% approved of his job performance.

U.S. Military Response: Afghanistan and Iraq

With the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan complete and the Taliban regaining control, a majority of Americans (69%) believe the U.S. failed to achieve its objectives in Afghanistan.

However, in the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Americans overwhelmingly supported military action against those responsible. In mid-September 2001, 77% favored U.S. military action, including ground troop deployment, “to retaliate against whoever is responsible for the terrorist attacks, even if that means U.S. armed forces might suffer thousands of casualties.” Many Americans were eager for swift military action. In a late September 2001 survey, 49% expressed greater concern that the Bush administration would not act quickly enough against terrorists, while only 34% worried about overly hasty action. Even early on, few anticipated a quick military resolution. A substantial 69% believed dismantling terrorist networks would take months or years, with 38% estimating years and 31% several months. Only 18% expected it to take days or weeks.

Public support for military intervention was also evident in the preference for military action abroad over domestic defense buildup as the best counter-terrorism strategy. In early October 2001, 45% prioritized military action to dismantle terrorist networks globally, while 36% favored strengthening domestic terrorism defenses.

Initially, there was strong public confidence in the success of U.S. military efforts against terrorist networks. A significant 76% were confident in this mission’s success, with 39% expressing strong confidence. Support for the war in Afghanistan remained high for several years. In early 2002, months after the war’s commencement, 83% approved of the U.S.-led military campaign against the Taliban and al-Qaida in Afghanistan. In 2006, several years into combat operations, 69% of adults still believed the U.S. made the right decision to use military force in Afghanistan, with only 20% dissenting.

However, as the conflict prolonged through the Bush and Obama administrations, support waned, and a growing number of Americans favored troop withdrawal. In June 2009, during Obama’s first year, 38% advocated for immediate troop removal. This percentage increased in subsequent years. A turning point occurred in May 2011 with the U.S. Navy SEALs operation that killed Osama bin Laden in Pakistan. Public reaction to bin Laden’s death was more relief than jubilation. A month later, for the first time, a majority (56%) favored immediate troop withdrawal, while 39% preferred troops to remain until stabilization.

Over the next decade, U.S. troop levels in Afghanistan gradually decreased across the Obama, Trump, and Biden administrations. Public support for military intervention in Afghanistan, once widespread, declined. Currently, following the chaotic withdrawal, a narrow majority (54%) considers the withdrawal decision correct, while 42% disagree. A similar trend emerged regarding the U.S. war in Iraq, another component of Bush’s “war on terror.” Despite contentious debate preceding the 2003 invasion, Americans largely supported military action to remove Saddam Hussein. Crucially, a majority incorrectly believed in a direct link between Saddam Hussein and the 9/11 attacks. In October 2002, 66% believed Saddam aided the 9/11 terrorists.

In April 2003, during the Iraq War’s initial month, 71% deemed the war decision correct. However, by its 15th anniversary in 2018, only 43% still considered it the right decision. Similar to Afghanistan, more Americans believed the U.S. had failed (53%) rather than succeeded (39%) in achieving its Iraq war goals.

The “New Normal”: The Enduring Threat of Terrorism After 9/11

While no terrorist attacks on the scale of 9/11 have occurred in the subsequent two decades, the public perception of a persistent threat remains. Since 2002, defending against future terrorist attacks has consistently ranked as a top policy priority in Pew Research Center’s annual surveys.

Since January 2002, just months after the 2001 attacks, 83% of Americans ranked “defending the country from future terrorist attacks” as a top priority for the president and Congress, the highest among all issues. Large majorities have continued to prioritize this issue since then. Both Republicans and Democrats have consistently viewed terrorism as a top priority over the past two decades, although Republicans and Republican-leaning independents have been consistently more likely than Democrats and Democratic leaners to prioritize it. In recent years, this partisan gap has widened as Democrats have begun to prioritize it lower relative to domestic concerns.

Public concern about further attacks remained fairly stable in the years after 9/11, despite near-misses and numerous “Orange Alerts.” A 2010 analysis found that the proportion of Americans “very concerned” about another attack fluctuated between 15% and 25% since 2002. The only period of heightened concern was February 2003, preceding the Iraq War. In recent years, terrorism as a major national problem has declined in public perception, as issues such as the economy, the COVID-19 pandemic, and racism have risen in prominence.

In 2016, 53% of the public considered terrorism a very big national problem. This decreased to around 40% between 2017 and 2019. Last year, only a quarter of Americans viewed terrorism as a very big problem. This year, before the Afghanistan withdrawal and Taliban takeover, a slightly larger proportion considered domestic terrorism a very big national problem (35%) than international terrorism. However, issues like healthcare affordability (56%) and the federal budget deficit (49%) were cited as major problems by larger segments of the public than either domestic or international terrorism. Nevertheless, recent events in Afghanistan suggest public opinion on terrorism could be shifting, at least in the short term. In a late August survey, 89% of Americans considered the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan a threat to U.S. security, with 46% viewing it as a major threat.

Balancing Security and Civil Liberties in the Post-9/11 Era

Just as Americans largely supported military action after 9/11, they initially accepted a range of extensive measures to combat terrorism domestically and internationally. In the days following the attacks, majorities favored measures like national ID cards for all citizens, CIA contracts with criminals for pursuing suspected terrorists, and CIA assassinations of suspected terrorists overseas.

However, public support had limits. Most opposed government monitoring of personal emails and phone calls (77%). And while 29% supported internment camps for legal immigrants from unfriendly nations during crises – reminiscent of the Japanese American internment during World War II – 57% opposed this. Public perception of the balance between civil liberties and national security shifted significantly. In September 2001 and January 2002, 55% majorities agreed that some civil liberties needed to be sacrificed to curb terrorism. In 1997, only 29% held this view, while 62% disagreed. For much of the subsequent two decades, more Americans worried that the government had not gone far enough in protecting against terrorism than that it had gone too far in restricting civil liberties. The public also did not dismiss the use of torture to extract information from terrorist suspects. A 2015 survey across 40 nations revealed that the U.S. was among only 12 where a majority considered torture justifiable to gain information about potential attacks.

Increased Partisan Divide in Views of Muslims and Islam Post-9/11

In the aftermath of 9/11, amid concerns about potential backlash against Muslims in the U.S., President George W. Bush delivered a speech at the Islamic Center in Washington, D.C., declaring, “Islam is peace.” For a brief period, a significant portion of Americans concurred. In November 2001, 59% of U.S. adults held a favorable view of Muslim Americans, up from 45% in March 2001, with similar majorities across party lines expressing positive opinions.

This unity was short-lived. A September 2001 survey showed 28% of adults reporting increased suspicion of people of Middle Eastern descent, rising to 36% within a year. Republicans, in particular, increasingly linked Muslims and Islam with violence. In 2002, 25% of Americans, including 32% of Republicans and 23% of Democrats, believed Islam was more prone to encourage violence than other religions. Approximately twice as many (51%) disagreed. However, within a few years, most Republicans and GOP leaners believed Islam was more likely to encourage violence. Currently, 72% of Republicans hold this view, according to an August 2021 survey. Democrats have consistently been less likely than Republicans to associate Islam with violence. In the latest survey, 32% of Democrats hold this view. However, this is a slight increase from 2019, when 28% of Democrats expressed this belief.

The partisan divide in views of Muslims and Islam in the U.S. is further evident. A 2017 survey found that half of U.S. adults believed “Islam is not part of mainstream American society,” a view held by nearly 70% of Republicans (68%) but only 37% of Democrats. In a separate 2017 survey, 56% of Republicans perceived significant extremism among U.S. Muslims, compared to less than half as many Democrats (22%). The rise of anti-Muslim sentiment after 9/11 has profoundly impacted the growing Muslim population in the United States. Surveys of U.S. Muslims from 2007-2017 revealed increasing reports of personal discrimination and public expressions of support.

Two decades have passed since the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon, and the crash of Flight 93. For those who remember, September 11, 2001, remains an unforgettable day. It fundamentally reshaped American perspectives on war, peace, personal safety, and national identity. The recent turmoil in Afghanistan marks the beginning of a new, uncertain chapter in the post-9/11 era.